Rutledge thanked her and drove to Cambridge to ask for men to search the sides of the road between Sir John’s house and Mumford.

As they braved the cold to dig through ditches, and push aside winter-dead growth, Rutledge could hear the doctor’s voice again.

You’re the policeman. Tell me.

Three hours later, he drove once more to Cambridge to do just that. A few black hairs still clung to the dormouse’s ears, and on the base was what appeared to be a perfect print in Sir John’s blood.

Dead of Winter

RICHARD A. LUPOFF

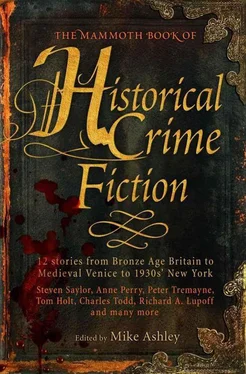

From the aftermath of the First World War to events leading up to the Second World War. As with the previous story, the following is based on certain characters and events that really happened. It concerns Nazi activities in the United States in preparation for the war effort in Europe.

Richard A. Lupoff is as well known for his science fiction as for his crime and mystery novels. His first book was a study of the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Master of Adventure (1965), and Lupoff became something of a master of adventure himself, but never with anything formulaic. Such books as One Million Centuries (1967) and Sacred Locomotive Flies (1971) rang the changes within science fiction, whilst Into the Aether (1974) was one of the early works of steampunk. A number of his books have been pastiches or tributes to some of Lupoff’s favourite authors, such as Lovecraft’s Book (1985), and readers will, of course, recognize the origins of his detective, Caligula Foxx, in the following story. Another Foxx story, “Cinquefoil” will be found in Lupoff’s collection Killer’s Dozen (2010).

Almost anyone would have been embarrassed to answer the doorbell wearing Buck Rogers pyjamas. Andy Winslow, however, felt no shame. His attitude was that anybody who sounded the brass gryphon knocker on the front door of Caligula Foxx’s house on West Adams Place had better be prepared for whatever sight he encountered. Especially if said caller arrived on a Sunday morning and sounded the knocker at the ungodly hour of — Winslow checked his Longines wristwatch and decided — well, it might not be such an ungodly hour at that, but it was Sunday morning.

Foxx was upstairs in his Colonial-era four-poster. The entire house was furnished with antiques, none of them dating from later than 1789 — when James Madison was said to have written the Bill of Rights on the polished maple desk that now served as Foxx’s daily working surface.

Reuter had prepared Foxx’s daily ration of steel-cut Irish oatmeal, moistened with a dab of freshly churned butter and a dash of heavy cream, and sweetened with a touch of maple sugar and cinnamon. A huge mug of Jamaican blue mountain coffee, seasoned with ground chicory root, Louisiana style, rested steaming on the tray beside the bowl of cereal. An array of Sunday newspapers covered the goose-down quilt on Foxx’s bed, the colourful comic pages set neatly in one pile, the rotogravure magazines in another, and so on through the various news sections of the papers.

No one interrupted the great detective while he was at breakfast, nor while he was reading his newspapers.

Hence, Andy Winslow to the front door.

He peered through the small fan-shaped window in the door but the caller, whoever that was, was nowhere to be seen. A light, early-winter snow had dusted West Adams Place during the night, painting the street itself a sparkling white, turning the graceful elm trees that lined the street into illustrations from a Currier and Ives print.

An automobile sped away, headed west, its exhaust rising in the crystal-like air. Winslow caught only a glimpse of it. He was pretty sure it was a LaSalle coupé and that it had a sticker of some sort, possibly an American eagle, in the back window. But it was gone before he could make a definite identification. Its licence plate, in any case, was obscured by snow.

Winslow opened the door.

A uniformed figure slid into the foyer. It was that of a youngster, garbed in military cap, tunic, and boots. As the newcomer collapsed on to the broad-plank floor of the foyer, a narrow streak of blood was drawn the length of the door. Winslow noticed a neat hole in the wood, then turned his attention to the uniformed figure.

He turned the newcomer over, face up. The military cap, knocked askew by the fall, still clung to dark, wavy hair, held there by rubber-tipped bobby pins. Winslow carefully removed the bobby pins and the cap. The hair fell free. The corpse — for there was no doubt in Andy Winslow’s mind that the newcomer was deceased — was that of a young woman, hardly more than a schoolgirl, garbed as a messenger for the Postal Telegraph Company.

A tiny hole, apparently the exit wound of a small-calibre bullet, formed a black circle just above the bridge of her nose. Winslow lifted her head, found a small section of her dark hair stained even darker with blood. Winslow had found the entry wound of the bullet.

A chilly gust swept a sprinkling of snow into the foyer. Winslow set the catch on the front door so he would not be locked out, then stepped on to the rounded brick porch. A bicycle stood leaning against the handrail. A few snowflakes had accumulated on it and more were continuing to do so.

Winslow touched the hole in the door, put his eye to it, and discerned a bullet therein. Apparently the messenger had been shot from behind just as she sounded the knocker. The bullet had penetrated the back of her skull, travelled through her brain, exited via her forehead, and come to rest a half inch deep in the antique polished oak.

A trail of fresh footprints in the new-fallen snow led from the opposite side of the street to the house, and back to the empty space at the curb where the LaSalle had stood. There was also a narrow furrow in the snow, obviously laid down by the bicycle that now leaned against the railing.

It appeared that the shooter had fired from the LaSalle and then walked — or, more likely, run — from the car to the brick porch. Then he had returned to the car and driven away.

Winslow stepped back into the house and closed the door. He could hear the voice of his employer bellowing out a demand. “Come up here, confound you, and tell me what all the abominable racket is about down there!”

Eschewing the small elevator that Foxx had ordered installed for his use, but concealed behind a faux bookcase of Colonial vintage, Winslow sprinted up the broad staircase. He gave Foxx a quick, breathless summary of the occurrence.

Foxx narrowed his eyes, fixing Winslow with a sharp stare. “You have a talent, my boy, for drawing trouble as a bar magnet draws iron filings. All right, phone Dr McClintock. I suppose we’ll have to bring the police into this as well, but let’s get Fergus on the case before those busybodies come snooping around.”

Winslow phoned the doctor and sketched out the situation for him. Fergus McClintock, MD, said that he’d be right over. Andy said, “You’d better drag your carcass out of that bed, Caligula, and put on some clothes before the doc gets here.”

Foxx took a large swallow of coffee, gave out a sound that was a cross between a sigh of pleasure and a grunt of resignation, and began the process of climbing from his four-poster. “You’d better get out of that funny page-outfit yourself,” he growled at Andy Winslow.

Winslow was out of his pyjamas, into street clothes, and back downstairs before Foxx was fully out of his bed. The casualty lay unmoving where she had fallen just inside the front door. Musing that it never hurt to be certain, Winslow laid his fingers on the messenger’s neck, expecting no pulse and cooling, clammy corpse-flesh. Instead, he felt warmth and detected a faint pulse.

Читать дальше