‘Get that fuckin’ door open now, you lazy lummox,’ Duncan bellowed, bank manager no longer but shipyard keelie. ‘And put your back into it. Oh God, give it here,’ and he snatched the sledgehammer from the soldier. Swinging his broad shoulders, he brought it down with such force that the lock burst, oak splintering, the hammer bouncing from his hands. It was as if a great cathedral bell had sounded only feet away. Only Duncan had enough presence to act, throwing his shoulder against the door: ‘You after an invitation?’

It gave way and he stumbled headfirst into the washroom. Lindsay followed, the soldiers at his back.

‘Stop it or we’ll shoot.’

He could see Lange’s twisted face and the rope in the light from a high washroom window. His body was shaking, his mouth open, gasping, gasping for air. But he was heavy and they were trying to lift his legs to tighten the rope. There were five, perhaps six men. Was that Dietrich?

‘Stop it now or I’ll shoot. Now.’

Dietrich turned to shout something to the others and they stepped back, their hands in the air. And now Lange was swinging, the rope creaking, taut, twisting, swinging free, a strange gurgling noise in his throat and his chest heaving for air. And Lindsay grabbed him and held his knees: ‘For God’s sake help me.’

Then a sharp crack above his head and a drenching spout of water and Lange’s body slipped from the broken pipe. Hands helped to ease it to the wet stone floor. Strings of hair across his forehead, eyes half closed, and the water drumming against Lindsay’s back as he bent to shelter him from its force.

‘Please God… a doctor, a doctor now.’

The cold was seeping through his jacket and through his shirt and creeping through his body. What had he done? Lange was dead.

A single bad deed by one individual can jeopardise the achievements of many others. The favourable reputation of an entire fighter group can be wiped out by some foolish or unnecessary act of violence by only one of its members. This lapse of common sense actually gives aid to the enemy, who will exploit the misdeed… the guilty conscience alone will perform most of the work advantageous to the inquisitor.

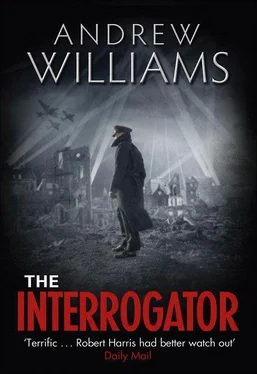

Hanns Joachim Scharff, Interrogator, Luftwaffe Interrogation Centre, Oberursel, Germany, 1943–45 Raymond F. Tolliver,

The Interrogator: The Story of Hanns Joachim Scharff, Master Interrogator of the Luftwaffe

18:30

13 September

Brixton Prison

London

The police van was careering through the streets at dusk like something from a Hollywood gangster picture. A railway arch, the broken front of a chemist’s, sooty houses and the shell of a large department store, south London flashing by the small square grille in the rear door like images in a Rotoscope. And Mohr sliding about the seat handcuffed to a policeman who was clutching a helmet to his lap. It might have been comic but it was just demeaning. A large but simple church with fluted columns, more houses, then a sharp turn right to the gates and white stone towers of what could only be a prison.

‘Where is this?’

The policeman glanced at him, then down at his helmet. The gates swung open on to yellow-black walls, a curious octagonal building flanked on either side by the four-storey wings of the prison. And it was here, in front of Prisoner Reception, that the van came to a halt.

‘Strip.’

How had it come to this? To be treated like a criminal. He had fallen into a dark place.

‘I am a naval officer.’

‘Scales.’

Something was eating at his core, the loss of the boat, captivity, it was impossible to be quite sure, but he felt emptier and more uncertain. He had made mistakes.

‘Uniform.’

Someone thrust a rough khaki shirt and trousers into his arms. There was a dark stain on the front of the shirt and the trousers were too large at the waist. One of the warders was turning Mohr’s white cap over in his hands, then with a sly smile he placed it on the table and began prising the badge from the band.

‘F’ Wing at Brixton clattered like an empty dustbin. British fascists and Irish nationalists, spies and murderers, their shouts and groans in the night, their boots on the stairs and the landings, the rattle of keys in security gates and the heavy slamming of doors. A Victorian hell of steel and bare brick and chipped and dirty whitewash. His cell was four metres by two, a barred window high in the wall, a bucket and a bed. That night as he lay on his thin damp mattress, the cold echo of the prison shackling his mind, Mohr knew he was a prisoner in a way he had not been before.

At slopping-out the next morning he saw Dietrich and Schmidt further down the landing in the same prison browns, heads bent over their shit. And he felt a contempt for their stupidity that was matched only by the contempt he felt for himself. Then at eleven o’clock there were footsteps and voices outside his cell and someone pressed an eye to the slot in the door. A moment later it opened and Lindsay stood there, a prison warder at his back.

‘I’ve brought you a newspaper,’ he said in English and tossed the Daily Mail on to the bed. ‘Now you’re a celebrity here too.’

Mohr looked at it for a moment, then picked it up and opened it on his knee. His own picture was at the bottom of the front page beneath the latest news of the war in the Soviet Union. It must have been taken in Liverpool when the crew was escorted off the ship. And the bold headline beneath it:

U-boat Commander to be Charged with Murder

He flinched and closed his eyes for a moment as if someone had caught him hard in the stomach. It was public knowledge, perhaps in Germany too. Humiliating. The copy beneath the picture said that a man had been ‘brutally’ murdered at a camp for enemy officers in the north of England. A number of German prisoners were being held, including a ‘senior Nazi U-boat Commander’ and it mentioned him by name. And he was also to be ‘charged’ with conducting an ‘illegal court-martial hearing’.

Mohr looked sideways at Lindsay: ‘Have you read this?’

‘Of course.’

‘… this ruthless Nazi officer is responsible for the deaths of many British seamen and now with equal ruthlessness he has turned against one of his own …’ Who is this person?’

‘You, Mohr, you,’ said Lindsay contemptuously. ‘You will be brought before a court in the next few days. You and your lynch mob: Dietrich and Bruns and Schmidt and Koch and the others too. You will be found guilty and hanged.’

‘You are the one who should be in court.’ Mohr’s voice shook with repressed fury.

Why had Lindsay done this to him? He was going to dress it up as a dirty little crime, Mohr the murderer, the mindless Nazi thug. It was more than just an intelligence trick, it felt personal in some way, an assault on his integrity, his reputation. But he was caught, a fly in a web.

He tried to collect himself: ‘No one has taken a statement from me.’

‘You look worried. We don’t need a statement. We have witnesses. I heard you myself.’

‘I want to give a statement.’

Lindsay shook his head, then; half turning to the prison warder behind him, said: ‘Look after him. I don’t want to give him the opportunity to make a complaint about his treatment to the court.’

The warder nodded.

Lindsay had reached the door and was on the point of closing it when he turned to look at Mohr again. There was something close to a sneer on his face: ‘I would feel sorry for you but I saw Lange swinging there. The crimes of one man can bring dishonour to many. To think that man would be you, a hero of the Reich.’

Читать дальше