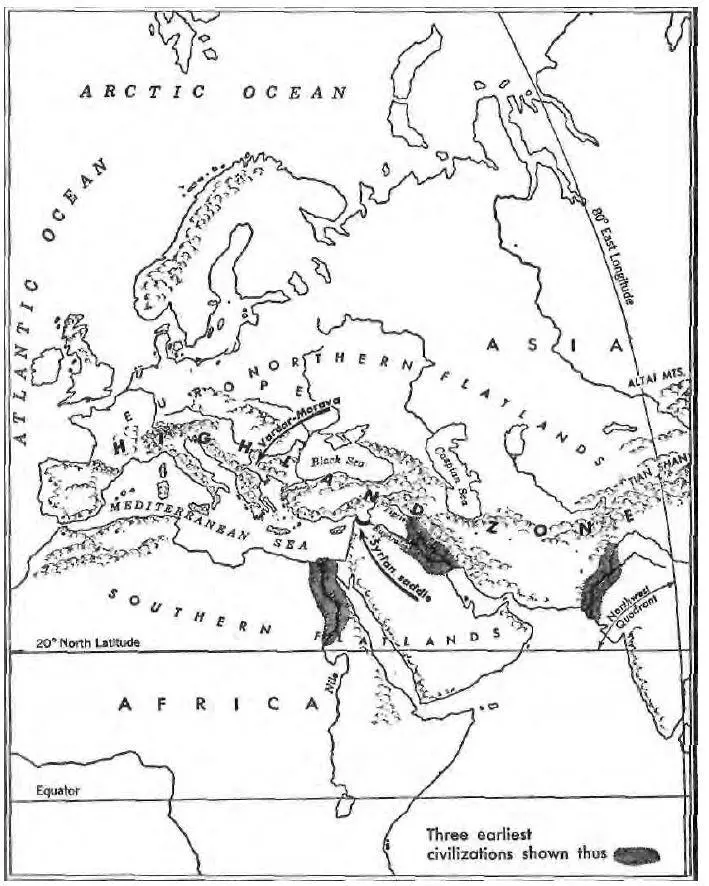

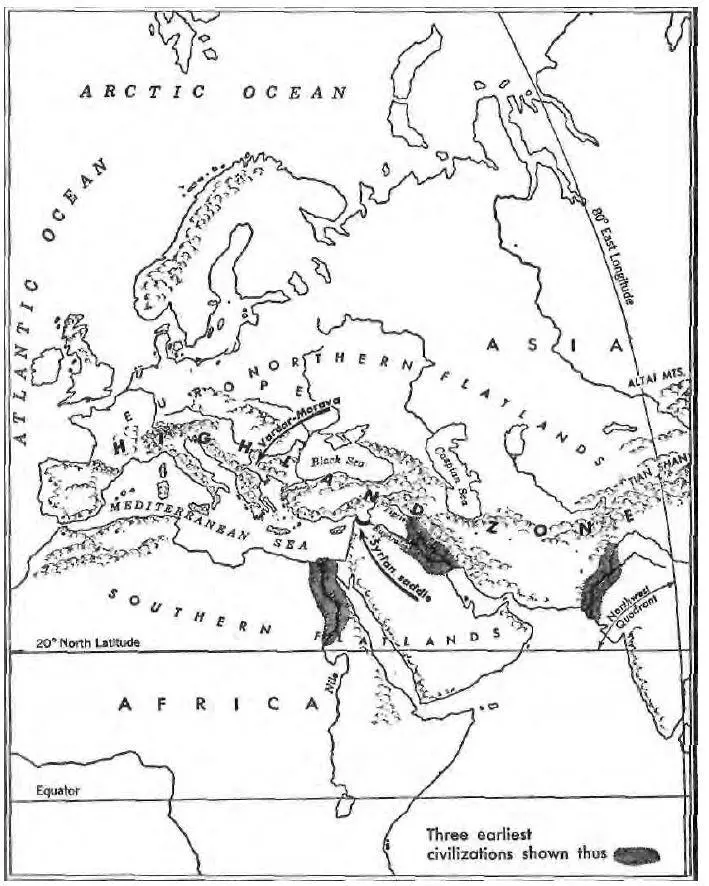

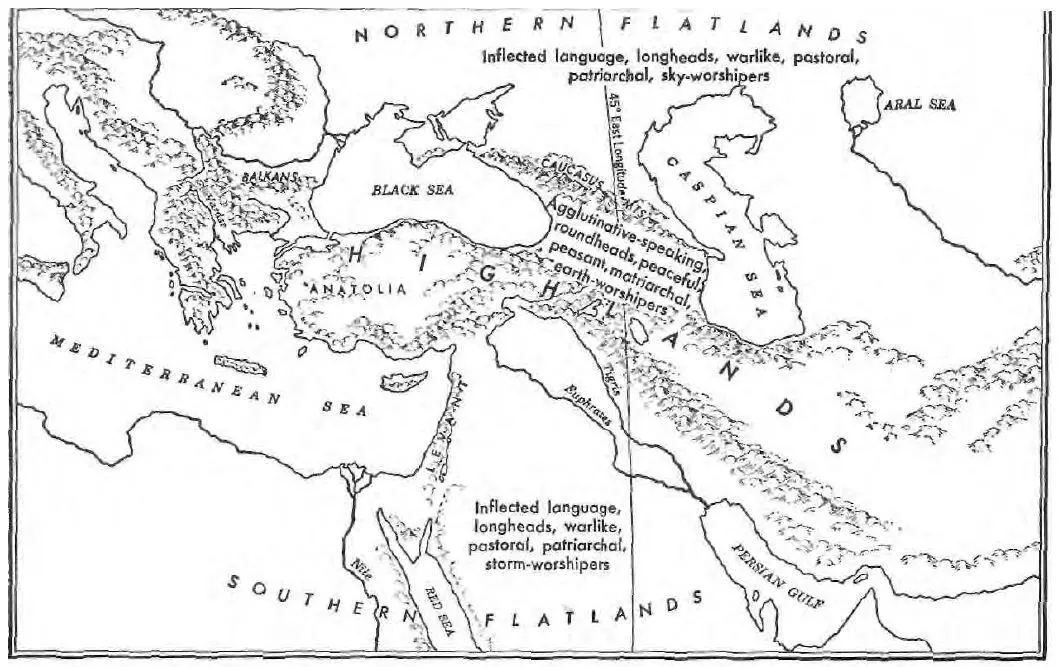

Major geographic features of the Northwest Quadrant (bounded by 20° N. latitude, 80° E. longitude, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Arctic Ocean)

In a similar fashion the Vardar-Morava river valleys provide a route that joins the Aegean Sea near Salonika with the middle Danube. The importance of these two links can be seen in the fact that such significant innovations as metallurgy, alphabetic writing, and Christianity came to Europe by way of the Syrian Saddle and the Mediterranean, while the knowledge of agriculture first came to Europe north of the mountains by way of the Vardar-Morava valley.

