Sabine Baring-Gould - A Book of the Pyrenees

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sabine Baring-Gould - A Book of the Pyrenees» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Book of the Pyrenees

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Book of the Pyrenees: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Book of the Pyrenees»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Book of the Pyrenees — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Book of the Pyrenees», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

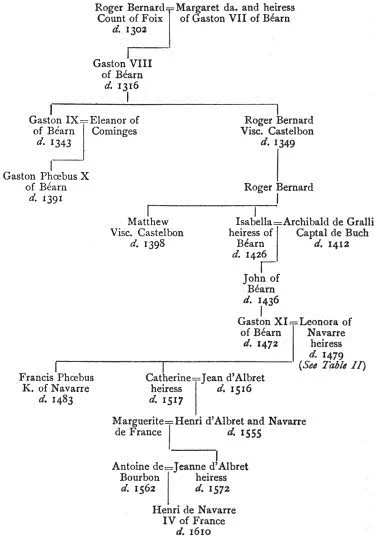

William Raymond died in 1223, leaving a son, William, to succeed him, but he was killed in battle against the Moors in 1229, and William’s son Gaston succeeded under the regency of his mother Garsende. She is described as having been so stout that only a large wagon could contain her, and then she overlapped the sides. Gaston VII, son of this plump lady, left an only child, a daughter Margaret, the heiress of Béarn, which she carried with her when married to Roger Bernard, Count of Foix. Thus it came about that Foix and Béarn were united in one hand.

I. PEDIGREE OF THE VISCOUNTS OF BÉARN, COUNTS OF FOIX

II. PEDIGREE OF LEONORA, HEIRESS OF NAVARRE

Roger Bernard and Margaret had a grandson, Gaston IX of Béarn. At the age of eighteen he was married to Eleanor of Cominges, a lady considerably older than himself. Some one without tact remarked to the Countess on the disparity of their ages. “Disparity of ages!” exclaimed she, “Why, I would have waited for him till he was born.”

The young husband fell fighting against the Moors in 1343. By his elderly wife he left a son, Gaston Phœbus, of whom more when we come to Orthez.

Gaston Phœbus was succeeded by a cousin, Matthew de Castelbon, who died in 1398, without issue, and he was followed by his sister Isabella, married to Archibald, Captal de Buch, a just and worthy ruler. They had a son, John of Béarn, who succeeded his mother in 1426. He captured the antipope, Benedict XIII, and threw him into a dungeon in one of his castles, where he died of ill-treatment, and then John denied Christian burial to his body. This so delighted Pope Martin, the rival of Benedict, that he conferred on John the title of “Avenger of the Faith.” Jean was succeeded by his son Gaston, who placed his sword at the disposal of Charles VI. At Bordeaux with his aid the English underwent a signal defeat. He was married to Eleanor of Navarre, through whom the claim to the title of King of Navarre came to her descendants. How that was, and the crimes that brought it about, must now be told.

Charles the Noble, King of Navarre, died in 1425. Having lost his only son, he bequeathed crown and kingdom to his daughter Blanche, married to Juan of Aragon, brother of Alphonso, King of Aragon and the Two Sicilies, and by reversion after her death to their son Charles, Prince of Viana. Juan of Aragon acted as viceroy to his brother whilst Alphonso was in Italy. On the death of Charles the Noble Juan and Blanche assumed the titles of King and Queen of Navarre. Blanche died in 1441, and by her will bequeathed the kingdom, in accordance with her father’s desire, to her son Charles of Viana. But Juan had no thought of surrendering the crown to his son. He married a young, handsome, and ambitious woman, Juana Henriquez, daughter of the Admiral of Castille, and she became the mother of Ferdinand, afterwards known as “the Catholic.” Thenceforth she schemed to obtain all that could be grasped for her own son Ferdinand.

Charles was an amiable, accomplished youth, fond of literature and of the arts. Queen Blanche, in her will, had urged him not to assume the government without the consent of his father; but when, in 1452, the estates of Aragon recognized him as heir to the crown, and Juan declined to resign, Charles openly raised the standard of revolt. Juan marched against his son, and Charles was defeated, taken prisoner, and consigned to a fortress. There he remained for a year, and would have remained on indefinitely had not the Navarrese armed for his deliverance. Juan was forced to yield, and as a compromise confirmed Charles in the principality of Viana, and promised to abandon to him half the royal revenues.

