Miguel Mejides - Havana Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Miguel Mejides - Havana Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2007, ISBN: 2007, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

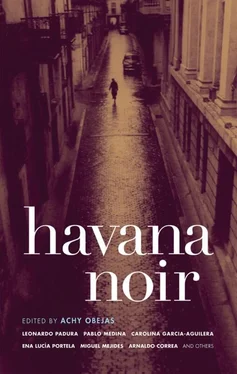

- Название:Havana Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-933354-38-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Havana Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Havana Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, authors uncover crimes of violence and loveless sex, of mental cruelty and greed, of self-preservation and collective hysteria, in a city characterized by ironic and wrenching contradictions.

Havana Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Havana Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I had time to think about all this until the man I was meeting came and asked me into his office. Almost giddy as he spoke, he explained that our building would be going through a major renovation, and that the current tenants would be given new housing according to their needs. I explained that we needed to stay. I told him about the situation with my mother and that I wasn’t sure we could move her.

The man understood that my situation was delicate. But so was his. He had plans to complete, deadlines and tasks, expenses that had been given the okay in order to procure resources. Everything was architecturally and financially aligned. Emptying the building was just the first task. But he could give me an extension. I smiled — sometimes I can be truly charming — and thanked him. As we were saying goodbye, I felt that he wanted to say something, maybe just the usual good wishes for recuperation, but he seemed to think better of it and kept quiet.

That same day, I met with the doctor; I was ready to have my mother at home until the day she died. I explained about the therapeutic qualities of the terrace, how she delighted in the architectural view, the sea, and the dawn. I told him I’d been born in that neighborhood, in that house, and that my mother felt in her element there. I said nothing about the plans to empty out the building.

The doctor was glad to hear our home was fresh and high up, with sun and light, air and space. He was also glad it had such a good view of the water and said that Vedado reminded him of Manhattan. I nodded so he’d feel comfortable and I got his approval. He told me that if I made sure we had the proper conditions, I could keep her there until she died.

I then quickly talked to him about my brother and his help. The doctor asked if my brother had any plans to visit my mother. I lied, saying that his papers were still not in order and that he suffered a lot because he couldn’t come.

A few weeks after that, my neighbors began moving out of the building, many coming by for a last goodbye. But my mother didn’t pay much attention to them. The morphine and phenobarbital left her with just a few lucid moments, and I took advantage of them to bring her out on the terrace, where we would continue “renovating” Vedado. Everyone asked when we were leaving. Everybody was very concerned about the work on the building and how soon even the most minimal of services would be unavailable. I calmed them down, saying that everything was ready, that I’d made the pertinent arrangements with the hospital to comfortably transport my mother using a powerful anesthetic the minute the psychologist determined it was appropriate.

After they all left, there came a happy time, having a sixteen-story building all to ourselves, knowing that no neighbor would stop me in the hallways to ask me the same things: how she was this morning, how much morphine she was taking, if she was eating, when my brother was coming, and, poor woman, what bad luck... I never gave an honest answer: My mother woke up radiant every day, spent hours entertained with her 2000-piece jigsaw puzzles (her collection of puzzles, all famous portraits, was well known), and the morphine was just so she’d sleep quietly. The stampede out of the building spared me the obligation of lying to them all, though I’d never felt the slightest bit guilty about it.

The best part was the sensation that came over me when I arrived home after getting morphine, or juice, or phenobarbital, the syringes, or something for her cravings. I walked 17th Street in the shade of the laurel trees and came in the entrance without worrying about the manager, vendors, or people looking to trade housing, knowing that I had exclusive rights to the place. There was no one murmuring behind the doors that my brother was a jerk who thought money could solve everything, or that I have a heart of steel and what I really wanted was for my mother to finally die. The theories vary on this last hypothesis.

The simplest one is that I’ll finally be able to go live with my brother. The truth is that we were always very close; the two of us would play house, and cowboys, and later we both ended up studying art and architecture. He adored the houses designed by Le Corbusier and I was taken by the Impressionists. Now he’s in San Francisco, sending money so I don’t need to do anything other than care for our mother until she dies.

Another theory, which requires more neighborly shrewdness but is actually expired, is related to the Sorbonne professor who used to visit me because he was interested in the Cuban movie posters I had once researched. He would come by frequently, long after he’d viewed the entire national poster collection, finished his thesis, and curated his exhibit. Then the real goal of his visits became sleeping together as much as possible, to which I had no objections. Just around the time my mother got sick, he invited me to Paris to give a series of presentations on how the French posters of 1968 had influenced Cuba. Though I wrote out my script at first, I ultimately answered that I could not travel because of my mother’s illness. And I apologized, as though my mother’s death were a mere inconvenience disrupting his magnum plans. He has never written again.

For those neighbors who don’t sign on to either of those two theories, there’s a more general option, which doesn’t really pin anything concrete on me. According to this one, I want to be free so I can do whatever I want, like sleep with lots of men and women; drink until I fall on my ass; smoke marijuana and take pills and watch a lot of porno films on giant screens with quadraphonic sound. In other words, to manifest this dark side which my ex-neighbors insist on having seen in me since I was a little girl. They’re convinced that my mother not having left for paradise yet is the only reason I haven’t descended into hell.

Now that we’re without them — they’re far away, furnishing other homes and surely missing Vedado and its excellent bus routes (on which no buses actually pass) and its movie theaters (always without air-conditioning in the summer) and Coppelia (with its serpentine lines) and the Malecón (which is the only real populated part of Vedado, because it’s free) — my mother and I are quite content.

She doesn’t know that the neighbors have moved out and so she innocently enjoys the magical breeze that has blown away the radio and its shrill music, the hammering at 6 in the morning, dogs barking all through the night, fights between parents and children, brothers and sisters, husbands and wives.

A little after the neighbors left, our phone was disconnected. I thought God was on my side. In any case, I’d had it off the hook for most of the last few weeks. That was how I had avoided giving a health report every five minutes to the curious; the worst part was hearing their comforting words and the sense that, behind them, there was such relief that it was my mother and not theirs who was about to ride with Charon.

When they cut the gas, I started using the two-burner hotplate we kept for emergencies. My mother was eating less every day. So when we finally lost our electricity too, there wasn’t much to worry about.

I fired the nurse, who cried a bit as she showed me how to give my mother her shots, regulate the oxygen pump, take her blood pressure, and raise the Fowler bed to the right height so my mother could get up. I also learned to smile when I wanted to cry and to convince myself that she was going to die anyway.

We have been very happy here, my mother and I, absolute rulers of this beautiful building in ruins, I thought as I left the terrace to answer my mother’s call on the last night in my neighborhood. When I went back, the city was black. I imagined that the tourists on the cruise ship — the only line of lights on the water — must have a very interesting view. What must it be like to face a city completely in the dark?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Havana Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Havana Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Havana Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.