Christopher Whall - Stained Glass Work - A text-book for students and workers in glass

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher Whall - Stained Glass Work - A text-book for students and workers in glass» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_home, visual_arts, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Fig. 23.

This that you have now, not being a window but a bit of glass to practise on, what I have described above will do for it.

A note to be always industrious and to work with all your might. —I advise you to put this work on an easel; but this is not the way such work is usually done;—where the work is done as a task (alas, that it could ever be so!) it is held listlessly in the left hand while touched with the right; but no artist can afford to be at this disadvantage, or at any disadvantage.

Fancy a surgeon having to hold the limb with one hand while he uses the lancet with the other, or an astronomer, while he makes his measurement, bunglingly moving his telescope by hand while he pursues his star, instead of having it driven by the clock!

You cannot afford to be less keen or less in earnest, and you want both hands free—ay! more than this—your whole body free: you must not be lazy and sit glued to your stool; you must get up and walk backwards and forwards to look at your work. Do you think art is so easy that you can afford to saunter over it?

Do, I beg you, dear reader, pay attention to these words; for it is true (though strange) that the hardest thing I have found in teaching has been to get the pupil to take the most reasonable care not to hamper and handicap himself by omitting to have his work comfortably and conveniently placed and his tools and materials in good order. You shall find a man going on painting all day, working in a messing, muddling way—wasting time and money—because his pigment has not been covered up when he left off work yesterday, and has got dusty and full of "hairs"; another will waste hour after hour, cricking his neck and squinting at his work from a corner, when thirty seconds and a little wit would move his work where he would get a good light and be comfortable; or he will work with bad tools and grumble, when five minutes would mend his tools and make him happy.

An artist's work—any artist's, but especially a glass-painter's—should be just as finished, precise, clean, and alert as a surgeon's or a dentist's. Have you not in the case of these (when the affair has not been too serious) admired the way in which the cool, white hands move about, the precision with which the finger-tips take up this or that, and when taken up use it "just so ," neither more nor less: the spotlessness and order and perfect finish of every tool and material, from those fearsome things which (though you prefer not to dwell on their uses) you cannot help admiring, down to the snowy cotton-wool daintily poked ready through the holes in a little silver beehive? Just such skill, handling, and precision, and just such perfection of instruments, I urge as proper to painting.

What Tools are wanted to complete the Outline. —I will now describe those tools which you want at this stage, that is, to mend your outline with .

Fig. 24.

You want the brush which you used in the first instance to paint it with, and that has already been described; but you also want points of various fineness to etch it away with where it is too thick; these are the needle and the stick (fig. 24); any needle set in a handle will do, but if you want it for fine work, take care that it be sharp. "How foolish," you say; "as if you need tell us that." On the contrary,—nine people out of ten need telling, because they go upon the assumption that a needle must be sharp, "as sharp as a needle," and cannot need sharpening,—and they will go on for 365 days in a year wondering why a needle (which must be sharp) should take out so much coarser a light than they want.

Now as to "sticks"; if you make a point of soft wood it lasts for three or four touches and then gets "furred" at the point, and if of very hard wood it slips on the glass. Bamboo is good; but the best of all—that is to say for broad stick-lights—is an old, sable oil-colour brush, clogged with oil and varnish till it is as hard as horn and then cut to a point; this "clings" a little as it goes over the glass, and is most comfortable to use.

I have no doubt that other materials may be equally good, celluloid or horn, for example; the student must use his own ingenuity on such a simple matter.