The reconciliation thus forcibly effected was not likely to last; in fact, the compromise suited neither party. The father burned to chastise sharply his rebellious son, and Charles chafed at being defrauded of the crown which was his undoubted heritage. Hence in 1455 both prepared to renew the contest. The following year, 1456, the prince was again defeated by his father, and was compelled to fly to his uncle Alphonso, who was then at Naples. During his absence Juan summoned the estates and declared that both Charles and his eldest daughter Blanche were excluded from succession to the throne – Charles on account of his rebellion, Blanche for having espoused his cause – and Juan proclaimed his youngest daughter Leonora to be his heir. Blanche had been married to, and then separated from, Henry the Impotent, King of Castille. Leonora was married to the Count of Foix.

The inhabitants of Pampeluna, and the people generally throughout Navarre, were indignant at the injustice committed by Juan; they elected Charles to be their king, and invited him to ascend the throne. Unfortunately for him, Alphonso, King of Aragon and the Two Sicilies, died in 1458, whereupon Juan ascended the throne that had been occupied by his brother. Charles now hoped for a reconciliation, which he had reason to expect, as his father now wore three crowns which had come to him by right; and he hoped that Juan would readily surrender to him that of Navarre, which he had usurped, and to which he had no legitimate claim. The Prince of Viana landed in Spain in 1459, and dispatched a messenger to Juan entreating him to forget the past and to recognize his claim to Navarre at present and his right to succession to Aragon. But Juan would allow nothing further than restoration to the principality of Viana, and expressly forbade his son setting foot in Navarre. Had the misunderstanding ended here, it had been well for Charles; but a new occasion of dispute arose.

Henry IV of Castille offered his sister Isabella, heiress to the crown after his death, to Charles of Viana. This alarmed and enraged Juana, the stepmother of Charles, who calculated on effecting this alliance for her own son Ferdinand, and uniting under his sceptre the kingdoms of Aragon and Castille. To obtain this end Charles must be got rid of. Accordingly she induced his father Juan to invite him to a conference at Lerida. The prince went thither unsuspiciously, and was at once arrested and thrown into prison. The Estates of Aragon and Catalonia were incensed at the harsh and unjust treatment of one whom they hoped eventually to proclaim as their sovereign. They demanded his liberation. The King refused. Insurrection broke out, became general, and so menacing that Queen Juana was alarmed and herself solicited the release of the Prince. She did more; she went in person to Morella, whither the captive had been transferred, to open the prison gates. He was conducted by her to Barcelona, which admitted him, but shut its gates in her face. All Catalonia now recognized the Prince, and proclaimed him heir to the thrones of Aragon, Navarre, and Sicily. But the rejoicing of the people was of brief duration, as shortly after his release from durance Charles fell ill, lingered a few days, and died. By his testament he bequeathed the crown of Navarre to his sister Blanche as next in order of succession to himself.

The death of Charles was too opportune for it not to have been attributed to poison, administered by an agent of his stepmother. Soon after a ray of sunlight focussed by a mirror set fire to Juana’s hair. This was at once set down as a Judgment of Heaven falling on her, an indication by the finger of God that she was the murderess of her stepson.

Charles was now out of the way; Blanche, however, obstructed the path, and the will of her brother in her favour proved fatal to her. Juan was resolved to retain the sovereignty of Navarre during his own life, and none the less to transmit it at death to his favourite daughter Leonora, Countess of Foix, or her issue. He determined to compel Blanche to renounce her rights. To effect this she was sent across the Pyrenees, closely guarded, under the pretext that she was about to be given in marriage to the Duke of Berri, brother of the French king. But she perceived clearly enough what was her father’s purpose, and at Roncevaux, on her way, she caused a protest to be prepared in all secrecy, in which she declared that she was being carried out of Spain by violence, against her will, and that force would be used to compel her to renounce her rights over Navarre; and now she declared beforehand against the validity of such a renunciation. Upon reaching S. Jean-Pied-du-port, she was, as she had anticipated, constrained to make a formal surrender of all her rights, in favour of her sister and brother-in-law, Gaston, Count of Foix. In a letter addressed to Henry, couched in pathetic terms, she reminded him of the dawn of happiness that she had enjoyed when united to him years before, of his promises made to her, and of her subsequent sorrows. As she was well aware that her father was consigning her to imprisonment, and perhaps death at the hands of her ambitious and unscrupulous sister, she conferred on him all her rights to the crown of Navarre, to the exclusion of those who meditated her assassination, the Count and Countess of Foix. On the same day that this letter was dispatched she was handed over to an emissary of the Countess Leonora, 30 April, 1462, and was conveyed to the Castle of Orthez. The gates closed on her, and she was seen no more, but not long after they opened to allow a coffin to issue to be conveyed to Lescar, there to be interred.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Book of the Pyrenees»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Book of the Pyrenees» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Book of the Pyrenees» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.