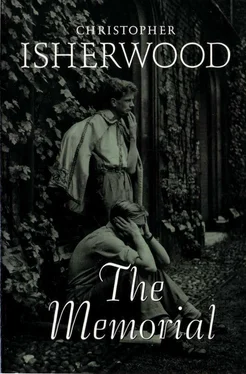

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But he'd suffered enough in exchange. His self-reproaches tortured him. His diary was full of vows that he'd be better, that this miserable bickering should stop. He wildly exaggerated trifles. "Another vile scene this morning," was an entry which recurred. He'd said to himself: What would Father have thought? Father, who'd left her in his charge. Suppose Father were to come back from the grave, suppose it turned out that he'd never been killed, was a shell-shock case, unidentified, in a far-away hospital—and suddenly his memory returned? This was one of Eric's nightmares. Father would come back to find that the two people he loved, who'd once loved each other so much, were leading this sordid, miserable life. Eric thought: But I should shoot myself or die of shame.

And yet this existence continued, did not improve. A horrible facility grew upon them, so that they acquiesced in it. And now it had begun to dawn upon Eric that the suffering was not equally shared. His mother, he now knew, did not feel this friction as he did. Often she'd seem even unaware that what he'd later describe as a "vile scene" was taking place. He detected, with sorrow, a certain hardening and blunting of her sensibilities. She could give a sharp answer without realising that she was quarrelling. And this, a reflection of himself in her, gave him more pain than any other aspect of their relationship.

There had been really serious quarrels, of course. Quarrels leaving half-healed wounds which were daily reopened by sarcasms, trivialities.

One day he'd come in tired and found a strange book lying in his bedroom— Mrs. Eddy. He was in an absurd, resentful mood. He remembered a friend of his mother's whom he disliked, a Miss Prendergast. She lived in the village. All at once he'd seen a vile, a loathsome plot to do a little stealthy propaganda. He'd stalked in to confront his mother:

"How did this book get into my room?"

"What book, darling?"

"This." He tossed it down on the sofa beside her.

She was annoyed at his rudeness. She answered more coldly:

"I suppose I must have left it there by mistake."

"Is it yours?"

"It belongs to Miss Prendergast."

"Then I wish she'd keep it."

"She lent it to me to read," said Lily. "It's very interesting."

Eric burst out in a tone of ferocious mockery:

"I thought you were such a great Protestant."

"That doesn't prevent me from listening to what other people have to say."

"You think people ought to dabble in every Religion?"

"I think people ought to be broad-minded."

"You Protestants aren't very broad-minded about Rome."

" 'You Protestants,' " she couldn't help smiling at this; "why, what are you, darling?"

"It doesn't matter what I am. I'm an ath------"

but he couldn't pronounce the ridiculous word. Turning furiously, he made a violent gesture: "I don't believe in anything."

She took it quite seriously, rather disconcerting him, for he was prepared to meet a sneer.

She answered:

"But surely you don't object to different people seeing the Truth in different ways?"

"You don't understand. I do object. Because it isn't the Truth. I don't just tolerate Religion; I loathe it. All Religion is vile. And religious people are all either hypocrites or idiots."

There! He'd said it, at last. But she only answered with chilly dignity:

"If you feel like that, I can't imagine why you come to church with me on Sundays."

"I come to keep you company," he said. "In future I won't—if you'd rather not."

"I'd much rather you stayed at home."

That was the end of that interview. Later in the evening he'd come in and found her in tears. They had had a reconciliation. He begged forgiveness for his rudeness. They kissed each other. In bed that night, and during the next day, Eric thought over what he had said. And although he was full

of compunction for his treatment of her, and the thought of that quarrel was almost intolerable to him, he couldn't, nevertheless, take back, in his own mind, anything he'd said about Religion. It seemed to him that he had only expressed what had been his conviction for a long time. When next Sunday came round he was prepared, all the same, to go with his mother to church if she asked him to do so. He was sufficiently eager for a complete reconciliation. But Lily didn't ask him. She never asked him again.

Eric turned away from the window, deeply sighed. He was weary—weary to the bone. He was weary of the Hall, of Cambridge, of London, of himself, of everything and everybody. He was too tired to feel unhappy, except by starts. And now he'd got to work. He was always working. He was getting very round-shouldered and his head continually ached. He needed stronger glasses. He knew it and did nothing. There was a certain satisfaction in doing injury to his health and a certain pride in his obstinate, stupid powers of resistance. Other people had nervous breakdowns. He despised them. He knew that, tired out as he was, he'd get through the Trip. He'd get a first. Other people were brilliant and erratic. He just slogged on. He couldn't help it. If he'd gone into the examination-room with the deliberate intention of failing, he couldn't have

brought himself to it—his nature would have revolted. His Tutor had no need to urge him anxiously, as he sometimes did: "Don't overstrain. Don't get stale." He wasn't a neurotic heavyweight boxer. He wouldn't disappoint his backers.

In his first year, Eric had been something of a social success. To be a senior scholar was, after all, a distinction. And for a time he'd lent himself to the atmosphere, gone in for politics, written articles in one of the less frivolous University magazines, occasionally even spoken at the Union, where his measured sentences, carefully avoiding the stammer, had produced an impression. He'd joined a running club and gone for long gruelling runs. Now all that seemed mere waste of time. He'd dropped completely out of College life, become a recluse, the subject of mild jokes.

After all, Eric decided, I'll go. What do I care if he's there or not. It'll make a change. I shall get out of this room for an hour or two, at any rate.

But now I must work, thought Eric, turning wearily to his books and files of notes, sitting down at the table, prodding forward his tired, patient brain, already so overburdened with the loads he had put upon it during the last two years—now I must work.

"Is that you, ducky? Come up," shouted Maurice from the top of the stairs.

He was very smartly dressed and rather conscious of it. Eric didn't like his fashionable little double-breasted waistcoat or his pointed shoes. He'd obviously already had a few drinks:

"I haven't seen you for simply ages."

"Not since last night," Eric smiled.

"I say, did I really see you last night? So I did, of course. What an idiot I am, aren't I?"

"What did you do with the signpost?" Eric asked.

"It's been in the sitting-room. But Mrs. Brown doesn't like it; do you, Mrs. Brown?" For the landlady had appeared with a tray.

"No, indeed I don't, Mr. Scriven. And I hope you'll take the nasty dirty thing away soon. You'll be getting me into trouble."

"Darling Mrs. Brown, yes, of course we'll take it away if you're really sure you don't like it."

Edward Blake was in the sitting-room, with a woman. Eric was rather surprised to recognise her as a painter whom he'd met once or twice at Aunt Mary's last Vac. Her name was Margaret Lanwin. Aunt Mary was having a show of her pictures at the Gallery. She smiled when they shook hands, as much as to say: I expect you're wondering why I'm here. Eric remembered that he had liked her.

"Edward's been showing me a perfectly marvellous new cocktail," said Maurice. "What's it called, Edward?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.