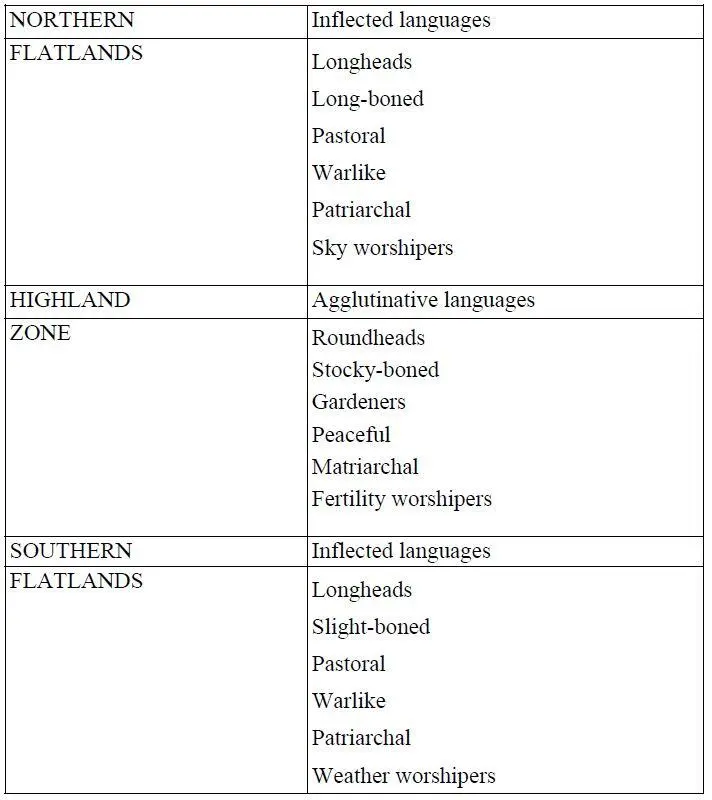

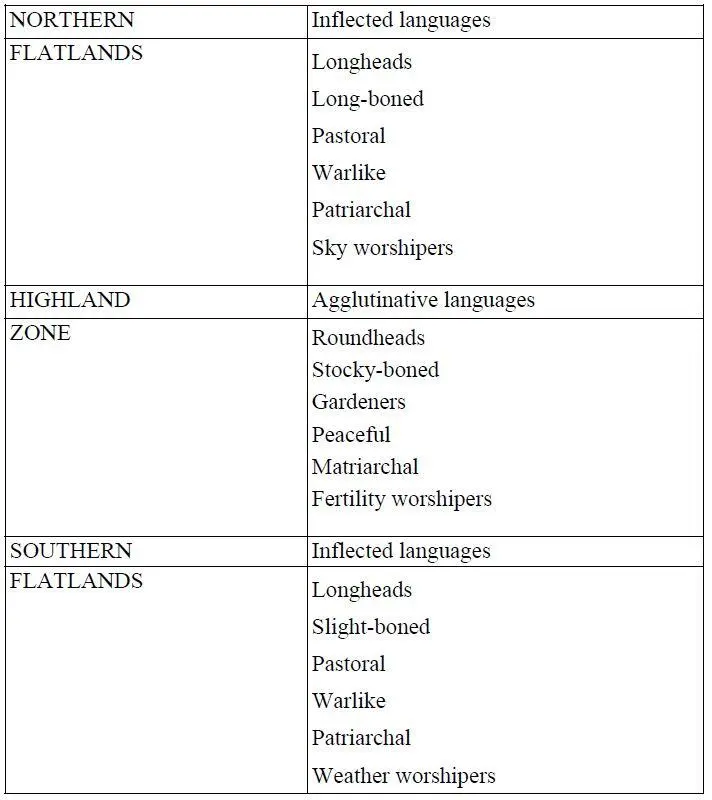

We have already said that the first civilization began in Mesopotamia before 5000 B.C. when people of the Neolithic Garden cultures moved from the Highland Zone down into the alluvial valley and were able to create permanent settlements because of the refertilizing function of the annual floods. These people are known as Sumerians. They were distinguished by two significant features. Physically they were a rather stocky, roundheaded people who seem to have worn closely clipped hair and no beards. And linguistically they spoke an agglutinative language related to Elamite, Hurrian, and other Highland Zone languages but not related either to the inflected Indo-European languages then forming on