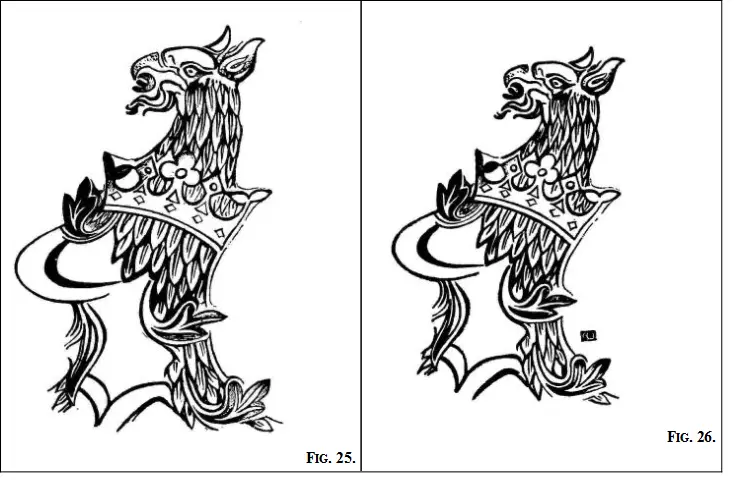

How to Complete the Outline. —With the tools above described complete the outline—by adding colour with the brush where the lines are too fine, and by taking it away with needle or stick where they are too coarse; make it by these means exactly like the copy, and this is all you need do. But as an example of the degree of correctness attainable (and therefore to be demanded) are here inserted two illustrations (figs. 25 and 26), one of the example used, and the other of a copy made from it by a young apprentice.

CHAPTER IV

Matting—Badgering—How to preserve Correctness of Outline—Difficulty of Large Work—Ill-ground Pigment—The Muller—Overground Pigment—Taking out Lights—"Scrubs"—The Need of a Master.

Take your camel hair matting-brush (fig. 27 or 28); fill it with the pigment, try it on the slab of the easel till it seems just so full that the wash you put on will not run down till you have plenty of time to brush it flat with the badger (fig. 29).

Have your badger ready at hand and very clean , for if there is any pigment on it from former using, that will spoil the very delicate operation you are now to perform.

Now rapidly, but with a very light hand, lay an even wash over the whole piece of glass on which the outline is painted; use vertical strokes, and try to get the touches to just meet each other without overlapping; but there is a very important thing to observe in holding the brush. If you hold it so (fig. 30) you cannot properly regulate the pressure, and also the pigment runs away downwards, and the brush gets dry at the point; you must hold it so (fig. 31), then the curve of the hair makes the brush go lightly over the surface, while also, the body of the brush being pointed downwards, the point you are using is always being refilled.

Fig. 27.

Fig. 28.

Fig. 29.

It takes a very skilful workman indeed to put the strokes so evenly side by side that the result looks flat and not stripy; indeed you can hardly hope to do so, but you can get rid of what "stripes" there are by taking your badger and "stabbing" the surface of the painting with it very rapidly, moving it from side to side so as never to stab twice in the same spot; this by degrees makes the colour even, by taking a little off the dark part and putting it on the light; but the result will look mottled, not flat and smooth. Sometimes this may be agreeable, it depends on what you are painting; but if you wish it to be smooth, just give a last stroke or two over the whole glass sideways, that is to say, holding the badger so that it stands quite perpendicular to the glass, move it, always still perpendicular , across the whole surface. You must not sway it from side to side, or kick it up at the end of each stroke like a man white-washing; it must move along so that the points of the hairs are all just lightly touching the glass all the time.

Fig. 30.

How to Ensure the Drawing of a Face being kept Correct while Painting. —If you adopt the plan of doing the first painting over an unfired outline, you must be very careful that the outline is not brushed out of drawing in the process. If you have sufficient skill it need not be so, for it is quite possible—if all the conditions as to adhesiveness are right—and if you are light-handed enough—to so lay and badger the "matt" that the outline beneath shall only be gently softened, and not blurred or moved from its place. But in any case the best plan is at the same time that you trace the outline of a head on to the glass to trace it also with equal care on to a piece of tracing paper, and arrange three or four well-marked points, such as the corner of the mouth, the pupil of the eye, and some point on the back of the head or neck, so that these cannot possibly shift, and that you may be able at any time to get the tracing back into its proper place, both on the cartoon and on the piece of glass on which you are to paint the head. On which piece of glass also your first care should be that these three or four points should be clearly marked and unmovable; then during the whole progress of the painting you will always be able to verify the correctness of the drawing by placing your piece of tracing paper over the glass, and so seeing that nothing has shifted its place.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Stained Glass Work: A text-book for students and workers in glass» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.