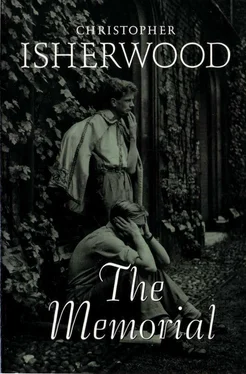

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'' That's not much good to anybody,' 'said Hughes.

"Let's take it back with us," said Maurice.

Amidst roars of laughter, they dug with spanners in the earth, straining now and then at the post. By combined efforts they worked it loose.

"I'm afraid it'll dirty your lovely clean car," said Maurice.

"That doesn't matter a bit," said Currie, who was feeling a tremendous devil.

On the way back to Cambridge, they discussed where it should be put. Maurice's digs was the only possible place. They'd haul it up through the window. It was late. There weren't many people about. Maurice held its head, Farncombe its middle and Hughes its foot. It was wrapped in rugs.

They only met one person—an undergraduate —on the way from the car to the door. As he passed them, Maurice exclaimed:

"Hullo, Eric! Where have you sprung from? I never see you nowadays."

Eric, faintly smiling, very sober, said:

"I've been out to dinner with a don."

"How lovely!" Maurice laughed. "Well, look, darling, when am I going to see you?"

Maurice didn't quite know why he said it. But he never could help giving invitations:

"Look here; come to lunch tomorrow."

Eric seemed about to make some objection.

"You must, see?"

Eric smiled: "Very well. Thank you."

"That's glorious. At half-past one. Edward Blake's going to be there."

They were silent. Eric said :

"What's this you've got?"

Maurice raised a corner of the rug.

"It's the Unknown Warrior. Don't tell the Vice-Chancellor, will you, lovey?"

"No, I won't. Good night."

"Was that your cousin?" Farncombe asked, when Eric had gone.

"Yes."

"He isn't very like you, is he?"

"No," said Maurice, "worse luck. He's the brainiest man in Cambridge."

II

My God, thought Eric, at the window of his large, dark, bare room, looking down into the College Court, where the Tutor was just emerging from a doorway in earnest conversation with the Dean, who wore shorts, dressed for fives; three young men with gowns slung over their shoulders were grouped chatting; a College servant hurried, carrying a pair of boots—how I hate them all!

Standing there, he enclosed, he enfolded them all in his hatred—the discreet funny dons, telling legends about Proust ; the sincere young neurotics, writing each other ten-page notes explaining their conduct at a last night's tiff; the hearties, divided between shop-girls, poker and the C.U.I.C.C.U.; the College servants, so oily in their deference to all these rich young ninnies; the bed-makers, thievish gossipy old hags, who drank as much of their gentlemen's whisky as they dared, and stank so that you could hardly put your nose inside their broom-cupboards after they had gone. And if, at that moment, Eric could have given the order, the

Round Church and the Hall of Trinity and King's Chapel and Corpus Library and dozens of other world-famed architectural lumber-rooms of priceless venerable rubbish would have gone up sky-high with enormous charges of dynamite, and the silk-jumpered young gentlemen and dear old professors been driven out of their well-furnished academic hotels at the point of the bayonet. And Cambridge would have returned to its proper status as a small market-town, inhabited by commercial travellers, auctioneers, cattle-dealers, out-of-work jockeys, and other bar-flies—a soured, defeated tribe, given over to betting and drink, in the middle of this swamp of a country, with rheumatics and damaged lungs. And good riddance, Eric thought.

Well, anyhow, whether I go or not—he knows what I think, Eric reflected. He'd been pretty frank in London last Vac. And Maurice had actually seemed impressed. Yes, Eric, I quite understand. No, I think you're absolutely right. Thanks awfully for telling me.

From anybody else it'd be a deliberate insult. But Maurice never insulted anybody in his life. He couldn't. He was merely being, as usual, quite thoughtless, like a child.

And how sick I am of children,' Eric thought. Everybody up here is a child—a nice, jolly, overgrown boy. All of them artless and kittenish and naive. Maurice does it better than the others. He's more genuine. But I'm sick of the whole push.

Altogether, that visit to London last Vac. had been a most miserable failure. Eric had looked forward to it all through last term. It was to be an escape from Chapel Bridge, from the whole situation at the Hall. He was going to get back into the old Gatesley atmosphere.

He didn't. Aunt Mary's house in the mews seemed to have nothing whatever in common with her other home. And even the Ramsbothams, even Billy Hawkes, seemed preferable to Aunt Mary's new strident friends in their large black hats. Aunt Mary was the same, of course. And so was Anne. But they spoke a new language. They seemed less remarkable; less unique. They had lost power.

Only Maurice, Eric felt, hadn't become, as he put it to himself, a Londoner. Maurice had not suffered from transplantation. And that was why it had seemed worth while saying what he had. He'd been careful, of course, to mention no names. But surely not even Maurice could be so dense— no, there was no way round it, Maurice must have known exactly whom Eric meant.

And here was all the result—an invitation to lunch.

Eric hated the Hall. Sometimes he felt positively suffocated there, as though he'd choke.

"When it's mine," he told Lily, " I shall have it pulled down."

She was not horrified, for she didn't really believe him. Seeing this, he launched into Communistic schemes, quoted Lenin, talked priggishly of the Manchester slums:

"We've no right to live here when all these people are starving."

But she wouldn't argue. He had to go on goading her:

"I know what I shall do. I shall give the land to the Corporation for a model village."

She replied:

"I don't know what I should do if anything happened to the Hall."

She was not attending to what he said, aware only of the tone of his voice and its intention of wounding her. Her listless sadness made him suddenly fierce.

"You care more for this house than you do for human beings."

She only answered, obstinately sad:

"I care for it because it reminds me of the time when I was happy."

And there they were, together in the slowly decaying house, alone to all intents and purposes, for Grandad was now so comatose that you could hardly describe him as alive at all, and Mrs. Potts and Mrs. Beddoes kept their respectful distance— alone, with no Gatesley, no Scrivens, slowly grinding down each other's nerves.

In lucid intervals he even discussed the situation

with her, trying to rationalise, be clinical. He'd glibly generalised: "It's the same with everyone. Parents never get on well with their children. That's just human nature." Had they both at the same instant remembered Aunt Mary? But Lily only sat with moist eyes and shook her head:

"All this is very difficult for me to understand. I don't think my generation felt these things."

"But, Mother, you must see that this can't go on. What are we to do?"

"Darling, you know I only want you to be happy. You must do whatever you think best."

No, she wouldn't help. She surrendered nothing.

But neither do I, Eric admitted to himself.

"You're always arguing," she told him once.

"I hate arguing."

Her gentle, ironic smile. He'd burst out ludicrously :

"I hate arguing, because I'm always in the right."

It was horrible. It became a habit. There was barely a subject they could safely mention. And always, as it seemed to him later, the fault was entirely his. He was crude, overbearing. She was mild and persistent. She seemed barely to argue at all—merely, with an air of distaste, she kept the discussion alive. And in his stammering days, when he'd first begun to lecture her, she'd waited patiently for him while he gasped and mouthed— red with fury at his own impediment.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.