Cormac pulled up a chair beside the bed. “First of all, I’m not angry with you. I want to make sure you understand that.” The girl nodded. “Can you tell me what happened tonight?”

Tears welled in Eliana’s eyes. “I try to make sure he is all right before I sleep,” she said. “And tonight, he didn’t want me to go, I don’t know why, so I brought this.” Her fingers played with the edge of the duvet. “I didn’t mind.”

How was he going to explain to her? “Now, listen, Eliana, I want you to tell me, honestly. My father hasn’t said or done anything that’s made you feel… well, uncomfortable?”

“No, he’s very kind.” Then she pulled back, her eyes widening, suddenly aware of what Cormac was asking. “No, no, nothing has happened, I swear! I would never… please, you must believe me.”

“I do believe you, Eliana. Calm yourself.”

* * *

Back in their own room, Cormac’s conversation with Nora turned on what had just transpired and how they ought to handle it. He said, “I don’t think we should send her back to Dublin.”

“No, I agree.”

“So if we can just stick things out here for the next day or two, that would be best.”

“Do you want to call the agency, request someone else?”

“No, let’s wait until we get home and take things from there. It’s not as if Eliana has done anything wrong—perhaps she’s not exercised the best judgment—it’s my father who’s been making unreasonable demands.”

Nora smoothed the worry lines from his forehead. “We’ll figure all this out. And remember that it’s only temporary. Mrs. Hanafin will be back in ten days.”

Ten days. And then everything would go back to normal—at least to the ordinary strangeness of their quotidian life.

A whisper came from the darkness. “I meant to ask, Cormac, what were you doing up in the middle of the night?”

“The usual. Couldn’t sleep,” he said. No need to mention his fears about Niall, the shadowy dreams. He pushed all that away. Let Stella Cusack worry about solving Kavanagh’s murder. Not his business, any of it.

Nora’s silence told him that she had slipped back into slumber. He lay still and concentrated on breathing until he heard the faint sound of a footfall out in the corridor. If his father was going to start wandering the halls at four o’clock in the morning… He threw off the duvet and went to the door, cracking it open. No sign of his father, or Eliana. The only movement was Niall Dawson’s door across the way, closing silently.

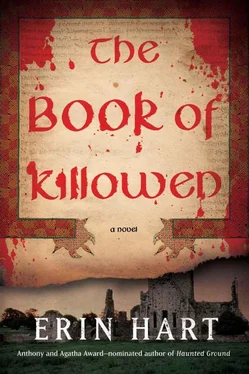

BOOK THREE

Oráit annso dona macaib fogluma

is catad in scel bec he

na tarbra aithbhir na litir orum—

is olc in dub

in memram gann

is dorcha an la.

A prayer here for the students;

and it is a hard little story:

do not reproach me concerning the letters—

the ink is bad,

the parchment scanty,

the day dark.

—A scribe’s note in Old Irish, inserted into a medieval Latin manuscript about Saint Finnian

Regina Mullens, the National Museum’s textile consultant, was already waiting outside the hospital morgue when Nora, Cormac, and Niall arrived a few minutes before eight. “I drove down last night,” she said in response to Dawson’s surprise. “Stopped with a friend who lives near Birr. I wanted a crack at your bog man as soon as possible.”

“Sorry to drag you all the way out here,” Dawson said. “Not exactly museum conditions, I’m afraid, but we’re not able to transport him back to Dublin just yet.”

“Extenuating circumstances,” Cormac explained.

“Really?” Mullens was intrigued. “Do tell.”

Dawson frowned and turned away slightly, so Cormac said, “It turns out that our bog man was found at a crime scene.”

“You’re joking.” Cormac shook his head, and suddenly Regina Mullens’s eyes opened wider. “Not that car buried in the bog? I saw the news reports last night. That was somewhere round here, was it?”

Dawson seemed annoyed. “Sorry, Regina, that’s all we can say, except that we can’t transport our man here to the Barracks until the crime scene has been thoroughly investigated and cleared. You understand, I’d have to ask you to keep this all under wraps anyway, extenuating circumstances or no.”

“Naturally.” Mullens pulled a zipper across her lips. “I shall be as silent as the grave.”

Niall Dawson opened the door to the morgue’s refrigeration unit where Killowen Man and the satchel were being stored. “I wanted to show you this first—we found it yesterday.” He and Cormac transferred the board supporting the satchel to the exam table and lifted away its form-fitting cast. The wet leather glistened under the mortuary lights. Mullens began to remove some of the surrounding peat, revealing a messenger-style bag with a full front flap.

“A beautiful piece of work,” Mullens said. “Look at those double-bound seams. I’m not sure we’ll be able to date it from construction alone; leather fabrication methods haven’t changed all that much over the years. I might guess somewhere between seventh and tenth century, but don’t hold me to it. Where did you say this was found, in relation to the body?”

Dawson’s eyes narrowed. “Nice try. What else can you tell us?”

“Well, the material looks like vegetable-tanned cowhide. DNA is iffy with bog specimens, but you can usually get a read on the species from the hair follicles.” She peered at the leather surface with a magnifier. “In sheep and pigskin, the hairs are grouped in threes, but on cow and calf hide they’re more evenly spaced. The seams appear to be sinew, which is good; vegetable-based thread would have been more fragile. I hope you had a look inside.”

Dawson shook his head. “No joy. I suppose it was daft, even thinking about it. No one’s ever found a book in a bog. Let’s wrap it up, have a look at our bog man.”

All four of them gloved up this time and began uncovering the body, one portion at a time. Each time they removed Killowen Man from his wrapping, they were opening the door to mold spores and bacteria, the destructive elements he’d so far managed to avoid, protected in his anaerobic, antiseptic bed. Mullens’s eyes grew large as she glimpsed the knob of the humerus protruding from the peat beside bog man’s chin.

“Jesus,” she whispered when the full extent of the damage was revealed. “You didn’t tell me he’d been pulled apart.”

“Whoever buried the car must have accidentally discovered the body,” Nora said. She glanced at Niall Dawson, who warned her with a frown not to say more. “Sorry, I shouldn’t have—”

Regina Mullens was watching both of them. “Now I’m dying of curiosity. But all right, I won’t ask any more questions. We’ll stick to his clothing. The good thing about wool is that it’s quite tough,” she said, “even after this long in a bog. From what I can see of the construction on this outer garment, it looks to be medieval, which could mean any time between the sixth and the sixteenth century.”

“Well, that helps narrow it down,” Cormac said.

“Dates might be difficult,” Mullens admitted. “It’s probably easier to figure out what social class he came from—there were all kinds of laws about who could wear what in ancient Ireland. Everything from permissible colors according to your status to the size of your brooch—it was all set down in the Senchus Mór .”

Читать дальше