“Tally is right,” Tucker said with feeling. “We dogs must be ever-vigilant around humans. Age is no factor. Adults are as vulnerable as children. Good eyes. Bad noses. So-so ears. Can’t run worth a damn. Living with a human is a full-time responsibility.”

“You all do a good job,” Sneaky said soothingly.

Pewter raised an eyebrow but kept her mouth shut.

“You can’t pick a mutt, really, Sneaky,” Tally said, showing a touch of Virginia blood snobbery.

“You’d better never say that publicly!” the tiger warned. “This whole country is made up of mutts. You just button that thought right up.”

“What are you talking about?” snapped Tally. “Humans are mutts. They’re mixed up worse than a dog’s breakfast.”

Sneaky replied, “A mutt is a mix of blood, usually smart and strong. Anyway, most Americans like to think that when they think of themselves—you know, the old melting-pot stuff?”

“Surely they can’t believe that.” Tally remained unconvinced.

“Tally, Pewter, and I are mutts,” said Sneaky. “I don’t know my bloodlines.” The tiger cat watched a house light switch on far away in the darkness of the country.

“Speak for yourself,” said Pewter. “I am descended from a Bolling.” Pewter momentarily got all grand, naming an early Virginia family. Robert Bolling of Chellowe was granted a charter for viniculture to grow grapes in the Colony. That was long, long ago.

Knowing better than to argue ancestry, Sneaky demurred, “A formidable family. Robert Bolling used Jefferson as a lawyer when he was right out of law school. Our C.O. was just talking about that with one of her friends.”

“I also have a splash of Venable blood,” Pewter bragged.

Venable, like Valentine, was a Virginia surname with some punch.

Sneaky bit her tongue because she wanted to say “So do hundreds of thousands of Americans by now.” That would have started another fight, and things had been quiet in the truck.

The truck stopped at the gate to Monticello. After they were waved through and they parked, they climbed the hill to the house of the director, Leslie Bowman, and her husband, Courtland Neuhoff. Dogs, horses, and one beautiful daughter completed the picture of a tranquil existence on Jefferson’s mountain.

“I’m leaving the windows open, but you all stay here. You know the drill.” The C.O. closed the driver’s door and walked to her meeting.

Tally hung out the window.

“Get back in here!” Sneaky hissed. “She always turns around, and then she’ll come back and run the windows up within an inch of the top. We have important work to do.”

The dog slunk down, crouched beneath the steering wheel. “She can’t see me now.”

The two cats observed intently as their human walked toward the house. “Okay, she’s in.”

Pewter was already halfway out the window.

“I’ll open the door,” said the tiger cat. “That’s easier than you dogs trying to climb out the window.” Sneaky pressed on the door lever as the dogs leaned against it. It opened just enough for them to drop down to the running board. Freedom!

The tiger cat followed. “No noise,” she ordered.

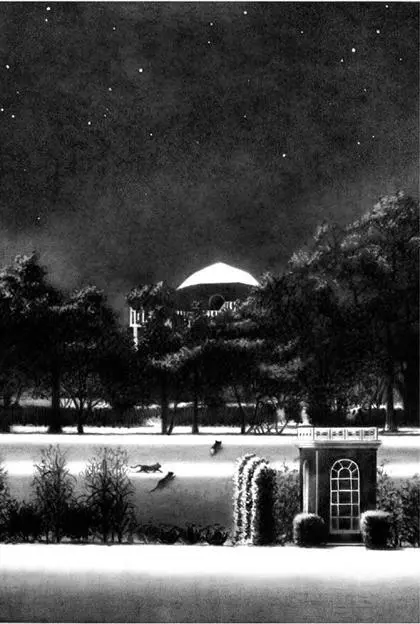

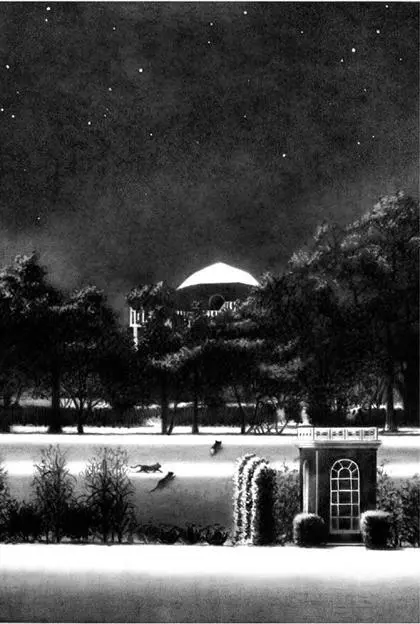

The four animals trotted up the hill toward Monticello, moonlight enshrouding the well-beloved house.

