Ellen Crosby

The Merlot Murders

For André

It has become quite a common proverb that in wine there is truth.

—Pliny the Elder

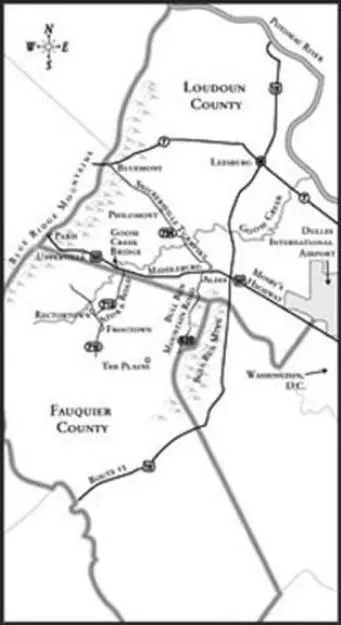

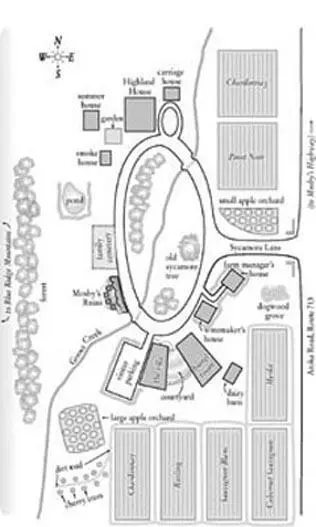

I have always been fascinated by alchemy, though I draw the line at black magic. My family owns a vineyard at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia and I am sure there is both magic and chemistry involved in transforming grapes into wine. Not as impossible as changing lead to gold, but nevertheless, no mean feat, particularly if you believe—as I do—in Galileo’s definition of wine as sunlight held together by water.

As a child I read the stories of the philosopher’s stone, how only a small quantity could convert a massive amount of worthless metal to gold and, supposedly, when added to wine or spirits, it became the mythical “elixir of life”—a potion that would cure illness, restore youth, and even grant immortality. Two years ago I moved to Grasse, the perfumed city in the south of France where my mother grew up, to recover from injuries sustained in a near-fatal car crash. I was twenty-six at the time and neither immortality nor eternal youth were much on my mind. All I wanted was to walk again. So I brought my own “elixir of life” hoping it would hasten my cure—bottles of wine from home.

Philippe, my live-in boyfriend, refused to drink any of it with me. A wine snob and a purist, the only wines he liked were listed in the Guide Hachette —and they were all French. So I drank my family’s wine when he wasn’t around.

Like now. This time he had to go to Italy. Another vague story about business and no idea when he’d be back. When he was home—an increasingly rare occurrence—he stayed up most nights talking on the telephone, smoking pack after pack of Gauloises. He never mentioned those conversations. I knew not to ask.

I seem to have a habit of getting involved with men who don’t sleep at night. A bartender, a paramedic, a law student moonlighting as a cabdriver—and now Philippe. There was a time when I slept deeply and soundly the minute my head touched the pillow—“sleeping on both ears,” the French call it. But the men who have drifted through my life have gradually turned me into a sheep-counting insomniac.

What kept me awake this night was the mistral—the dry, cold wind that began blowing from the north sometime after midnight. At sunset altocumulus clouds shaped like giant cuttlefish had turned blood red, a sure sign the winds would come that night. Tomorrow the late-August sky would be the luminous blue of a Van Gogh painting and windsurfers would flock to the beaches in droves. Tonight the mistral brought—as it always did—a raging headache.

I switched on the light and swung my feet out of bed, reaching for my cane, which was propped against the wall, where I always left it. I pulled on one of Philippe’s shirts, which was draped over a chair next to the bed. It smelled faintly of his cologne. His scent was about all that was left of our relationship.

The cracked marble floor was cool against my bare feet. When I got downstairs I took a bottle of Montgomery Cabernet Sauvignon from the wine rack, grabbed a glass and corkscrew, and let myself out the kitchen door into the garden.

I brushed against the large rosemary bush outside the door on my way across the terrace to the old stone swimming pool. The massive bank of lavender along one side of the pool was dark and dense against a blue-black sky filled with windblown stars.

Wine is inevitably linked to a place, tasting of the seasonal vagaries of sunshine and rain, the particularities of the soil, the differences in the taste of oak that hint at which forest yielded the trees for the fermenting barrels. I sat on a low garden wall by the pool and breathed deeply, getting quietly drunk on the calming smell of lavender and the velvety smoothness of the wine. But even the heady fragrance of the garden couldn’t overwhelm the scent and taste of Virginia as I drank, dissolving time and space, until the wine finally seeped into all the hidden paths that led to my heart.

Though I’d become comfortable and easy with my life in France, I wanted to go home again and rebuild my car-wrecked past. Through the open kitchen window I heard the phone ringing. At this hour it would be for Philippe.

I let it ring.

The caller was persistent. Finally I went inside, bringing the nearly empty bottle and my glass. I sat in a high-backed rush chair and picked up the phone mid-ring.

A man’s irritated voice said in English, “God, there you are. It’s about time. I’ve been calling for twenty minutes. How come your machine didn’t kick in? What took you so long to answer?”

“It wasn’t twenty minutes. You know we don’t have a machine. I was outside. Nice to talk to you, too, Eli,” I said to my older brother, glancing at the kitchen clock. It read two thirty-five A.M. Not the usual hour for a social call, even if he was phoning from America.

“I have some news, Lucie.” His voice was slightly less sharp.

“What is it?” I poured the last of the wine into my glass. To get through this conversation, I’d need it.

Eli and I have not been on the best of terms lately, so we don’t spend much time on chitchat. In fact, we don’t spend much time on anything. The last time I spoke to him was three or four months ago…or five. The fact that I have been living in the south of France for the past two years has made this chasm something we can blame on the Atlantic Ocean, pretending it’s physical distance, not an emotional divide that accounts for the estrangement.

“It’s Leland,” he said. “He was out hunting. There was an accident.”

“How bad?” I asked. But it was very bad, obviously, or he wouldn’t have called.

“He’s dead.” My brother’s heroes came from all the violent action movies he watched as a kid, full of emotionless men without tear ducts. Armageddon could be looming but they could handle it no sweat because they were tough. Just like Eli was acting right now. So I was surprised when he added gently, “I’m sorry, Lucie.”

“What happened?” I reached for my glass with an unsteady hand and almost knocked it over. I caught it just in time.

“He was alone, out in the vineyard. He had his shotgun with him so he was probably taking out a few crows. No one’s really sure what happened, but we’re thinking the heat might have gotten to him,” Eli said. “He passed out and the gun somehow went off.”

I tipped my head and drank the blood-red wine, wiping my mouth with the back of my hand. No way. Even I knew that guns don’t “somehow” go off. You have to pull the trigger.

Besides, despite his record on everything else, Leland Montgomery was never careless when guns were involved. He had his share of bizarre habits, like making his children call him “Leland” instead of “Dad” or “Pop” or “Father,” but he took no chances when it came to firearms.

“Who found him?” Eli’s story didn’t quite ring true.

The silence on the other end of the phone lengthened beyond the boundaries of a normal conversation as though the line had gone dead. It happened from time to time especially on international calls, so that on more than one occasion I’d ended up chattering into the flat blackness of a severed connection.

“Eli? Are you still there?”

Читать дальше