Richard Garnett - The Age of Dryden

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Garnett - The Age of Dryden» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Age of Dryden

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Age of Dryden: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Age of Dryden»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Age of Dryden — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Age of Dryden», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Thus anxious thoughts in endless circles roll,

Without a centre where to fix the soul:

In this wild maze their vain endeavours end: —

How can the less the greater comprehend?

Or finite reason reach infinity?

For what could fathom God were more than he.’

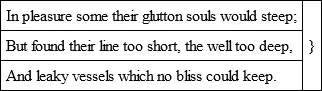

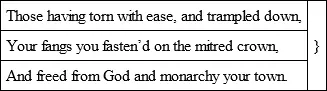

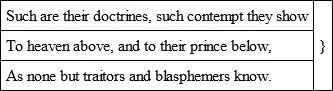

Dryden’s next important poem brought obloquy upon him in his own day, and must be perused with mingled feelings in this. Between 1682 and 1687, the date of the publication of The Hind and the Panther , the laureate of the Church of England had, as we have seen, become a Roman Catholic, and most reasonably desired to justify this step to the world. The Court also expected his pen to be drawn in their service, and hence the double purpose which runs through the poem, of vindicating his personal change of conviction and of justifying the political measures to which James had had recourse for establishing the supremacy of his church. All this was perfectly natural; the extraordinary thing is that so great a master of ridicule should have been blind to the ludicrous character of the machinery which he devised to carry out his purpose. The comparison of the true church to the milk-white hind, and of the corrupt church to the beautiful but spotted panther, might have been employed with propriety as an ornament or illustration of the poem, but the endeavour to make it the groundwork of the entire piece is pregnant with absurdity. Animals may very well be introduced as actors in a fiction upon condition that they behave like animals; and their faculties may even be expanded to suit the author’s purpose so long as their exercise is confined to visible and concrete things; but the notion of a pair of quadrupeds discussing the sacraments, tradition, and the infallibility of the Pope, is only fit for burlesque, and constitutes, indeed, a running burlesque upon the poem. Dryden probably took up the idea without sufficient consideration, and when he had made some progress in his work he may well have been too enamoured with the beautiful but preposterous exordium to surrender it to common sense. Perverse and fantastic as is the plan of his poem, none of his works is richer in beauties of detail. ‘In none,’ says Macaulay, ‘can be found passages more pathetic and magnificent, greater ductility and energy of language, or a more pleasing and various music.’ The power of reasoning in rhyme is little inferior to that displayed in Religio Laici , and the narrative character of the piece allows of a diversified variety excluded by the simply didactic character of its predecessor. The invective against Calvinists and Socinians, typified by the wolf and the fox, is an average, and not beyond an average, example of Dryden’s matchless force. Near the end, it will be perceived, he suddenly bethinks himself that, as the apologist of James’s ostensible policy, it is his business to recommend not persecution but toleration, and he caps his objurgation with a passage conceived in a widely different spirit, a severe though unintentional reflection upon the practice of his own church:

‘O happy pair, how well you have increased!

What ills in church and state have you redress’d!

With teeth, untried, and rudiments of claws,

Your first essay was on your native laws;

What though your native kennel still be small,

Bounded betwixt a puddle and a wall;

Yet your victorious colonies are sent

Where the north ocean girds the continent.

Quicken’d with fire below, your monsters breed

In fenny Holland, and in fruitful Tweed;

And, like the first, the last affects to be

Drawn to the dregs of a democracy.

As, where in fields the fairy rounds are seen,

A rank sour herbage rises on the green;

So, springing where those midnight elves advance,

Rebellion prints the footsteps of the dance.

God, like the tyrant of the skies, is placed,

And kings, like slaves, beneath the crowd debased.

So fulsome is their food, that flocks refuse

To bite, and only dogs for physic use.

As, where the lightning runs along the ground,

No husbandry can heal the blasting wound;

Nor bladed grass, nor bearded corn succeeds,

But scales of scurf and putrefaction breeds;

Such wars, such waste, such fiery tracks of dearth

Their zeal has left, and such a teemless earth.

But, as the poisons of the deadliest kind

Are to their own unhappy coasts confined;

As only Indian shades of sight deprive,

And magic plants will but in Colchos thrive

So presbytery and pestilential zeal

Can only flourish in a commonweal.

From Celtic woods is chased the wolfish crew;

But ah! some pity e’en to brutes is due;

Their native walks, methinks, they might enjoy,

Curb’d of their native malice to destroy.

Of all the tyrannies on human kind,

The worst is that which persecutes the mind.

Let us but weigh at what offence we strike;

’Tis but because we cannot think alike.

In punishing of this, we overthrow

The laws of nations and of nature too.

Beasts are the subjects of tyrannic sway,

Where still the stronger on the weaker prey;

Man only of a softer mould is made,

Not for his fellows’ ruin, but their aid;

Created kind, beneficent and free,

The noble image of the Deity.’

Dryden produced yet one more poem in the interest of the Court, his Britannia Rediviva , an official panegyric on the birth of the Prince of Wales, June, 1688. Literature has perhaps no more signal instance of adulation wasted and prediction falsified. Many lines are spirited, but others betray Dryden’s fatal insensibility to the ridiculous in his own person:

‘When humbly on the royal babe we gaze,

The manly lines of a majestic face

Give awful joy.’

The raptures of the Byzantine courtiers over the imperial infant Protus were nothing to this. Dryden did not want eloquence or dignity to celebrate the hero if he could have found him; it was his and our misfortune that when the hero did at last come to the throne the poet had disqualified himself from extolling him. The landing in Torbay and the triumphal march to London; the victory at the Boyne and the defence of Londonderry were transactions as worthy of epical treatment as any history records; but the only man in England who could have treated them epically deemed them rather matter for elegy; and to have indulged in elegy he must have fled to France. Public events and political and religious controversy were no longer for him: stripped of his means and position he betook himself to translation and playwriting as the readiest means of repairing his shattered fortunes, and it was not until the mellow sunset of his life that he turned to the compositions which, of all he ever wrote, have given the most delight and the least offence, his Fables . These, published at the beginning of 1700, include five adaptations from Chaucer, and three stories told after Boccaccio, as well as Alexander’s Feast , and a few other pieces. It would not be too much to say that this book achieved two things, either of which would have immortalized a poet: it fixed the standard of narrative poetry, except of the metrical romance or ballad class, and also that of heroic versification. The latter, indeed, was thought for a time to have been transcended by Pope, but modern ears have tired of the balanced seesaw of the Popian couplet, and crave the ease and variety of Dryden, restored to literature in Leigh Hunt’s Story of Rimini , and afterwards imitated by Keats in Lamia . The freedom which so great a master allows himself in rhyming should be a lesson to modern purists: final sounds so slightly akin as guard and prepared , placed and last , are of continual occurrence. In matters still more important than versification Dryden is in general equally admirable. He subjected himself to a severe test in competing with Chaucer – severer than he knew, for Chaucer was not yet, even by Dryden, valued at his full worth. In some respects Dryden certainly suffers greatly by the comparison. He is pre-eminently an intellectual poet, to whom the tree of knowledge had been the tree of life; there is perhaps scarcely a thought in his writings that charms by absolute simplicity and pure nature. Wherever, therefore, Chaucer is transparently simple and unaffected, we find him altered for the worse in Dryden. The very important part, however, of The Knight’s Tale which is concerned with courts, camps, and chivalry is even better in Dryden than in his model. He might have defined his sphere in the words of Ariosto, a poet who has many points of contact with him:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Age of Dryden»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Age of Dryden» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Age of Dryden» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.