the Northern Flatlands or to the inflected Semite languages already formed on the Southern Flatlands (Arabia). This difference in language between the Highland Zone peoples and their neighbors in the Flatlands to the north and the south (at least in western Asia) was also reflected in a difference of physical type. The peoples of both Flatlands tended to be longheaded, wore long hair and beards, and were less stocky in bone structure. The peoples of the Southern Flatlands (the Semite speakers) were less tall, and darker in eye, hair color, and complexion than the peoples of the Northern Flatlands (the proto-Indo-European speakers).

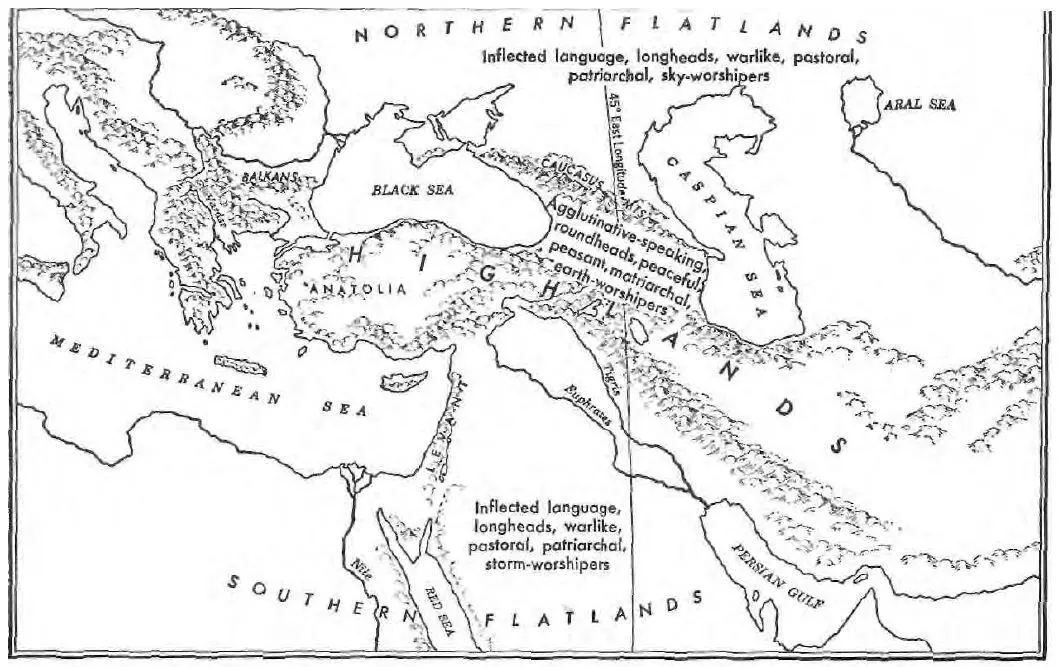

Sandwich distribution of people, languages, and cultures along 45 th meridian East about 3000 B.C.

