Robert DeCourcy Ward - Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert DeCourcy Ward - Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, Физика, foreign_edu, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

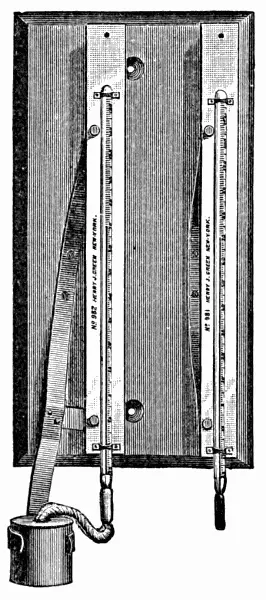

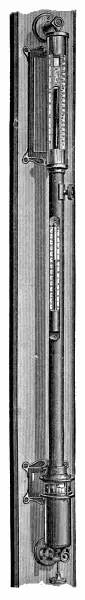

The wet- and dry-bulb thermometers, together commonly known as the psychrometer (Greek: cold measure ), are simply two ordinary mercurial thermometers, the bulb of one of which is wrapped in muslin, and kept moist by means of a wick leading from the muslin cover to a small vessel of water attached to the frame (see Fig. 8). The wick carries water to the bulb just as a lamp wick carries oil to the flame. The psychrometer is seen inside the shelter on the right in Fig. 2.

Fig. 8.

The air always has more or less moisture in it. Even the hot, dry air of deserts contains some moisture. This moisture is either invisible or visible. When invisible it is known as water vapor , and is a gas. When visible, it appears as clouds and fog , or in the liquid or solid form of rain , snow , and hail . The amount of moisture in the air, or the humidity of the air, varies according to the temperature and other conditions. When the air contains as much water vapor as it can hold, it is said to be saturated . Its humidity is then high. When the air is not saturated, evaporation goes on into it from moist surfaces and from plants. Water which changes to vapor is said to evaporate .

This process of evaporation needs energy to carry it on, and this energy often comes from the heat of some neighboring body. When you fan yourself on a very hot day in summer, the evaporation of the moisture on your face takes away some of the heat from the skin, and you feel cooler. The drier the air on a hot day, the greater is the evaporation from all moist bodies, and hence the greater the amount of cooling of the surfaces of those bodies. For this reason a hot day in summer, when the air is comparatively dry, that is, not saturated with moisture, is cooler, other things being equal, than a hot day when the air is very moist. Over deserts the air is often so hot and dry that evaporation from the face and hands is very great, and the skin is burned and blistered. Over the oceans, near the equator, the air is hot and excessively damp, so that there is hardly any cooling of the body by evaporation, and the conditions are very uncomfortable. This region is known as the “Doldrums.”

The temperatures that are felt at the surface of the skin, especially where the skin is exposed, as on the face and hands, have been named sensible temperatures . Our sense of comfort in hot weather depends on the sensible temperatures. These sensible temperatures are not the same as the readings of the ordinary (dry-bulb) thermometer, because our sensation of heat or cold depends very largely on the amount of evaporation from the surface of the body, and the temperature of evaporation is obtained by means of the wet-bulb thermometer. Wet-bulb readings at the various stations of the Weather Bureau are entered on all our daily weather maps. In summer (July) the sensible (wet-bulb) temperatures are 20° below the ordinary air temperature in the dry southwestern portion of the United States (Nevada, Arizona, Utah). The mean July sensible temperatures there are from 50° to 65°; while on the Atlantic coast, from Boston to South Carolina, they are between 65° and 75°. Hence over the latter district the temperatures actually experienced in July average higher than in the former.

Unless the air is saturated with water vapor, the evaporation from the surface of the wet-bulb thermometer will lower the temperature indicated by that instrument below that shown by the dry-bulb thermometer next to it, from which there is no evaporation. The drier the air, the greater the evaporation, and therefore the greater the difference between the readings of the two thermometers. By means of tables, constructed on the basis of laboratory experiments, we may, knowing the readings of the wet and dry-bulb thermometers, easily determine the dew-point and the relative humidity of the air—important factors in meteorological observations (see Chapter XXVI). In winter, when the temperature is below freezing, the muslin of the wet-bulb thermometer should be moistened with water a little while before a reading is to be made. The amount of water vapor which air can contain depends on the temperature of the air. The higher the temperature, the greater is the capacity of the air for water vapor. Hence it follows that, if the temperature is lowered when air is saturated, the capacity of the air is diminished. This means that the air can no longer contain the same amount of moisture (invisible water vapor) as before. Part of this moisture is therefore changed, condensed , as it is said, from the condition of water vapor into that of cloud, fog, rain, or snow. The temperature at which this change begins is called the dew-point of the air.

The relative humidity of the air is the ratio between the amount of water vapor which the air contains at any particular time and the total amount which it could contain at the temperature it then has. Relative humidity is expressed in percentages. Thus, air with a relative humidity of 50% has just half as much water vapor in it as it could hold.

It is found that the readings of the wet-bulb thermometer are considerably affected by the amount of air movement past the bulb, and that in a light breeze, or in a calm, the reading does not give accurate results as to the humidity of the general body of air outside the shelter.

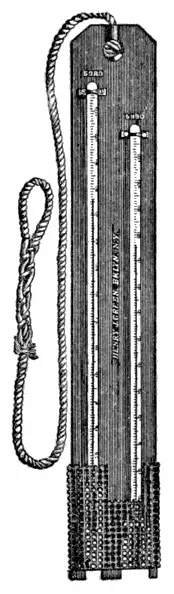

To overcome this difficulty another form of psychrometer has been devised.

The sling psychrometer(Fig. 9) consists simply of a pair of wet and dry-bulb thermometers, fastened together on a board or a strip of metal, to the upper part of which a cord with a loop at the end is attached. In this form of psychrometer there is no vessel of water and no wick, but the muslin cover of the wet-bulb thermometer must be thoroughly wet, by immersion in water, just before each observation. The instrument is then whirled around the hand at the rate of about 12 feet a second. After whirling about 50 times, note the readings, and then whirl the instrument again, and so on, until the wet bulb reaches its lowest reading. The lowest reading of the wet bulb, and the reading of the dry bulb at the same time, are the two observations that should be recorded. Take care to have the muslin wet throughout each observation, and in windy weather stand to leeward of the instrument, so that it may not be affected by the heat of your body. The true reading may be obtained within two or three minutes.

Fig. 9.

Make observations with the wet-bulb thermometer or the sling psychrometer as a part of your regular daily weather record. Note the temperatures indicated by the wet and dry bulbs, and, by means of the table in Chapter XXVI, obtain the dew-point and the relative humidity of the air at each observation. Enter these data in your record book, in a column headed “Humidity,” and subdivided into two columns, one for the dew-point and one for the relative humidity.

Fig. 10.

By means of observations with the psychrometer you will be able to answer such questions as the following:—

Does the relative humidity vary from day to day? Has it any relation to the direction of the wind? To the state of the sky? To precipitation? Does it show any regular variations during the course of a day? How does a high degree of relative humidity affect you in cold weather? In hot weather? Between what limits of percentages does the relative humidity vary? Do the changes come gradually or suddenly? Are these changes related in any way to the changes in the other weather elements? How do the sensible temperatures vary? In what weather conditions do the sensible temperatures differ most from the air temperatures? In what seasons? Compare the sensible temperatures obtained by your own observations with the sensible temperatures at various stations of the Weather Bureau, as given on the daily weather map. Are there any fairly regular differences between the sensible temperatures observed at your own station and the Weather Bureau stations?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Practical Exercises in Elementary Meteorology» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.