Miguel Mejides - Havana Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Miguel Mejides - Havana Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2007, ISBN: 2007, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

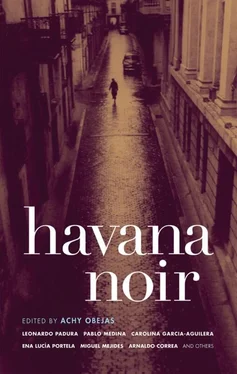

- Название:Havana Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-933354-38-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Havana Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Havana Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, authors uncover crimes of violence and loveless sex, of mental cruelty and greed, of self-preservation and collective hysteria, in a city characterized by ironic and wrenching contradictions.

Havana Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Havana Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

After forty-eight hours straight without sleep, I can’t think about anything. I go off on tangents, just letting the ideas flow however they wish. London. I’m supposed to go to London, next month at the latest. But I’m not exactly dying to do the paperwork. My Israeli passport is valid everywhere in the world, I think, except here. To get through security at the airport here, I have to use my Cuban passport, which means asking for an exit permit, something I find irritating. It makes me feel like a prisoner, though I know at this point in my life I should be used to these things. Although, in service to the truth, that’s not the only reason I’m reluctant to begin the process of traveling. Deep down, I don’t want to fly to London, or anywhere else, because I still hold out hope that the guy will call. If my suspicions turn out to be true, if he’s alive and well and loose in Havana, he will call me. Oh yes. He can’t not call me. It’s an essential part of his routine, we could even say its culmination. His thing is kidnapping, raping, killing... and then telling me all about it. If he calls, I’m going to go out with him. It’ll have to be quick, right away, before there’s another scattering of corpses and the whole city goes up in arms and something comes between us, whether it’s the police or an inopportune jerk like the Beast of Macagua 8. Yes, I’m going to dive into the black of night for once. It’s decided. Well, it’s always been decided. From that first call, when he described from A to Z what he was going to do to his victim that night, and I later realized he had in fact done it to the T, well, he proved he was no joker calling just to talk stupidities. That’s when I smelled blood. And I went on alert, just lying in wait. There’s no point in fooling myself: I’m a predator too. Except that I’m not turned on by bunnies, I’m not turned on by easy prey. No sir. What gets me hot is always difficult, always requires ingenuity, courage, and patience; it’s challenges. That’s why I’m going to fire a shot right into my dear Ted Bundy’s neck. I’ll be his last passenger. Later, who knows... maybe I’ll finally get some sleep.

Translation by Achy Obejas

The scene

by Mylene Fernández Pintado

Malecón

I was sitting on the terrace when the electricity went out over the part of the city that I can see from here. Just then I heard my mother calling me. She is very ill. She’ll die soon. I’ve got a calendar in the kitchen where I’ve circled two dates. One is my mother’s death. The other is the last day to move out of this building. I should have inverted the order, because we have to leave the building tomorrow and my mother has two weeks to live.

When my mother was first diagnosed, everyone who cares about her advised me to leave her at the hospital in the care of doctors and nurses in case of an emergency. A few volunteered to sit with her. These were the same people who insisted that I don’t love her, that I’m selfish and don’t know anything about sacrifice. They thought I couldn’t hear them, that I’d fallen asleep in the rocking chair I brought into my mother’s room so I can watch her while she rests, and to be near when she needs me.

When the building was in working order, we had a woman who came to take care of the house and a nurse who gave my mother her shots. But now they can’t climb so many stairs. Now I give my mother her shots and do all the grocery shopping. I’ve told my mother that these people don’t come anymore because we can’t afford to pay them. I don’t want to tell her that the building barely exists anymore.

There’s no one here but us now. And since they turned off the electricity, no one comes to visit. We live on the fourteenth floor and the elevator doesn’t work anymore. Nor the motor that pumps water. But none of that is important. All the water tanks on the roof are full. And there are a lot of them, so there’s water all day long and there will be water long after we don’t need it anymore. It’s true that the refrigerator doesn’t work, but I buy my mother’s drinking water already chilled at the market. I buy her food there too. She only eats ham-and-cheese croissants and ice cream. Or ate . Lately, she barely touches food; she makes a pained gesture and abandons the plate between the sheets.

I found out about the city’s plans for our building when I was asked to a meeting at the office of Architecture and Urbanism near our home. It was on the twentieth floor on Malecón Avenue, with a view of the sea. The hallway walls were full of photos of our neighborhood in Vedado. Sometimes I think Vedado is so scattered and rife with transients that it’s difficult to think of it as one neighborhood, but rather many. People like to come here, to go to Coppelia dressed in their Sunday best and spend the entire day in line, to stroll La Rampa on the sidewalks still carved with things by Lam and Mariano. They go to the movies and sit along the Malecón.

The same exact photos were on the office wall too. There was one of the seawall on the Malecón. The most curious thing was that there was no one on the seawall in the photo. Not a single fisherman or couples kissing, not one kid playing. There were no brave suicides portrayed, depressed poets, drunks, street musicians, or hustlers. It must have been one of those scenes they can create now on computers. Just erase all the people with a touch of a button.

The other photos were busier. People strolling on La Rampa, cars on Paseo and Avenue of the Presidents. Coppelia without lines, with satisfied customers eating different flavors of ice cream.

Since the man I was meeting took his time, I looked at the photos and then at the city from the balcony next to the office. There are little homemade structures all over the rooftops, mansions turned into barracks, houses that can barely stand. The rooftops have become dovecots. There are fields of laundry lines; residue of homeless people; plants that grow between the tiles on the eaves; dogs that can’t be kept inside anymore so that instead of guarding homes, they’ve turned into lookouts who scan the horizon. Sun-drenched treetops, humid and green; church steeples. Little gray streets, a few cobblestone, which intersect, sometimes timidly, as if hiding from the multitudes. And then the sea, always lying in wait, and the Malecón which keeps us safe. It’s a wall of lamentation, the entrance to and from the country of Never Again, a fixture on postcards and calendars. Therapy for my mother.

Every time my mother could gather her strength to get up, she’d ask me to take her out on the terrace. With the very first remittance sent by my brother from San Francisco — once he realized that experiencing the spectacle of my mother in the process of dying would affect his biorhythm and would keep him from his successful life as a designer — I bought a lounge chair, a down pillow, and a thin mattress pad, and she began to spend her hours sitting out there. I brought her books. But later I realized she preferred chatting. Still later, it became clear that what she wanted more than anything was to gaze at the part of the city that was ours. One day she said, in a whisper, that she’d never had much time to look at the sky and that the clouds passed much too quickly.

On those afternoons, she discovered a million things. She heard the sound of the bells from San Juan of Letrán and the songs from the day care center nearby; the whistle of the scissors sharpener; the riot of pigeon wings on the roof across from us. And then, as soon as the sun started buzzing on the water, I’d take her back to her room.

We talked about the buildings around us and what they might be like inside. We would describe those we’d actually visited and later make ambitious plans about how we would renovate them without tearing down the original structures.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Havana Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Havana Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Havana Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.