Richard Garnett - The Age of Dryden

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Garnett - The Age of Dryden» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Age of Dryden

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Age of Dryden: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Age of Dryden»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Age of Dryden — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Age of Dryden», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Le donne, i cavalier, l’arme, gli amori,

Le cortesie, l’audaci imprese io canto.’

If this is true of portions of Palamon and Arcite , it is still truer of The Flower and the Leaf (then believed to be a genuine work of Chaucer’s), throughout a most brilliant picture of natural beauty and courtly glitter, painted in language of chastened splendour. The other pieces modelled after Chaucer are of inferior interest, yet all excellent in their way. Two of the three tales from Boccaccio are acknowledged masterpieces, Cymon and Iphigenia and Theodore and Honoria . The interest of the first chiefly consists in the narrative itself, and that of the second in the way of telling it. The story, indeed, though striking, is fantastic and hardly pleasing, but Dryden’s treatment of it is perhaps the most perfect specimen in our language of l’art de conter .

An example of Dryden’s descriptive power may be given in a passage from The Flower and the Leaf :

‘Thus while I sat intent to see and hear,

And drew perfumes of more than vital air,

All suddenly I heard the approaching sound

Of vocal music, on the enchanted ground:

At length there issued from the grove behind

A fair assembly of the female kind:

A train less fair, as ancient fathers tell,

Seduced the sons of heaven to rebel.

I pass their forms, and every charming grace;

Less than an angel would their worth debase:

But their attire, like liveries of a kind,

All rich and rare, is fresh within my mind.

In velvet white as snow the troop was gown’d,

The seams with sparkling emeralds set around:

Their hoods and sleeves the same; and purpled o’er

With diamonds, pearls, and all the shining store

Of eastern pomp; their long-descending train

With rubies edged, and sapphires, swept the plain.

High on their heads, with jewels richly set,

Each lady wore a radiant coronet.

Beneath the circles, all the choir was graced

With chaplets green on their fair foreheads placed;

Of laurel some, of woodbine many more,

And wreath of Agnus castus others bore:

These last, who with those virgin crowns were dress’d,

Appear’d in higher honour than the rest.

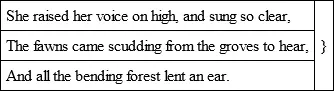

She in the midst began with sober grace;

Her servants’ eyes were fix’d upon her face,

And as she moved or turn’d, her motions view’d,

Her measures kept, and step by step pursued.

Methought she trod the ground with greater grace,

With more of godhead shining in her face;

And as in beauty she surpass’d the choir,

So, nobler than the rest was her attire.

A crown of ruddy gold inclosed her brow,

Plain without pomp, and rich without a show:

A branch of Agnus castus in her hand

She bore aloft (her sceptre of command;)

Admired, adored by all the circling crowd,

For wheresoe’er she turn’d her face, they bow’d.

And as she danced, a roundelay she sung,

In honour of the laurel, ever young.

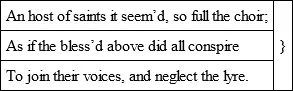

At every close she made, the attending throng

Replied, and bore the burden of the song:

So just, so small, yet in so sweet a note,

It seem’d the music melted in the throat.’

One remarkable feature of the principal poets of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is the infrequency of the casual visitations of the Muse. They seem to have hardly ever experienced an unsought lyrical inspiration, or to have sung merely for singing’s sake. Hence Dryden is permitted to appear only twice in the Golden Treasury . His songs, to be treated of more fully when we consider the lyrical poetry of the period, though often instinct with true lyrical spirit, seem to have been deliberately composed for insertion in his plays, and the same is the case with almost the whole of what he would have called his occasional poetry. His two chief odes, Alexander’s Feast and the memorial verses to Anne Killigrew, were indubitably commissions; and it is probable that few of the epistles, elegies, dedications, and prologues which form so considerable a portion of his poetical works were composed without some similar inducement. As a whole, this collection is creditable to his powers of intellect, quickness of wit, and command of nervous masculine diction. It is frequently the work of a master, though conceived in the spirit of a journeyman. The adulation of the patron or the defunct is generally fulsome enough; yet some compliments are so graceful that it is difficult not to believe them sincere, as when he apostrophizes the Duchess of Ormond:

‘O daughter of the Rose, whose cheeks unite

The differing titles of the Red and White!

Who heaven’s alternate beauty well display,

The blush of morning and the milky way.’

Or the conclusion of his epistle to Kneller:

‘More cannot be by mortal art exprest,

But venerable age shall add the rest.

For Time shall with his ready pencil stand,

Retouch your figures with his ripening hand,

Mellow your colours, and imbrown the teint,

Add every grace which Time alone can grant;

To future ages shall your fame convey,

And give more beauties than he takes away.’

Or these from the epistle to his kinsman, John Driden, more likely than any of the others to have been the unbought manifestation of genuine regard:

‘O true descendant of a patriot line!

Who while thou shar’st their lustre lendest thine!

Vouchsafe this picture of thy soul to see,

’Tis so far good as it resembles thee.

The beauties to the original I owe,

Which when I miss my own defects I show;

Nor think the kindred Muses thy disgrace;

A poet is not born in every race;

Two of a house few ages can afford,

One to perform, another to record.

Praiseworthy actions are by thee embraced,

And ’tis my praise to make thy praises last.’

The last couplet, excellent in sense, is an example of Dryden’s one metrical defect. He is not sufficiently careful to vary his vowel-sounds.

Dryden’s translations alone would give him a conspicuous place in English literature. The most important, his complete version of Virgil, has been improved upon in many ways, and yet after all it remains true, that ‘Pitt is quoted, and Dryden read.’ Had he never translated Virgil, his renderings or imitations of Juvenal, Horace, and others, would suffice to entitle him to no inconsiderable rank among those who have enriched their native literature from foreign stores. His principle of translation was correct, and accords with that of the greatest of English critics. Coleridge assured Wordsworth that there were only two legitimate systems of metrical translation, strict literality, or compensation carried to its fullest extent. Dryden most probably had not sufficient Latin to be literal; but in any case his genius would have disdained such trammels, not to mention the more prosaic, but not less potent consideration, that what is written for bread must usually be written in haste – a fact which weighed with Dryden when he discontinued rhyme in his tragedies. Thus thrown back on the system of compensation, he has richly repaid his authors for the beauties of which he has bereaved them, by the beauties which he has bestowed – or which, as he maintains, were actually latent in them – and has expressed many of their thoughts with even enhanced energy. He has, in fact, made them write very much as they would have written if they had been English poets of the seventeenth century, and his work is less translation than transfusion. They necessarily appear much metamorphosed from the originals, but the fault is less that of Dryden than of his age. Could he have attempted the same task in our day with equal resources of genius, and on the same principles of workmanship, he would have succeeded much better, for he would have enjoyed more comprehension of the spirit of his originals than was possible in the seventeenth century. The scholarship of that age had not vivified the information which it had amassed; the idealized, but still vital conceptions of the Renaissance had given place to inanimate conventionality; the people of Greece and Rome appeared to the moderns like people in books; and such warm, affectionate contact between the souls of the present and the past as afterwards inspired Shelley’s versions from Homer and Euripides was in that age impossible.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Age of Dryden»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Age of Dryden» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Age of Dryden» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.