Ellen Crosby

The Chardonnay Charade

For Juanita Swedenburg,

and in memory of Wayne Swedenburg, with thanks;

and in memory of Skipp Hayes, with gratitude.

I could not stay another day,

To love, to laugh, to work or play;

Tasks left undone must stay that way.

And if my parting has left a void,

Then fill it with remembered joy.

—From “Remembered Joy,” an Irish prayer

If God forbade drinking, would he have made wine so good?

—Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu

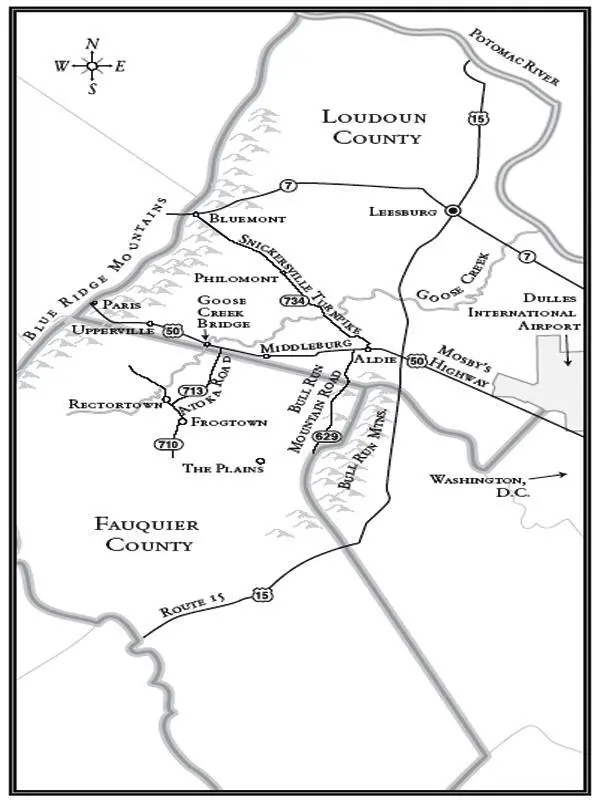

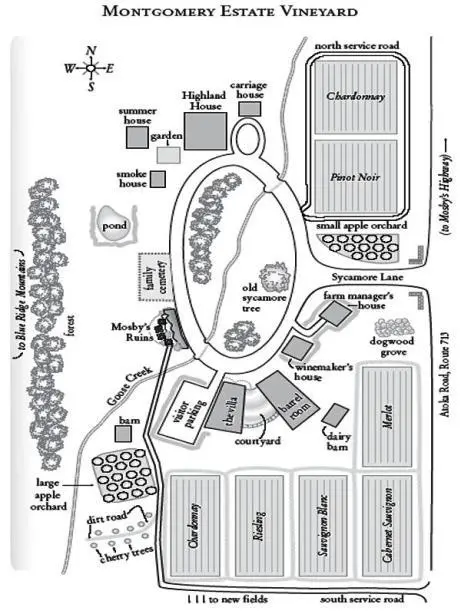

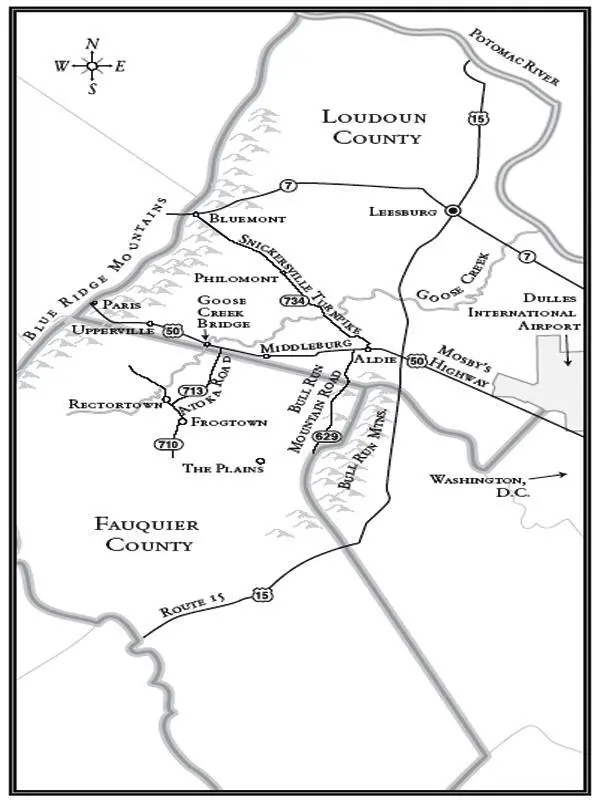

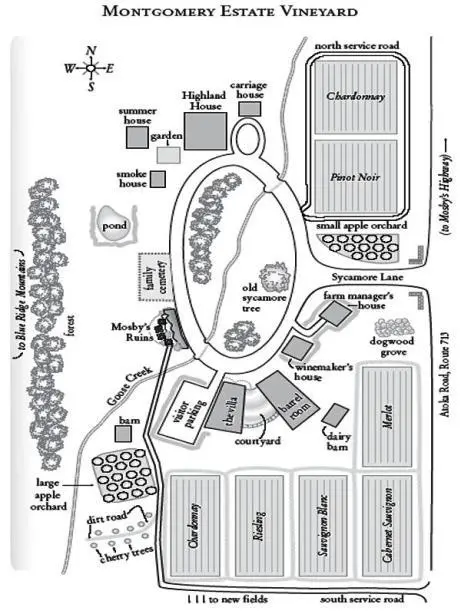

Some days I wish my life ran backward, because then I’d be ready for the catastrophes. Or at least I’d know whether there was a happy ending. I own a small vineyard at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Atoka, Virginia, where our winters are cold, our summers hot, and spring is the blissful season of growth and renewal. But not this year.

