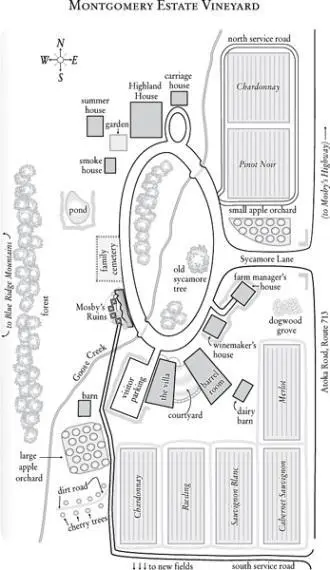

Ellen Crosby

The Viognier Vendetta

For Dominick Abel

And wine can of their wits the wise beguile,

Make the sage frolic, and the serious smile.

— Homer,

Odyssey , translated by Alexander Pope

When they ask me to become president of the United States,

I’m going to say, “Except for Washington, D.C.”

—Bernard Samson, character in

Spy Hook by Len Deighton

Ernest Hemingway once said you should always do sober what you said you’d do drunk because it would teach you to keep your mouth shut. It’s advice you remember the morning after when it’s too late and you’ve already given your word.

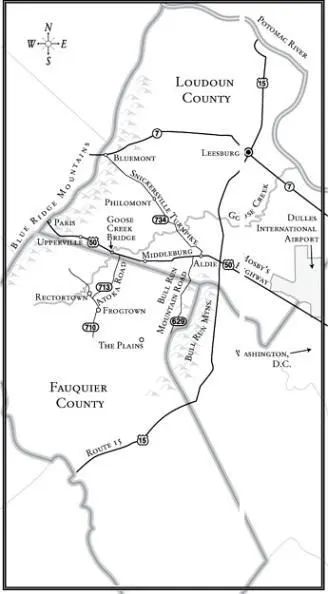

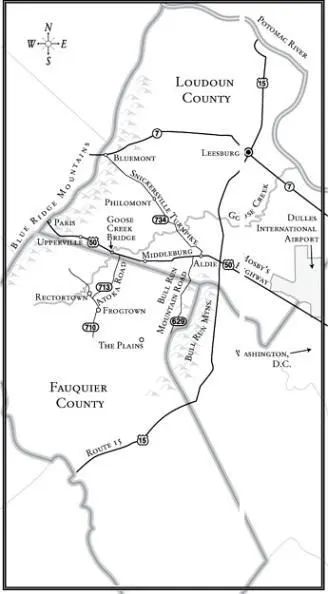

Sometimes it’s a big deal, like the wine-fueled discussion between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton over where to locate the capital city of the United States. In 1790, Jefferson dined with his nemesis Hamilton, plying him with so much Madeira that Hamilton fuzzily agreed to deliver enough Northern votes to pass a bill approving the Southern site President Washington had chosen along the Potomac River. In return, Jefferson promised that the federal government would assume all debts belonging to the thirteen states. If only it were that easy today.

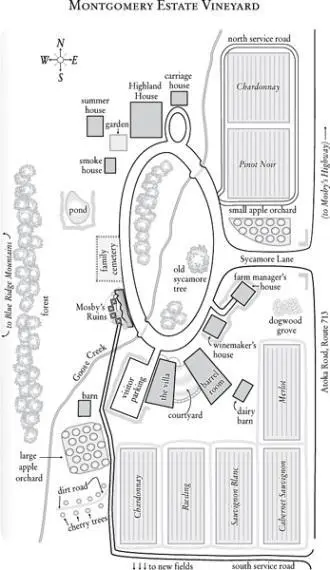

Sometimes it’s less significant, like my promise after drinking one too many glasses of my Virginia vineyard’s Viognier to get together with an old college friend in that same capital city. What I didn’t know at the time was that my decision to meet Rebecca Natale would be as life changing for me as the wine-soaked commitment to carve Washington, D.C., out of Maryland and Virginia was for the country.

The New York City area code popped up on my phone while I was reading in front of a dying fire one late March evening. The number wasn’t familiar, but my kid sister, the family gypsy, lived in Manhattan, where she flitted from a lover’s apartment to a friend’s couch to someone’s house-sitting arrangement. I never knew whose phone she’d borrow to call next. But this time it wasn’t Mia on the other end of the line. It was Rebecca. The last time I’d spoken to her was twelve years ago at her college graduation. After that she left her old life—and her old school friends—behind.

