He had been five hours late into Lime Street, the platforms lined with ‘trekkers’, the anxious and the homeless waiting for trains to carry them to the safety of draughty church halls in the suburbs. By the time Lindsay had fought his way out of the station it was after six o’clock. But he was pleased he had missed the White ’s quayside welcome, the little triumph orchestrated for the newsreel cameras. The hacks would have been given their instructions. Mohr was certainly a catch. A celebrity commander never out of the papers, a holder of Germany’s highest decoration — the Knight’s Cross — famous for his dash and style, or what passed for it in the Reich.

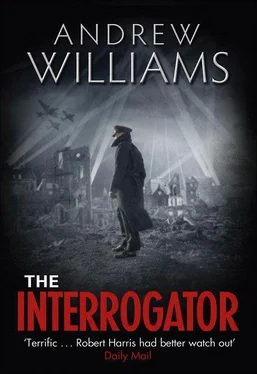

From the west, the distant drone of approaching aircraft, slow and heavy. Searchlights began to sweep in sinister arcs above him and soon the horizon was peppered with the smoky flash of anti-aircraft shrapnel. He stood and watched as if in a dream. The first enemy flares were dripping on to the rooftops of the city, followed moments later by what sounded like a rattle of iron bedsteads thrown from a great height. There was a flash and a tongue of flame — incendiaries.

Then he heard someone shouting at him from across the street.

‘What’s the matter with you…?’ The man’s words were lost in a rising scream.

Lindsay instinctively hunched his shoulders. His feet were knocked from under him and his mouth was full of dirt. He looked up. A policeman was gesticulating wildly: ‘Run you bloody fool.’ Suddenly aware of the mad danger he had placed himself in, he covered the distance to the shelter at breakneck speed. He was just feet from the entrance when the ground rose, throwing him forwards against the sandbags. For a moment everything was a blur. Then someone was pulling his arm, dragging him down rubble-strewn steps towards the door.

‘It’s all right,’ he shouted as he scrambled to his feet.

The door clanged shut behind him.

By the half lantern-light he could see a score or more of frightened faces. His rescuer was shouting something but it was impossible to hear above the scream and crump of bombs. He collapsed on to a bench and rested his chin in his hands. The air was thick with dust and the shelter shook and heaved, the explosions reverberating along its length like a blow on a tremendous kettledrum. The bedlam continued for eight or nine minutes then lifted almost at once. Nobody moved, but the darkness was full of whispering voices and the whimpering of small children.

‘That’s just the start — take my word for it…’ Lindsay’s rescuer had leant across and touched his knee. He looked as if he was in his fifties although it was difficult to tell because his round, amiable face was caked in dust.

‘You were lucky, weren’t cha?’ he wheezed with a scouse accent you could cut with a knife. ‘Feckin death wish…’

‘You can stop that, George Barnes.’ A blowsy-looking woman in a fake-fur wrap elbowed George so hard he nearly toppled off the bench: ‘Just mind your language — there are ladies and children in here.’

The shelter smelt of piss. Some of the children were being settled under blankets on the floor; everyone else was preparing to make the best of the narrow benches for another night. Bundled and patched-up people, smart alecks and quiet ones, some knitting, some playing cards. The bombs were still falling. Like a storm on a distant shore, the low rumble of high explosives seemed to break and retreat. From time to time one fell close enough to send a shudder through the shelter and everyone held their breath and wondered where the next would fall. Then the weary murmur would begin again as if no one in the shelter wanted to be left with their thoughts for long. One of Lindsay’s neighbours, the large woman with the sharp elbows, began to work her way through the streets that had been hit:

‘Fountains Road, Chancel Street, Endborne Road and Newman Street. The shelter was destroyed in Newman Street and three small children from the same family were killed. My cousin Gertrude’s husband was badly hurt on fire-watch down at the docks…’

A wizened old man swaddled in a khaki greatcoat many sizes too big for him leant across the shelter and spoke to Lindsay:

‘My son’s in the Navy. On a battleship.’

Lindsay nodded.

‘Just a rating. Your ship an escort? We’ve got lots of ’em ’ere.’

‘My old ship was a destroyer.’

‘Did you sink one of their submarines?’

‘No,’ said Lindsay.

‘Shame. I hate ’em you know, hate ’em. Don’t you?’

‘Who?’

‘Who d’yer think? Germans. Nazis. Fuckin’ hate ’em.’ The old man spoke in staccato bursts as if he was in danger of being overwhelmed by his own anger. ‘Look at this — women and children. It’s murder. There’s a German lives near us, his name’s Fetteroll. Says he doesn’t want to fight because his father’s German. Don’t understand why they haven’t locked him up in that camp at Huyton with the other Krauts. Shoot the bastard.’ The old man gave a short gasp. There were tears on his face. He wiped them away with the back of his hand. It was some time before he spoke again and then in little more than a whisper.

‘Sorry. Things get on top of you don’t they? You know, my wife…’ He left the sentence hanging there uncertainly and slumped back against the wall of the shelter, lost again in his coat and his misery.

Lindsay tried to think of Mary Henderson. He had seen her twice since the party, a few hours snatched from Naval Intelligence here and there. They had spoken with the same warm frankness, a frankness entirely natural to her but a little foreign to him. There had been other women before, drunken encounters of the sort familiar to most sailors, and two brittle affairs with ‘nice’ west-of-Scotland girls, but never a meeting of sympathetic minds. Mary was challenging, he loved her bright intelligence, her cool expectant eyes, her smile, her strange gasping laugh, and he loved the joy, the hope, he felt when he was with her. There was a sort of stillness, a grace, in Mary that was wholly captivating. Her world was built on sure foundations, faith its cornerstone, unshaken by war. He envied her a little and with her, his life seemed less empty.

The rude clatter of hobnailed boots on the steps dragged Lindsay back to the rumbling, shuddering world of the shelter. The door opened, the blackout curtain was brushed aside and a small boy in pyjamas and a coat was gently propelled across the threshold. He was followed by a burly fireman with a smoke-stained face: ‘Room for one more? Found this little bugger in the street on his own.’

There was a good deal of clucking and fussing as the boy was settled with a blanket and a biscuit. Someone handed the fireman a canteen of water and he emptied it without pausing for breath.

‘What’s it like out there?’ asked Lindsay’s rescuer, George Barnes.

The fireman wiped his chin with a dusty sleeve: ‘The city’s on fire. Hell, that’s what it’s like, hell.’ He seemed remarkably cheerful for one who had just escaped from the other side. ‘Lewis’s Store, Kelly’s and Blackler’s — a couple of the Navy’s ships are on fire, I was on my way there…’

On an impulse, Lindsay got to his feet: ‘I’ll come with you.’

The fireman turned to look him up and down. ‘Why? You’d best leave well alone.’

‘I don’t want to sit here. Let’s go.’ He pushed past the fireman to the door and stepped through it into a strange flickering half-light. The sky was the colour of a blood orange and smoke was rising thickly as far as the eye could see. He could feel the heat on his face and hands and small pieces of burnt paper swirled about him like leaves on an autumn day. A gas main had been hit and a jet of yellow flame was rising from the pavement like a geyser. At the end of the street, a four-storey building was burning fiercely and on the road in front, half buried by bricks and charred timber, a naked body, stiff and white. It was a sickening sight. Lindsay could not tear his eyes away. He took an uncertain step closer and relief began to wash through him: it was a dummy, just a shop’s dummy.

Читать дальше