Harry Brearley - Time Telling through the Ages

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Harry Brearley - Time Telling through the Ages» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Time Telling through the Ages

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Time Telling through the Ages: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Time Telling through the Ages»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Time Telling through the Ages — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Time Telling through the Ages», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Second. The tool-using man, who had begun to grasp weapons and to fashion implements, thus supplementing his natural abilities by artificial means.

Third. The machine-making man, who has fashioned to himself a mechanical "body" of incredible powers – that is to say, he has learned to intensify his own powers through artificial means which he has invented, as when he made the telescope to give himself greater vision; he has made inventions by means of which he can outrun the antelopes, outfly the birds, outswim the fishes, outgaze the eagles, and overmatch the elephants in sheer physical force – he can turn night into day, can send his voice across the continent, can strike crushing blows at a distance of many miles and can carry the movements of the stars in his pocket. Some phases of this third stage were foreshadowed when man first applied wheels and pulleys to his clepsydra.

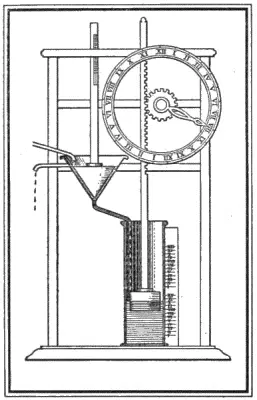

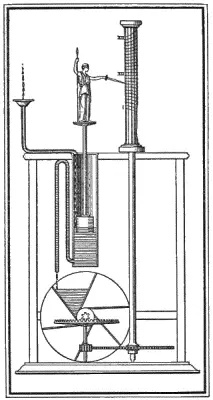

Here, then, was water steadily raised or lowered by means of uniform dropping; here was a float whose motion was controlled by that of the water; here, in fact, was water-power with a means for applying it. Attach a cord to the float, cause it to turn a wheel by use of the pulley-principle, and the motion of the wheel would indicate the time. Still better, rig up a turning-pointer, increase its speed through the use of toothed gear-wheels, place it in front of a stationary disk divided to indicate the hours, and now the apparatus looked not unlike a modern clock. Or attach a bell and let it be caused to ring at a certain point in the motion – what was that but an alarm-clock? Ctesibus of Alexandra was the one who is believed first to have applied the toothed wheels to the clepsydra and this was about 140 B. C.

Clepsydrae were expensive of course; accurate mechanical work was never cheap until modern times. Cunning craftsmen spent their time upon costly decorations, and these water-clocks became triumphs of the jeweler's art, a gift for kings. Therefore, like the sun-dial, they drifted into Rome – that vast maelstrom of the ancient world. Imagine a great walled city of low flat-roofed buildings, with fronts and porches of great columns, a town mostly of stone and much of it of marble, gleaming white under the bright Italian sun, the streets thronged with men in tunics and togas and here and there some person of importance driving by, standing erect in his chariot drawn by four horses harnessed abreast. And statues everywhere, in the streets and about the buildings and in cool courtyards and gardens among green leaves. The ancients thought of sculpture as an outdoor thing, and where we have one statue in the streets or public places of our cities, they had a hundred. We treasure the remains of them as artistic wonders in our museums, but they put them indoors and out as common ornaments, and lived among them.

Presently we hear of the clepsydra being used in Roman law courts by command of Pompey, to limit the time of speakers. "This," says one writer of the day, "was to prevent babblings, that such as spoke ought to be brief in their speeches." It is not difficult to picture some pompous and tiresome togaed advocate, rolling out sonorous Latin syllables as he cites precedents and builds up arguments, while an unseen dropping checks the time against him, and to hear his indignant surprise – and the chuckles of his auditors – when the relentless water-clock cuts him short in the middle of some period. Martial, the Latin poet, referring to a tiresome speaker who repeatedly moistened his throat from a glass of water during the lengthy speech, suggested that it would be an equal relief to him and to his audience, if he were to drink from the clepsydra. But Roman lawyers were not guileless, and sometimes, so we are told, they tampered with the mechanical regulation or else introduced muddy water, which would run out more slowly.

This suggests one of the difficulties of the clepsydra. Still more serious was the fact that it would freeze on frosty nights. There were no Pearys among the ancient Romans; polar exploration interested them not at all; but they did spread their conquests into regions of colder weather – as when Julius Caesar mentions using the clepsydra to regulate the length of the night-watches in Britain. His keen mind noted by this means that the summer nights in Britain were shorter than those at Rome, a fact now known to be due to difference of latitude.

As late as the ninth century, a clepsydra was regarded as a princely gift. It is said, that the good caliph, Harun-al-Raschid, beloved by all readers of the "Arabian Nights," sent one of great beauty to Charlemagne, the Emperor of the West. Its case was elaborate, and, at the stroke of each hour, small doors opened to give passage to cavaliers. After the twelfth hour these cavaliers retired into the case. The striking apparatus consisted of small balls which dropped into a resounding basin underneath.

The clepsydra appears to have been used throughout the Middle Ages in some European countries, and it lingered along in Italy and France down to the close of the fifteenth century. Some of these water-clocks were plain tin tubes; some were hollow cups, each with a tiny hole at the bottom, which were placed in water and gradually filled and sank in a definite space of time.

When the clepsydra was introduced from Egypt into Greece, and later into Rome, one was considered enough for each town and was set in the market-place or some public square. It was carefully guarded by a civic officer, who religiously filled it at stated times. The nobility of the town and the wealthy people sent their servants to find out the exact time, while the poorer inhabitants were informed occasionally by the sound of the horn which was blown by the attendant of the clepsydra to denote the hour of changing the guard. This was much in the spirit of the calls of the watchmen in old England, and later in our New England, who were, in a way, walking clocks that shouted "Eleven o'clock and all's well," or whatever might be the hour.

Allowing for the fact that the clepsydra was none too accurate at the best and that its reservoir must occasionally be refilled, it can be seen that this early form of timepiece, having played its part, was ready to step off the stage when a more practical successor should arrive.

With one of its earliest successors we are familiar.

CHAPTER FIVE

How Father Time Got His Hour-Glass

Every now and then one sees a picture of a lean old gentleman, with a long white beard, flowing robes, and an expression of most misleading benignity. In spite of his look of kindly good humor, he is none too popular with the human race and his methods are not always of the gentlest. In one hand he carries the familiar scythe, and, in the other, the even more familiar hour-glass. By this we may assume that he began to be pictured in this way while the hour-glass was still in common use.

The principle of the hour-glass is so similar to that of the clepsydra, and its first use was so early, that it is somewhat of a misnomer to speak of it as a successor. About the only justification that can be made is that the clepsydra has long disappeared, while the sand-glass – if not the hour-glass – is still sold in the stores for such familiar uses as timing the boiling of eggs, the length of telephone-conversations, and other short-time needs.

Nothing could be much simpler than the hour-glass, in which fine sand poured through a tiny hole from an upper into a lower compartment. It had none of the mechanical features of the later clepsydræ; it did not adjust itself to astronomical laws like the perfected sun-dials; it merely permitted a steady stream of fine sand to pass through an opening at a uniform rate of speed, until one of the funnel-shaped bowls had emptied itself – then waited with entire unconcern until some one stood it upon its head and caused the sand to run back again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Time Telling through the Ages»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Time Telling through the Ages» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Time Telling through the Ages» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.