Hovering like an upturned half moon, the signature dome gleamed silver. Early May air carried intoxicating smells from the vegetable garden, as well as the flowers surrounding the back of the house. The roses alone sent off aromas like Eden itself. The drone of insects was subdued, the occasional owl call echoed over the abandoned house. No matter how much a national treasure it was, no house is alive without cats, dogs, people, children playing, fighting, loving—just breathing within its walls.

The four friends paused.

“Once upon a time we would have smelled the horses, the other cats, the poultry,” Sneaky mused.

“Oh, the humans don’t care. It’s all about them,” Pewter airily replied.

“And just how far would Mr. Jefferson have gotten if cats hadn’t kept the rodents out of the grain, out of the pantry, and furthermore, where would he get the goose quills for his writings?” Sneaky stood, transfixed by the magical view.

“You mean a goose helped write the Declaration of Independence?” Tally was far more transfixed by the lingering odor of a rabbit, who had recently scurried to her burrow.

Sneaky walked toward the front entrance. “Well, he couldn’t have done it without the quill, now, could he?”

“The door’s closed.” Tucker noticed the handblown glass in the special windows Mr. Jefferson had designed so they could also be used to go in and out of the house.

“I can see perfectly well,” Sneaky snapped. “I’m trying to remember where the little hole is, so we can crawl in and come up by the window in his bedroom.”

They walked to the left of the door, inspecting the ground.

“Was it here?” Tally found a small aperture in the foundation, which had been repaired.

“Damn. I hate all this improvement. Well, come on. Let’s go down to the kitchen and the walkways underneath. You know they’ll miss something,” Tucker suggested.

Trotting down to the brick labyrinth underneath the finely furnished rooms, the three gloried in the wonderful spring grass underfoot.

“Who goes there?” an irritated voice called out.

“Friends of Mr. Jefferson’s cats,” Sneaky called up to a house wren, now peering over her nest and none too happy at that.

“There are no cats here. The last housecat left with Dan and Lou Jordan.” The wren cited the former director of Monticello and his wife, who’d worked miracles at the place and had been loved by all, including the house wren.

“Guess that makes your life easier,” Pewter sassed.

“You couldn’t catch me if your life depended on it.”

“Really?” Pewter scratched the base of the wide tree. “Why don’t you come a little closer?”

“There should be cats at Monticello—along with cattle, horses, whatever Mr. Jefferson had living with him. We all improved his life and the lives of every human there.” Sneaky warmed to her subject. “They’d still be flying the Union Jack here if it weren’t for us.”

“I agree,” said the wren. “For a while, the Jordans had a kitty in the big house, but there was concern —don’t you love that word, ‘concern’?—that the cat might scratch a visitor.”

“That’s one of the reasons we’re here,” declared Sneaky. “Our human is at a meeting at Leslie and Court’s. She loves all this history stuff, so we thought we’d come along for the ride, and here’s why. If humans keep fading further and further from reality, which is to say nature, the day will come when even you will be removed from Monticello.”

A pleasing warble followed this. As she had a syrinx, the house wren could make two different sounds simultaneously. “Too much catnip, kitty.”

“Go ahead and make fun of me, but the day will come when someone will fund a study, some government type, to prove that your poop carries harmful genes. You and every other bird will have to be removed from Monticello, and they’ll take the caterpillars, too. Some of them bite, you know, and humans just hate insect bites.”

“I never thought of that.”

“Start thinking,” said Sneaky. “As it is an election year, folks are losing their common sense. Bird poop. I mean it.”

“What about poop?” asked the wren.

“Toilets. The humans think they’ve solved the problem, but then they really haven’t. Their poop still has to go somewhere.”

Читать дальше