John George Wood - Nature's Teachings

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John George Wood - Nature's Teachings» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: foreign_antique, Природа и животные, foreign_edu, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nature's Teachings

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nature's Teachings: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nature's Teachings»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nature's Teachings — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nature's Teachings», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There are many other examples in the animal kingdom, but our limited space will not allow them to be even mentioned.

As to the vegetable examples of this principle, they are so multitudinous that only a very slight description can be given of them.

I suppose that most boys have seen a “cane” (whether they have felt it or not is not to the purpose), and some boys have made sham cigars from pieces of cane. In either case they must have noticed that the cane is not solid, but is pierced with a vast number of holes, passing longitudinally through it, and is, in fact, a collection of little tubes connected and bound together by a common envelope.

The Sugar-cane, if cut across, is seen also to consist of multitudinous cells, which, however, are not hollow, but filled with the sweet liquid from which sugar is obtained by boiling. Then there are many of our common English plants, like the ordinary rush or reed, which are very slight in diameter in comparison with their length, and in which the cells are still further strengthened and lightened by the projection of their sides into a number of points which meet each other, and leave interstices between them. This modification of the cellular system is called “Stellate” (or star-like) Tissue, and two examples of it are given in the illustration, one being taken from the common rush, and the other from the seed-coat of the privet. A very good specimen of stellate tissue may be obtained by cutting a thin section of the white inner peel of the orange.

CHAPTER IV.

SUBSIDIARY APPLIANCES.—Part II

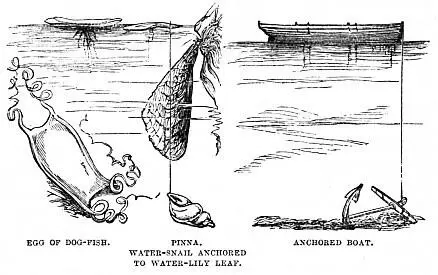

The Cable and its Variations.—Material of Cables.—Hempen and Iron Cables, and Elasticity of the latter.—Natural Cables.—The “Byssus” of the Pinna and the common Mussel.—The Water-snail and its Cable.—A similar Cable produced by the common White Slug.—The Principle of Elasticity.—Elastic Cable of the Garden Spider.—Tendrilous Cables of the Pea and the Bryony.—The Vallisneria, and its Development through the Elastic Cable.—Proposed Submarine Telegraph Cable.—The Anchor, Grapnel, and their Varieties.—Natural Anchors.—Spicule of Synapta.—The Grapnel, natural and artificial.—Ice-anchor and Walrus Tusks.—The Mushroom Kedge.—The Flesh-hook.—Eagle-claw.—The Grapple-plant of South Africa.—The Drag.

AMONG the most important accessories to a ship are the Cable, by which she can be anchored to the bed of the sea, and the ropes called “warps,” by which she can be fastened to the land.

Perhaps my readers may not know the old riddle—“How many ropes are there on board a man-of-war?” The non-nautical individual cannot answer, but the initiated replies that there are only three, namely, the man-rope, the tiller-rope, and the rope’s-end, all the others being “tacks,” “sheets,” “haulyards,” “stays,” “braces,” &c.

Formerly cables were always made of hemp, enormously thick, and most carefully twisted by hand. Now, even in small vessels, the hempen cable has been superseded by the iron chain, and this for several reasons.

In the first place, it is much smaller in bulk, and therefore does not occupy so much room. In the next place, it is even lighter than the hempen cable of corresponding strength; and, in the third, its specific gravity— i.e. its weight when compared with an equal bulk of water—is so great, that when submerged, it falls into a sort of arch-like form, and so attains an elasticity which takes off much of the strain on the anchor, and protects it from dragging.

We will now look to Nature for Cables.

The natural cable which will first suggest itself is evidently that of the Pinna Shell ( Pinna pectinata ), which fixes its shell to some rock or stone with a number of silk-like threads, spun by itself, and protruding from the base, just as a vessel on a lee shore throws out a number of cables. The threads which compose the “byssus,” as it is called, are only a few inches in length, and apparently slight. They are, however, really strong, and by acting in unison enable the shell, though sometimes two feet in length, to be held firmly to the rock. I may here mention that they have been occasionally woven into gloves, and other articles of apparel, to which their natural soft grey-brown hue gives a very pleasing appearance.

A still more familiar instance of a natural marine cable is given by the common Mussel, which can be found in thousands on almost every solid substance which affords it a hold. Even copper-bottomed ships are often covered with Mussels, all clinging by their natural cables, and it is thought that the cases which sometimes occur of being poisoned by eating Mussels, or “musselled,” as the malady is called by the seafaring population, are due to the fact that the Mussels have anchored themselves to copper, and have in consequence imbibed the verdigris.

Passing from salt to fresh water, we come to a natural cable which is very common, and yet, on account of its practical invisibility, is almost unknown, except by naturalists. I refer to the curious cable which is constructed by the common Water-snail ( Limnæa stagnalis ), which has already been mentioned in its capacity of a boat.

This creature has a way of attaching itself to some fixed object, such as a water-lily leaf, by means of a gelatinous thread, which it can elongate at pleasure, and by means of which it can retain its position in a stream, or in still water can sink itself to the bottom, and ascend to the same spot. This cable seems to be made of the same glairy secretion as that which surrounds the egg-masses which are found so plentifully on leaves and stones in our fresh waters, and, like that substance, is all but invisible in the water, so that an inexperienced eye would not be able to see it, even if it were pointed out.

Slight, gelatinous, and almost invisible in the water as is this thread, its strength is very much greater than might be supposed. Not only can a mollusc be safely moored in the water by such a cable, but it can be actually suspended in the air, as may be seen from a letter in Hardwicke’s Science Gossip for 1875, p. 190:—

“Last summer (September 29) I met with the following unusual fact. In a green-house, from a vine-leaf which was within a few inches of the glass … a slug was hanging by a thread, which was more than four feet in length, not unlike a spider-web, but evidently much stronger.

“The slug was descending by means of this thread, and, as the glutinous matter from the under part of the body was drawn out by the weight of the creature, it was consolidated into a compact thread by the slug twisting itself in the direction of the hands of a clock, the power of twisting being given by the head, and the part of the body nearest the head being turned in the direction of the twist. There was no tendency to turn in the contrary direction. Evidently the thread became hard as soon as it was drawn away from the body.

“By wetting the sides of slips of glass, I secured two specimens of the thread. In one of these, part was stretched, and part quite loose, the latter appearing flat when seen through a microscope. The thread, which was highly elastic, was increased about three inches in a minute. The slug was white, and about an inch and a half in length.”

Now we come to the elastic system of the Chain Cable, and find it anticipated in Nature in various ways.

One curious example was that of a Spider, which found its wheel-like net in danger from a tempestuous wind. The Spider descended to the ground, a depth of about seven feet, and, instead of attaching its thread to a stone or plant, fastened it to a piece of loose stick, hauled it up a few feet clear of the ground, and then went back to its web. The piece of stick thus left suspended acted in a most admirable manner, giving strength and support, and at the same time yielding partly to the wind.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nature's Teachings»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nature's Teachings» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nature's Teachings» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.