John George Wood - Nature's Teachings

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John George Wood - Nature's Teachings» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: foreign_antique, Природа и животные, foreign_edu, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nature's Teachings

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nature's Teachings: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nature's Teachings»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nature's Teachings — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nature's Teachings», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

So the reader will see that when engineers found that hollow iron beams were not only lighter, but stronger than solid beams, they were simply copying the hollow beams formed by Nature thousands of years ago.

Another great improvement in ship-building now comes before us.

We have already seen that the earliest boats were merely hollowed logs, just as Robinson Crusoe is represented to have made. But these had many disadvantages. They were always too heavy. They were liable to split, on account of flaws in the wood, and if a large vessel were needed, it was difficult to find a tree sufficiently large, or to get it down to the water when finished.

So the next idea was to build a skeleton, so to speak, of light wooden beams, and to surround it with an outer clothing, or skin, if it may be so termed. As far as I know, the two original types of this structure are the Coracle of the ancient Briton, and the birch-bark Canoe of the North American Indian, and it is not a little remarkable that both exist to the present day, with scarcely any modification.

The Coracle has been already represented on page 22 It is worth while, by the way, to remark how curiously similar are such parallels. I have already mentioned the very evident resemblance between the water-boatman, the water-beetles, and the human rower, the body of the insect being shaped very much like the form of the modern boat. I must now draw the attention of the reader to the similitude between the very primitive boat known by the name of Coracle, and the common Whirlwig-beetle ( Gyrinus natator ), which may be found in nearly every puddle. The shape of the insect is almost identical with that of the boat, and the paddle of the coracle is an almost exact imitation of the swimming legs of the whirlwig. And, as if to make the resemblance closer, many coraclers, instead of using a single paddle with two broad ends, employ two short paddles, shaped very much like battledores.

. It is, perhaps, or was in its original form, the simplest boat in existence, next to the “dug-out.” In the times of the very ancient Britons, who were content with blue paint by way of dress, and lived by hunting and fishing, the Coracle was a basin-shaped basket of wicker-work, rather longer than wide, and covered with the skin of a wild ox. This was sufficiently light to be carried by one man, and sufficiently buoyant to bear him down rapids, if he were a skilful paddler, and, of course, formed a considerable step in civilisation.

The modern Coracle is identical in form, and almost in material. The frame is still oval and basin-shaped, and made of wicker, but the outer covering is not the same. An ox-hide is an expensive article in these days, and, especially when wetted, is very heavy. So the modern Coracle builder covers the wicker skin with a piece of tarpaulin, which is much cheaper than the ox-hide, much lighter, is equally water-tight, and has the great advantage of not absorbing moisture, so that it is as light after use as before.

The Esquimaux make a boat on very similar principles. It is simply hideous in form, resembling a huge washing tub in shape, but, as it is only intended for the inferior beings called women, this does not signify.

Best, most perfect, and most graceful of all such boats is the Birch-bark Canoe of the North American Indians, whose shape has evidently been borrowed from that of a fish. I have seen many of these canoes, and have now before me several models which are exactly like the originals, except in point of size. Instead of being mere elongated bowls, like the coracle, they are long and slender, swelling out considerably in the middle, and coming to an almost knife-like edge at each end. Both stem and stern are alike, so that the canoe can be paddled in either direction, and, as one of the paddlers always acts as steersman, no rudder is needed.

The mode of construction is perfectly simple. The labour is divided between the sexes: the women cut large sheets of bark from the birch-trees, scrape and smooth them, and then sew them together, so as to form the outer skin, or “cloak” as it is called, of the canoe. Meanwhile the men are making the skeleton of strips of white cedar-wood, and binding them into shape with thongs made of the inner bark of the same tree, just like the “bass” of our gardeners. The “cloak” is then gradually worked over the skeleton, sewn into its place, and the canoe is finished. A figure of this canoe, as completed, is given in the same illustration as that which represents various forms of boat, page 7.

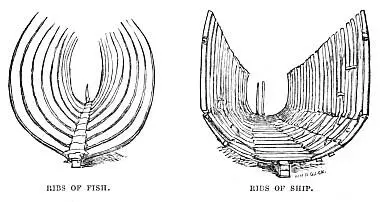

The last improvement is that which was caused by the necessity for large vessels, when planks or iron plates were fastened over the skeleton. But, in all these cases, the vessel is built on the principle of the thorax of a vertebrate animal, that of the whale or a fish being an admirable example. It only needs to take the skeleton of a whale, turn it on its back, and the ribs will be seen to form an almost exact reproduction of those of any ship being built in the nearest dockyard.

I have now before me the spine and ribs of a herring. The fish was over-boiled, and the flesh fell off the bones as it was being lifted out of the dish, leaving most of the ribs in their places. When held with the spine downwards, and viewed from one end, the resemblance to the framework of a ship is absolutely startling, the ribs representing the beams, and the spine taking the place of the keel. I have also before me a sketch representing a section of a Fijian canoe, and it is remarkable that even the very curve of the ribs of the herring is reproduced in those of the canoe.

Whether the Fijians derived this peculiar and beautiful curve from the ribs of a fish I cannot say, but think it very likely.

A still greater improvement in ship-building now comes before us, and this also has been anticipated both in the animal and vegetable kingdoms. There are so many examples of this anticipation that I can only give one or two.

The improvement to which I refer is that which is now almost universally employed in the construction of iron ships, namely, the making the outer shell double instead of single, and dividing it into a number of separate compartments. Putting aside the advantage that if the vessel were stove, only one compartment would fill, we have the fact that the ship is at the same time enormously strengthened and very light in proportion to her bulk.

Perhaps the best, and certainly the most obvious, example of this principle in the animal world is to be found in the skull of the Elephant. The enormous tusks, with their powerful leverage, the massive teeth, and the large and weighty proboscis, require a corresponding supply of muscles, and consequently a large surface of bone for the attachments of these muscles. Now, were the skull solid in proportion to its requisite size, its weight would be too much for the neck to endure, however short and sturdy it might be. The mode of attaining expanse of surface, together with lightness of structure, is singularly beautiful.

Perhaps some of my readers may not be aware that the bone of the skull consists of an outer and inner plate, with a variable arrangement of cells between them. In many animals, such, for example, as man, where the jaws are comparatively feeble, and the teeth small and light, the size of the skull is practically that of the brain, to which it affords a covering. The same structure may be observed in the skull of the common sparrow, where, as in man, the two bony plates are set almost in contact.

But in the elephant these external and internal plates are set widely apart, and the space between them is filled with bony cells, much resembling those of a honeycomb. They are, in fact, just the same cells as those which exist in the skull of man and sparrow, but they are very much enlarged, and in consequence give a large surface, accompanied with united strength and lightness.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nature's Teachings»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nature's Teachings» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nature's Teachings» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.