Хорхе Борхес - Collected Fictions

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Хорхе Борхес - Collected Fictions» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1999, ISBN: 1999, Издательство: Penguin (UK), Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Collected Fictions

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin (UK)

- Жанр:

- Год:1999

- ISBN:9780140286809

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collected Fictions: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Collected Fictions»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Collected Fictions — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Collected Fictions», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

while the gods and demiurges had chosen an infinite one: infinite stories, infinitely branching.

Quite unlike April March, yet similarly retrospective, is the heroic two-act comedy The Secret Mirror. In the works we have looked at so far, a formal complexity hobbles the author's imagination; in The Secret Mirror, that imagination is given freer rein. The play's first (and longer) act takes place in the country home of General Thrale, C. I. E., near Melton Mowbray. The unseen center around which the plot revolves is Miss Ulrica Thrale, the general's elder daughter. Snatches of dialog give us glimpses of this young woman, a haughty Amazon-like creature; we are led to suspect that she seldom journeys to the realms of literature. The newspapers have announced her engagement to the duke of Rutland; the newspapers then report that the engagement is off. Miss Thrale is adored by a playwright, one Wilfred Quarles; once or twice in the past, she has bestowed a distracted kiss upon this young man. The characters possess vast fortunes and ancient blood-lines; their affections are noble though vehement; the dialog seems to swing between the extremes of a hollow grandiloquence worthy of Bulwer-Lytton and the epigrams of Wilde or Philip Guedalla. There is a nightingale and a night; there is a secret duel on the terrace. (Though almost entirely imperceptible, there are occasional curious contradictions, and there are sordid details.) The characters of the first act reappear in the second— under different names. The "playwright" Wilfred Quarles is a traveling salesman from Liverpool; his real name is John William Quigley. Miss Thrale does exist, though Quigley has never seen her; he morbidly clips pictures of her out of the Tatler or the Sketch. Quigley is the author of the first act; the implausible or improbable "country house" is the Jewish-Irish rooming house he lives in, transformed and magnified by his imagination.... The plot of the two acts is parallel, though in the second everything is slightly menacing—everything is put off, or frustrated. When The Secret Mirror first opened, critics spoke the names "Freud" and "Julian Green." In my view, the mention of the first of those is entirely unjustified.

Report had it that The Secret Mirror was a Freudian comedy; that favorable (though fallacious) reading decided the play's success. Unfortunately, Quain was over forty; he had grown used to failure, and could not go gently into that change of state. He resolved to have his revenge. In late 1939 he published Statements, perhaps the most original of his works—certainly the least praised and most secret of them. Quain would often argue that readers were an extinct species. "There is no European man or woman," he would sputter, "that's not a writer, potentially or in fact." He would also declare that of the many kinds of pleasure literature can minister, the highest is the pleasure of the imagination. Since not everyone is capable of experiencing that pleasure, many will have to content themselves with simulacra. For those "writers manques" whose name is legion, Quain wrote the eight stories of Statements. Each of them prefigures, or promises, a good plot, which is then intentionally frustrated by the author. One of the stories (not the best) hints at two plots; the reader, blinded by vanity, believes that he himself has come up with them. From the third story, titled "The Rose of Yesterday," I was ingenuous enough to extract "The Circular Ruins," which is one of the stories in my book The Garden of Forking Paths.

1941

[1] So much for Herbert Quain's erudition, so much for page 215 of a book published in 1897. The interlocutor of Plato's Politicus, the unnamed "Eleatic Stranger," had described, over two thousand years earlier, a similar regression, that of the Children of Terra, the Autochthons, who, under the influence of a reverse rotation of the cosmos, grow from old age to maturity, from maturity to childhood, from childhood to extinction and nothingness. Theopompus, too, in his Philippics, speaks of certain northern fruits which produce in the person who eats them the same retrograde growth___Even more interesting than these images is imagining an inversion of Time itself—a condition in which we would remember the Future and know nothing, or perhaps have only the barest inkling, of the Past. Cf. Inferno, Canto X, II. 97-105, in which the prophetic vision is compared to farsightedness.

The Library of Babel

By this art you may contemplate the variation of the 23 letters....

Anatomy of Melancholy, Pt. 2, Sec. II, Mem. IV

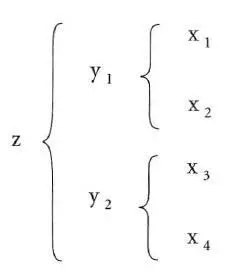

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries. In the center of each gallery is a ventilation shaft, bounded by a low railing. From any hexagon one can see the floors above and below—one after another, endlessly. The arrangement of the galleries is always the same: Twenty bookshelves, five to each side, line four of the hexagon's six sides; the height of the bookshelves, floor to ceiling, is hardly greater than the height of a normal librarian. One of the hexagon's free sides opens onto a narrow sort of vestibule, which in turn opens onto another gallery, identical to the first—identical in fact to all. To the left and right of the vestibule are two tiny compartments. One is for sleeping, upright; the other, for satisfying one's physical necessities. Through this space, too, there passes a spiral staircase, which winds upward and downward into the remotest distance. In the vestibule there is a mirror, which faithfully duplicates appearances. Men often infer from this mirror that the Library is not infinite—if it were, what need would there be for that illusory replication? I prefer to dream that burnished surfaces are a figuration and promise of the infinite.... Light is provided by certain spherical fruits that bear the name "bulbs." There are two of these bulbs in each hexagon, set crosswise. The light they give is insufficient, and unceasing.

Like all the men of the Library, in my younger days I traveled; I have journeyed in quest of a book, perhaps the catalog of catalogs. Now that my eyes can hardly make out what I myself have written, I am preparing to die, a few leagues from the hexagon where I was born. When I am dead, compassionate hands will throw me over the railing; my tomb will be the unfathomable air, my body will sink for ages, and will decay and dissolve in the wind engendered by my fall, which shall be infinite. I declare that the library is endless. Idealists argue that the hexagonal rooms are the necessary shape of absolute space, or at least of our perception of space. They argue that a triangular or pentagonal chamber is inconceivable. (Mystics claim that their ecstasies reveal to them a circular chamber containing an enormous circular book with a continuous spine that goes completely around the walls. But their testimony is suspect, their words obscure. That cyclical book is God.) Let it suffice for the moment that I repeat the classic dictum: The Library is a sphere whose exact center is any hexagon and whose circumference is unattainable.

Each wall of each hexagon is furnished with five bookshelves; each bookshelf holds thirty-two books identical in format; each book contains four hundred ten pages; each page, forty lines; each line, approximately eighty black letters. There are also letters on the front cover of each book; those letters neither indicate nor prefigure what the pages inside will say. I am aware that that lack of correspondence once struck men as mysterious. Before summarizing the solution of the mystery (whose discovery, in spite of its tragic consequences, is perhaps the most important event in all history), I wish to recall a few axioms.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Collected Fictions»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Collected Fictions» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Collected Fictions» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.