On what should have been a balmy May night, a warm air mass moving up from the Gulf of Mexico looked like it was going to smack into arctic winds sweeping down from Canada, causing temperatures to plummet below freezing. A week before Memorial Day, and Jack Frost nipping at our nose like early March. The weather forecaster on the Channel 2 news at noon recommended bringing tender young plants indoors for the night, “just to be sure.” A fine idea, unless you had twenty-five acres of tender young grapes.

A lot of science and math go into making wine, but most people don’t realize it’s also a hell of a crapshoot, meaning a hearty dose of guessing and finger-crossing figure into the equation, too. Mother Nature can always pull a fast one when you least expect it, and suddenly you’re scrambling—like we were this afternoon.

Normally I play it safe with my money and my business. Last fall, though, an unexpected financial windfall landed at my feet and I did something I swore I’d never do. I spent it. The money would go into clearing more acreage and planting new vines come spring. Literally a bet-the-farm gamble, since we were trying grapes we’d never grown before.

I’d expected Quinn Santori, my winemaker, to be as gung-ho about the decision as I was. Of the two of us, he was the risk-taker. Imagine my surprise when he made a case for planting less and using some of the cash to install wind turbines. Quinn had moved here from Napa eighteen months ago and he was still hard-wired for California, where turbines, which protect the grapes from late-season frosts, were common. I’d lived in Virginia for most of my twenty-eight years and we got that kind of killing frost once in a blue moon.

And since my family’s name was on every bottle of wine that left this vineyard, we did it my way. For the past few months we’d cleared land and plowed new fields. Thank God we hadn’t started planting yet.

Quinn never said “I told you so” once we heard that weather forecast, but he came close. My father had hired him shortly before he died last year and it had been a marriage of convenience. Leland needed someone to work on the cheap, freeing up money for his gambling habits and low-life business deals. Quinn wanted to make a new start in Virginia after his former employer’s decision to add tap water to his wines—boosting production for a black market business in Eastern Europe—had earned the ex-boss free room and board at a California penitentiary. When I took over running Montgomery Estate Vineyard nine months ago, I quickly found out that Quinn had a macho streak as wide as the Shenandoah River, a problem with authority, and a habit of speaking his mind with a candor polite folks would call unvarnished. If you happened to be a woman and also his boss, you would call it mouthy.

“Now that we’ve got our back to the wall thanks to you,” he said, “the only way we’re going to save our old vines is if we move that freezing air away from the grapes. Since we didn’t install turbines, we’d better get a helicopter in here. Expensive as hell, but beats waking up and finding we’ve got a few acres of frozen grapes we could use for buckshot.”

I closed my eyes and wondered how much “expensive as hell” cost—not that it made any difference. If I couldn’t hire a helicopter, we’d kiss about forty thousand dollars’ worth of wine goodbye in one night. At least we were only talking about the whites, since they were farthest along.

“I’ll get someone,” I said. “Don’t worry.”

“You’d better,” he said, “because I look pretty stupid strapping wings to my arms and flapping ’em around the vines like the paisanos do back in the old country. Besides, I got my hands full with the pesticide guys over in the new fields. They gotta get those protective tarps down right away.”

“They don’t really use wings and flap their arms in Italy, do they?” I asked.

He tucked his fists into his armpits and moved his elbows up and down. “Are you going to make those calls or aren’t you?”

I made the calls. Finally Chris Coronado from Coronado Aviation in Sterling said he’d take the job. “I’m not cheap, Lucie,” he said, “but I’m good. I’ve done this before.”

He flew to the vineyard later that afternoon to see the fields in daylight and mark the coordinates in the helicopter’s GPS navigation system so he could find them in the dark. His partner arrived in a Dodge pickup, towing a bright yellow fuel truck, which he parked near the Chardonnay block in the south vineyard. The pleasure of their company came to seven hundred and fifty dollars an hour for the helicopter, with an extra two-fifty for the fuel trailer.

Chris reckoned the temperature wouldn’t dip below thirty-two until three or four in the morning, meaning they would only be in the air for a few hours until dawn. So about thirty-two fifty for the night. Anything a smidge above the freezing mark and we were home, but not free—they still collected a thousand-dollar retainer and got to spend the night in the warm comfort of Quinn’s spare bedroom instead of fighting vertigo flying in near-total darkness above our vines.

So that Chris could see where he was going, we needed to put flashlights around the perimeter of the fields he would strafe, our own version of airport runway lights. I figured about forty would do the job. We owned eight.

Randy Hunter, one of our part-time field hands, walked into the tool room in the equipment barn while I was checking the batteries. Good-looking in a rough, tough cowboy way, mid-twenties, with bright blue eyes, curly blond hair, and a few days’ worth of grizzle that said sexy, not scruffy. When he wasn’t working for us, Randy delivered furniture for an antique shop and groceries for an upscale supermarket. In his spare time he worked out and played local gigs with his band, Southern Comfort. Maybe it was the slow, languid Louisiana drawl or maybe the way those ocean-blue eyes could caress, but Randy had a way of looking at a woman—any woman—like she’d been created just for him on God’s best day.

“What’re you doing, Lucie?” He set his heavy-duty gloves on the workbench and took off his leather jacket. I couldn’t help staring. Looked like he’d added another tattoo, this one around his muscular left bicep. Lightning bolts.

“I’m trying to figure out where I can get about thirty more flashlights in the next few hours,” I said.

Читать дальше