Хорхе Борхес - Collected Fictions

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Хорхе Борхес - Collected Fictions» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1999, ISBN: 1999, Издательство: Penguin (UK), Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Collected Fictions

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin (UK)

- Жанр:

- Год:1999

- ISBN:9780140286809

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collected Fictions: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Collected Fictions»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Collected Fictions — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Collected Fictions», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Company, with godlike modesty, shuns all publicity. Its agents, of course, are secret; the orders it constantly (perhaps continually) imparts are no different from those spread wholesale by impostors. Besides—who will boast of being a mere impostor? The drunken man who blurts out an absurd command, the sleeping man who suddenly awakes and turns and chokes to death the woman sleeping at his side—are they not, perhaps, implementing one of the Company's secret decisions? That silent functioning, like God's, inspires all manner of conjectures. One scurrilously suggests that the Company ceased to exist hundreds of years ago, and that the sacred disorder of our lives is purely hereditary, traditional; another believes that the Company is eternal, and teaches that it shall endure until the last night, when the last god shall annihilate the earth. Yet another declares that the Company is omnipotent, but affects only small things: the cry of a bird, the shades of rust and dust, the half dreams that come at dawn. Another, whispered by masked heresiarchs, says that the Company has never existed, and never will. Another, no less despicable, argues that it makes no difference whether one affirms or denies the reality of the shadowy corporation, because Babylon is nothing but an infinite game of chance.

A Survey of the Works of Herbert Quain

Herbert Quain died recently in Roscommon. I see with no great surprise that the Times Literary Supplement devoted to him a scant half column of necrological pieties in which there is not a single laudatory epithet that is not set straight (or firmly reprimanded) by an adverb. The Spectator, in its corresponding number, is less concise, no doubt, and perhaps somewhat more cordial, but it compares Quain's first book, The God of the Labyrinth, with one by Mrs. Agatha Christie, and others to works by Gertrude Stein. These are comparisons that no one would have thought to be inevitable, and that would have given no pleasure to the deceased. Not that Quain ever considered himself "a man of genius"—even on those peripatetic nights of literary conversation when the man who by that time had fagged many a printing press invariably played at being M. Teste or Dr. Samuel Johnson.... Indeed, he saw with absolute clarity the experimental nature of his works, which might be admirable for their innovativeness and a certain laconic integrity, but hardly for their strength of passion. "I am like Cowley's odes," he said in a letter to me from Longford on March 6, 1939. "I belong not to art but to the history of art." (In his view, there was no lower discipline than history.)

I have quoted Quain's modest opinion of himself; naturally, that modesty did not define the boundaries of his thinking. Flaubert and Henry James have managed to persuade us that works of art are few and far between, and maddeningly difficult to compose, but the sixteenth century (we should recall the Voyage to Parnassus, we should recall the career of Shakespeare) did not share that disconsolate opinion. Nor did Herbert Quain. He believed that "great literature" is the commonest thing in the world, and that there was hardly a conversation in the street that did not attain those "heights." He also believed that the aesthetic act must contain some element of surprise, shock, astonishment—and that being astonished by rote is difficult, so he deplored with smiling sincerity "the servile, stubborn preservation of past and bygone books." ... I do not know whether that vague theory of his is justifiable or not; I do know that his books strive too greatly to astonish.

I deeply regret having lent to a certain lady, irrecoverably, the first book that Quain published. I have said that it was a detective story— The God of the Labyrinth; what a brilliant idea the publisher had, bringing it out in late November, 1933. In early December, the pleasant yet arduous convolutions of The Siamese Twin Mystery* gave London and New York a good deal of "gumshoe" work to do—in my view, the failure of our friend's work can be laid to that ruinous coincidence. (Though there is also the question—I wish to be totally honest—of its somewhat careless plotting and the hollow, frigid stiltedness of certain descriptions of the sea.) Seven years later, I cannot for the life of me recall the details of the plot, but this is the general scheme of it, impoverished (or purified) by my forgetfulness: There is an incomprehensible murder in the early pages of the book, a slow discussion in the middle, and a solution of the crime toward the end. Once the mystery has been cleared up, there is a long retrospective paragraph that contains the following sentence: Everyone believed that the chess players had met accidentally. That phrase allows one to infer that the solution is in fact in error, and so, uneasy, the reader looks back over the pertinent chapters and discovers another solution, which is the correct one. The reader of this remarkable book, then, is more perspicacious than the detective.

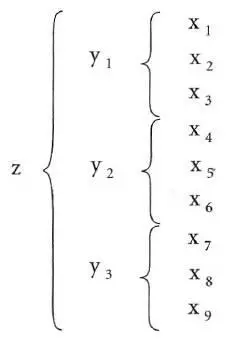

An even more heterodox work is the "regressive, ramifying fiction" April March, whose third (and single) section is dated 1936. No one, in assaying this novel, can fail to discover that it is a kind of game; it is legitimate, I should think, to recall that the author himself never saw it in any other light. "I have reclaimed for this novel," I once heard him say, "the essential features of every game: the symmetry, the arbitrary laws, the tedium." Even the name is a feeble pun: it is not someone's name, does not mean "a march [taken] in April," but literally April-March. Someone once noted that there is an echo of the doctrines of Dunne in the pages of this book; Quain's foreword prefers instead to allude to that backward-running world posited by Bradley, in which death precedes birth, the scar precedes the wound, and the wound precedes the blow (Appearance and Reality, 1897, p. 215). [1] But it is not the worlds proposed by April March that are regressive, it is the way the stories are told—regressively and ramifying, as I have said. The book is composed of thirteen chapters. The first reports an ambiguous conversation between several unknown persons on a railway station platform. The second tells of the events of the evening that precedes the first. The third, likewise retrograde, tells of the events of another, different, possible evening before the first; the fourth chapter relates the events of yet a third different possible evening. Each of these (mutually exclusive) "evenings-before" ramifies into three further "evenings-before," all quite different. The work in its entirety consists, then, of nine novels; each novel, of three long chapters. (The first chapter is common to all, of course.) Of those novels, one is symbolic; another, supernatural; another, a detective novel; another, psychological; another, a Communist novel; another, anti-Communist; and so on. Perhaps the following symbolic representation will help the reader understand the novel's structure:

With regard to this structure, it may be apposite to say once again what Schopenhauer said about Kant's twelve categories: "He sacrifices everything to his rage for symmetry." Predictably, one and another of the nine tales is unworthy of Quain; the best is not the one that Quain first conceived, x 4; it is, rather, x 9, a tale of fantasy. Others are marred by pallid jokes and instances of pointless pseudoexactitude. Those who read the tales in chronological order (e.g., x 3, y 1, z) will miss the strange book's peculiar flavor. Two stories— x 7 and x 8 —have no particular individual value; it is their juxtaposition that makes them effective.... I am not certain whether I should remind the reader that after April March was published, Quain had second thoughts about the triune order of the book and predicted that the mortals who imitated it would opt instead for a binary scheme—

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Collected Fictions»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Collected Fictions» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Collected Fictions» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.