This sandwichlike arrangement of peoples on the triple-zoned terrain of western Asia seems to have existed when Mesopotamian civilization was first beginning in the centuries before 5000 B.C. and was still in existence two thousand years later (say 3300 B.C.) when the invention of writing and of bronze making marked the shift, at almost the same time, from the prehistoric to the historic period and from the Chalcolithic (or Copper-Stone Age) to the Bronze Age. In fact, the sandwichlike appearance of western Asia was, if anything, increased by 3300 B.C., because by that later date the Highland Zone peoples remained agriculturalists in the double sense we have indicated, while both the Semites to the south and the proto-Indo-Europeans to the north had adopted the care of domestic animals (but not the planting of crops) and had become pastoral peoples. There were other, less dramatic, evidences of this sandwich arrangement. For example, both Flatland dwellers tended to be warlike and patriarchal, and, in religion, emphasized the power of masculine sky gods, while the Highland dwellers tended to be more peaceful, more matriarchal, and had as their chief deity a goddess of fertility and sex who resided in the earth.

This triple pattern of language, physical type, and social customs must not, of course, be made too rigid. A certain amount of mixture and confusion of the pattern must have existed at all times. But there can be no doubt that some such pattern as this did exist on the three-zoned terrain of western Asia along the line of longitude 45° East at the moment when the invention of writing in Mesopotamia marked the advent of the historic period in human history and the clear establishment of the first civilization.

One of the principal tasks of Old World history is to find some explanation of this sandwich pattern of human society at the dawn of history. This can be done to some extent by the triple pattern of geographic terrain, but, while such explanation may be helpful in respect to social customs, it is not completely satisfactory there, and is completely inadequate in explaining the distribution of languages or of physical types of men. Accordingly, explanation based on geographic factors must be supplemented by inferences regarding the events of the prehistoric period before 3000 B.C. In making such inferences we have the evidence supplied by archaeology, but this in turn must be interpreted in terms of the sandwich pattern to be found in the later, historic period. Unfortunately, the areal and chronological specialization of most archaeologists and ancient historians has hampered them in making such inferences or even in realizing the need for them.

Before we present our own inferences on this matter, we should be quite clear what it is that we are seeking to do. We are trying to explain the distribution of languages, physical types, and social customs of western Asia as the matrix in which the earliest, and later, civilizations of that area appeared. Specifically, we wish to explain the pattern of these along the line of 45° East longitude just before 3000 B.C. This pattern can be summed up in the table on page 165. Some of this pattern can be explained in terms of fairly obvious geographic and social factors. The archaeological record shows that the earliest agriculturalists were Highland Zone peoples who had both domestic animals (goats, sheep, and cattle) and crop planting, at a time when the dwellers in both Flatlands were still hunters. The earliest peasants were peaceful because there was a supply of adequately watered land available for occupation by the limited numbers of peasants, without any need to fight for it. Moreover, these earliest gardeners engaged in hoe culture (without plows), which was originally a female activity at a time when males continued to hunt. Later, as the development of sedentary life made hunting dwindle in significance, men became animal tenders, but the food for both the men and their animals was a female product.

Furthermore, the shift from hunting to agriculture provided a rising and more secure standard of living that made possible, as well as desirable, an increase in population. This was also produced by females. The upshot of all this was that the two chief desires of men, that the earth should produce crops and that women should produce offspring, became intellectually confused into a single mystery best summed up in the word "fertility." The reverence and desire for fertility led to a higher social and economic status for women and to the growth of new religious ideas quite different from the animistic religious conceptions of earlier hunting peoples. These new ideas are usually associated with a belief in an earth mother goddess whose confused powers of sexual and agrarian fertility were revered for thousands of years afterward.

The Neolithic Garden cultures were well adapted to the adequately watered hills, parklands, and valleys of the Highland Zone and, with certain modifications, were able to move into alluvial river valleys and across the loess and other semi open areas of Europe and Asia, but they were not able to penetrate the grassy flatlands, both North and South. In many places these flatlands were too arid for neolithic cultures; in more humid regions the grassy sod was too thick to yield to hoe culture; but, above all, most grasslands were inhabited by savage, warlike, hunting peoples struggling for the right to live from the grass-eating herds of the flatlands. In the north these herds were mostly horses and cattle; in the south they were mostly antelope, camels, and asses. In both cases crop planting and the peasant way of life were excluded.

Читать дальше