Mary did not speak to Winn again that morning but she was conscious of his presence at the plot. He shuffled out of his office three, perhaps four times, to stand beside it, stroking his cheek thoughtfully, cigarette burning between his fingers. After an unpleasant lunch in the Admiralty canteen, she returned to her desk to find a note from him in her in-tray.

An interrogator from Section 11 visiting tomorrow at 1100. He says he has something for us. Talk to him.

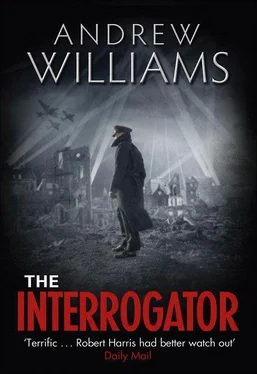

Mary groaned and glanced resentfully at Winn’s office but he was out. She pushed the note away. Who was this interrogator and what was so important that he could not send in a report like the rest of his Section?

MI5 Holding Centre

Camp 020

Ham Common

London

There was a sharp grating noise on the flagstones and the interrogator’s head bobbed out of the light. He had lost patience. On the other side of the desk Helmut Lange hunched his shoulders. His right knee was trembling and his mouth was sticky dry. This time the blow drove him to the floor, a crushing tide of pain breaking through his body. The room was hot with confused, brilliant light. Something was dripping on to the stone in front of him.

‘Get up. Get up.’

The words seemed to echo down a long tunnel. Then someone grabbed his arm tightly, pulling him to his feet.

‘I know you’re a spy, Leutnant Lange. Help me and you will help yourself.’ Lange could feel the interrogator’s breath on his cheek, smoky stale. He was an elderly man, softly spoken and with strangely sympathetic eyes, an army officer of some kind. His German was thickly accented. There were two more soldiers in the room, younger, harder.

‘I’m a navy journalist,’ Lange croaked, ‘I’ve told you. It was my first war patrol.’ His lips were salty with blood.

‘The U-500 was going to land you in Scotland. Who were you to contact?’

Lange tried to shake his head. Shapes swirled before his eyes: highly polished shoes, well-creased trousers — someone was wearing gloves — crimson spots, there were drops of blood on his prison overalls. He felt guilty about the blood.

‘You speak English,’ said the interrogator.

‘A little,’ groaned Lange.

‘And you’ve been trained to use a wireless transmitter.’

‘No.’

‘You’re not the first, Herr Lange. We were expecting you. Another of Major Ritter’s men. You were trained in Hamburg?’ There was a note of quiet menace in the interrogator’s voice.

‘I was writing a feature piece,’ said Lange. ‘Why won’t you believe me? Please, please ask the crew. Ask the commander, he’ll tell you.’

‘You’re a fool not a hero, Herr Lange, and we’re losing patience with you.’ The interrogator paused, then added in almost a whisper: ‘If you won’t co-operate we’ll take you to Cell Fourteen. The mortuary is opposite Cell Fourteen.’

Lange knew he couldn’t stand any more, but how could he make them believe him? He had been in the room for hours, the same questions over and over, questions he could not answer. He knew nothing of U-boats or spies. It had been his first war patrol.

And then he was on his knees again, gasping for air, a deep throbbing pain in his side. He was going to be sick. One of the other men was shouting at him now: ‘Cell Fourteen, Lange, Cell Fourteen… oh Christ he’s…’

There was a bitter taste of bile in Lange’s mouth. He retched again. His knees felt wet. The interrogator said something in English he could not understand. Then shadows began to move across the floor.

The door opened and he heard the sharp click of leather-soled shoes. Were they taking him to Cell Fourteen? He felt dizzy and he was shaking. There was a murmur in the room, his interrogator’s voice raised sharply above the rest. They were arguing. Lange caught no more of their conversation than his name. It was important not to speak or move. He felt so tired, tired enough to fall asleep there on the floor.

For a moment, he thought he had been struck again. The room was full of painful light. But a soft voice he did not recognise said in perfect German,‘You can get up now, Herr Leutnant.’

He was suddenly conscious that he was kneeling in a pool of vomit. There were five men in the room and they were all looking at him. He felt no better than a dog, broken and humiliated. He lifted a trembling hand to his swollen face. One of his eyes had closed.

‘Let me help you.’ It was the same calm, reassuring voice and instead of khaki this man was wearing the blue uniform of a naval officer. Lange began to cry quiet tears of shame. The naval officer reached down and hoisted him up on to unsteady legs.

‘My name is Lieutenant Lindsay. I want you to come with me.’

Confused, Lange followed him out of the interrogation room and slowly, head bowed, along a dark corridor with cell doors to left and right. Footfalls echoed behind them and his heart beat faster. Perhaps it was a trick and they were going to drag him back. But at the end of the corridor, a guard opened the steel security gate and Lindsay led him down a short flight of steps into the rain. He stood in front of the cell block, cool drops falling gently on his face. Smoky London rain, he could taste it, smell it. To his right there was a large yellow-brick Victorian villa; opposite, a collection of Nissan huts and the perimeter wire. A wooden screen had been built a few yards beyond it to shield the camp from passers-by.

‘Where is this place?’

‘Do you smoke?’ Lieutenant Lindsay offered him a silver cigarette case. Lange tried to take one but his hand was still shaking uncontrollably. ‘Here.’ Lindsay held a cigarette to his lips. The smoke made him giddy, numbing the pain in his face and sides.

Lindsay waved to a large black official-looking car that was parked in front of the house. It moved forward at once and a few seconds later pulled up in front of the cell block. The soldier behind the wheel stepped smartly out and opened the rear doors. Lange shuffled across the red leather seat, his trousers clinging unpleasantly to his knees.

‘I’m sorry,’ he muttered, conscious of the sickly-sweet smell.

The heater was on and the air was hot and stale. An opaque glass screen separated them from the driver and blinds were pulled down over the rear windows. It looked and felt like a funeral car. The engine turned again. Lange glanced across at the British officer sitting impassively beside him, and wiped his eyes with the back of his hand. He wanted to say, ‘Thank you, thank you for saving me,’ but the tight anxiety of the last four days was draining from him and his head began to nod forwards. He was just conscious of stammering, ‘Where are we going?’ but if there was an answer he did not hear it.

Room 41

The Citadel

London

It was a little after eleven and Mary Henderson had just begun to hack her way through a report from the Admiralty’s technical branch when a shadow fell across her desk. She raised her eyes to its edge, to the doeskin sleeves and gold hoops of a reserve lieutenant.

‘This is Dr Henderson.’ Rodger Winn was standing at his side. ‘Mary, I would like you to meet one of our colleagues from Section 11.’

The interrogator; she had forgotten all about him. She pushed her chair back and looked up at a curiously striking face, thin, with prominent cheek-bones and a nose that looked as if it had been broken on the rugby field. The lieutenant was at least six feet tall, upright, with wavy fair hair, youthful but for the dark shadows about his blue eyes.

Читать дальше