Richard Garnett - The Age of Dryden

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Garnett - The Age of Dryden» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Age of Dryden

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Age of Dryden: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Age of Dryden»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Age of Dryden — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Age of Dryden», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Let meaner spirits stoop to low precarious fame,

Content on gross and coarse applause to live

And what the dull and senseless rabble give;

Thou didst it still with noble scorn contemn,

Nor wouldst that wretched alms receive,

The poor subsistence of some bankrupt, sordid name:

Thine was no empty vapour, raised beneath,

And formed of common breath,

The false and foolish fire, that’s whisked about

By popular air, and glares awhile, and then goes out;

But ’twas a solid, whole, and perfect globe of light,

That shone all over, was all over bright,

And dared all sullying clouds, and feared no darkening night.’

Oldham’s principal celebrity, however, is derived from his satires. He had the knack of stinging invective, and has been not unjustly compared to Churchill. His Satires on the Jesuits exactly suited the time of the Popish Plot, at present they repel by their one-sidedness. All satire, except that inspired by fancy, is apt to become repulsive by its natural tendency to dwell upon the meanest and lowest aspects of human nature; and this is pre-eminently the case with Oldham, who is always ridiculing or denouncing, always drawing his illustrations from the base and offensive, and seldom diversifies his low matter with an ennobling thought. Yet he evinces so much manly sense, and his style is so nervous, that it is impossible not to admire his vigour, and wish him a more inviting subject. His metre and rhyme frequently stand in need of Dryden’s generous apology:

‘O early ripe! to thy abundant store

What could advancing age have added more?

It might, what Nature never gives the young,

Have taught the smoothness of thy native tongue.

But satire needs not these, and wit will shine

Through the harsh cadence of a rugged line.’

All this notwithstanding, Oldham had the root of the matter in him, and has described, as only a poet could, the ambition, the toil, and the triumph of a poet:

‘’Tis endless, Sir, to tell the many ways

Wherein my poor deluded self I please:

How, when the fancy lab’ring for a birth,

With unfelt throes, brings its rude issue forth:

How, after, when imperfect, shapeless thought

Is, by the judgment, into fashion wrought:

When at first search, I traverse o’er my mind,

None, but a dark and empty void I find:

Some little hints, at length, like sparks break thence,

And glimm’ring thoughts, just dawning into sense:

Confus’d, awhile, the mixt ideas lie

With nought of mark to be discover’d by;

Like colours undistinguish’d in the night,

Till the dusk images mov’d to the light,

Teach the discerning faculty to choose,

Which it had best adopt, and which refuse.

Here rougher strokes, touch’d with a careless dash,

Resemble the first setting of a face:

There finish’d draughts in form more full appear,

And in their justness ask no further care,

Meanwhile, with inward joy, I proud am grown,

To see the work successfully go on;

And prize myself in a creating-power,

That could make something, what was nought before.

Sometimes a stiff unwieldy thought I meet,

Which to my laws, will scarce be made submit:

But when, after expense of pains and time,

’Tis manag’d well, and taught to yoke in rhime,

In triumph, more than joyful warriors would,

Had they some stout and hardy foe subdu’d:

And idly think, less goes to their command,

That makes arm’d troops in well-placed order stand,

Than to the conduct of my words, when they

March in due ranks, are set in just array.

Then straight I grow a strange exalted thing,

And equal in conceit at least a king:

As the poor drunkard, when wine stums his brains,

Anointed with that liquor, thinks he reigns;

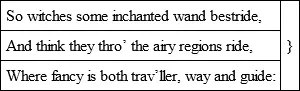

Bewitch’d by these delusions, ’tis I write,

(The tricks some pleasant devil plays in spite)

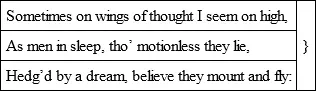

And when I’m in the freakish trance, which I,

Fond silly wretch, mistake for ecstacy,

I find all former resolutions vain,

And thus recant them, and make new again.

“What was’t I rashly vow’d? shall ever I

Quit my beloved mistress, Poetry?

Thou sweet beguiler of my lonely hours,

Which thus glide unperceiv’d, with silent course:

Thou gentle spell, which undisturb’d dost keep

My breast, and charm intruding care asleep:

They say thou’rt poor, and un-endow’d, what tho’?

For thee, I this vain, worthless world forego:

Let wealth and honour be for fortune’s slaves,

The alms of fools, and prize of crafty knaves:

To me thou art, whate’er th’ambitious crave,

And all that greedy misers want or have.

In youth or age, in travel or at home;

Here, or in town, at London, or at Rome;

Rich, or a beggar, free, or in the Fleet,

What’er my fate is, ’tis my fate to write.”’

Oldham’s talent, depending upon masculine sense and vigour of expression rather than upon the more ethereal graces of poetry, was of the kind to expand and mellow by age and practice. Had he lived longer he would undoubtedly have left a name conspicuous in English literature. As it is, he can only be regarded as a bright satellite revolving at a respectful distance around the all-illumining orb of Dryden. Before passing to Marvell and Butler, the only two really original poets after Dryden besides the veterans Cowley and Waller, who belong to the preceding period, it will be convenient to despatch a group of minor bards, whose inclusion in the standard collections of poetry, involving memoirs by a master of biography, has given them more celebrity than they in most instances deserve.

Lord Rochester (1647-1680).

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester (1647-1680), is principally known to posterity by his vices and his repentance. The latter has helped to preserve the memory of the former, which have also left abiding traces in a number of poems not included in his works, and some of which, it may be hoped, are wrongly attributed to him. For a number of years Rochester obtained notoriety as, after Buckingham, the most dissolute character of a dissolute age; but at the same time a critic and a wit, potent to make or mar the fortunes of men of letters. ‘Sure,’ says Mr. Saintsbury, ‘to play some monkey trick or other on those who were unfortunate enough to be his intimates.’ Many a literary cabal was instigated by him, many a libel and lampoon flowed from his pen, among others, The Session of the Poets , correctly characterized by Johnson as ‘merciless insolence.’ Worn out by a life of excess, he died at thirty-three, and his penitence, largely due to the arguments and exhortations of Burnet, afforded the latter material for a narrative which Johnson, entirely opposed as he was to the author’s political and ecclesiastical principles, declares that ‘the critic ought to read for its elegance, the philosopher for its arguments, and the saint for its piety.’

Rochester’s acknowledged poems fall into two divisions of unequal merit. The lyrical and amatory are in general very insipid. The more serious pieces, especially when expressing the discomfort of a sated votary of pleasure, frequently want neither force nor weight. Four particularly fine lines, quoted without indication of authorship in Goethe’s Wahrheit und Dichtung , have frequently occasioned speculation as to their origin. They come from Rochester’s Satyr against Mankind , and read:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Age of Dryden»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Age of Dryden» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Age of Dryden» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.