All she said was, “Hi, Lucie, it’s me.”

Just like that. Not a word about all those years with no phone call, no e-mail, no nothing. I never understood why she had cut me off. For a while it hurt. Finally I moved on—or thought I had.

I leaned back against the sofa and closed my eyes. Dammit, why now?

In retrospect, that should have been my first question. Instead I decided to match her sangfroid. “So it is. Long time no see, Rebecca.”

“I know, hasn’t it been? That’s why I’m calling. I’ll be in Washington the first weekend in April. I thought we could get together. Maybe you could come into town and stay with me?”

If she could be blasé about the gaping hole in the time line of our friendship, then so could I.

“A sightseeing trip for the cherry blossoms?”

“Oh, gosh no.” Her nervous laughter trilled like a scale. Maybe she wasn’t so blasé after all. “I work for Tommy Asher now. You might have seen the stories in Vanity Fair and Vogue. You do know about the Asher Collection being donated to the Library of Congress, don’t you?”

Actually I’d seen both articles—the fashion shoot in Vogue and the VF piece, “The Rise of Wall Street’s Recovery Whiz Kids.” Rebecca was the glamorous protégée of billionaire investor guru Sir Thomas Asher. Philanthropist, adventurer, and owner of a highly successful—and exclusive—New York investment firm, the eponymous Thomas Asher Investments. As for the library donation, you’d have to be living in a cave for the past few months not to know that he and Lady Asher were making one of the most significant gifts to the institution since Thomas Jefferson sold his personal library to replace what the British burned during the War of 1812. A collection of rare architectural drawings, maps, paintings, newspapers, and correspondence relating to the design and planning of Washington, D.C.

Curiosity outweighed anger and wine washed away some of the old hurt, so I told Rebecca I’d meet her. I even agreed to be her guest Saturday evening at a black-tie gala honoring her boss’s philanthropy and patronage of the arts. When she said it was rumored the president would attend, I nearly asked “president of what?” until I realized whom she meant.

The next morning I thought about calling back and explaining that something had come up.

But I didn’t.

Washington, D.C., shares a common bond with Brasília and Canberra, since all were invented to be the capital of a country. A peninsula formed by the Potomac and Anacostia rivers, and originally intended to be no more than a seasonal meeting place to conduct the nation’s business, it was referred to by Thomas Jefferson as “that Indian swamp in the wilderness.” Charles Dickens called the graceless, dirty backwater born of controversy, greed, and deceit the “City of Magnificent Intentions.” My late father, Leland Montgomery, said Washington was the place everyone who didn’t want to live in the United States went to live.

My French mother didn’t agree with any of them. She was captivated by the classic elegance of a city designed by Pierre L’Enfant, a fellow countryman who envisioned broad Versailles-like diagonal avenues overlapping a grid of streets resembling spiderwebs and graced by wedding cake public buildings of columns, domes, pediments, and porticoes in homage to the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome. When my brother, sister, and I were kids, she often made the one-hour drive into town so we could explore the museums, monuments, art galleries, parks, and theaters. After she died, I realized I’d become as seduced by Washington as she had been, but I also knew its dark, violent side away from the federal city, where drugs, crime, and poverty gave the place its other name: “Murder Capital of the United States.”

Rebecca had booked a suite for us at the Willard hotel, two blocks from the White House and a stone’s throw from the National Mall. The Willard is an iconic landmark, a place of Old World elegance and luxury with its lobby of elaborate mosaic floors, coffered ceilings, marbled columns, and Federal-style furniture grouped in discreet seating areas throughout the room.

Its nickname is “the residence of presidents” because every U.S. president since the hotel opened in 1850 has either visited or stayed there. Other luminaries on the guest list include Mark Twain, Houdini, Walt Whitman, Jenny Lind, and Mae West. Julia Ward Howe wrote “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” while staying there. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Willard.

A valet held the door as I walked into the splendid lobby past an enormous vase of hyacinths that graced a table of inlaid wood and mother-of-pearl. The old-fashioned clock above the mahogany and marble front desk said quarter to one. I gave my name to the clerk behind the desk and pulled out my credit card. He waved it away.

“It’s taken care of.” He reached for something from a bank of pigeonhole mailboxes that lined the wall behind him. An envelope. He handed it to me along with the small folder containing my room key card.

Читать дальше