We could, of course, renounce any desire to deal with the world rationally and content ourselves with successful nonrational dealings with it. We can deal with the irrationality of space, time, quantity, number, race, color, and so forth, simply by action. Merely to walk, or to run like Achilles, is to deal with the irrationality of space and time and to discover, by action, who will win in a race. When we merely walk along, talking with our friends, we are, by walking, dealing successfully with space and time. No one could ever walk rationally. Simply stand still and make an effort to walk rationally. What is the first thing to do? And what should be done next? What messages must be given to which muscles and in what sequence? We do not know, and we could not do such a complicated mental operation quickly enough to walk by any rational thinking process.

When we approach history, we are dealing with a conglomeration of irrational continua. Those who deal with history by nonrational processes are the ones who make history, the actors in it. But the historian must deal with history by rational processes. Accordingly, he must be aware of the processes and difficulties to which we have referred when we try to deal with continua rationally. For history deals with changes in society. And all changes, occurring in time, involve continua. Both society and culture are, even if static, concerned with continua. Indeed, a society is a continuum of continua in five dimensions.

When we say that a society or a civilization exists in five dimensions, we are referring to the fact that it exists in the three dimensions of space, the fourth dimension of time, and the fifth dimension of abstraction. All of these are easy to understand except the last. Let us look, for a moment, at this fifth dimension of abstraction. It is clear that every culture consists of concrete objects like clothes and weapons, of less tangible objects like emotions and feelings, and of quite abstract things like ideas. These form the dimension of abstraction. For example, in Western civilization we have such items as the following: (a) automobiles, (b) romantic love, (c) nationalism, (d) Beethoven's string quartets, and (c) the integral calculus. All of these are clearly products of Western civilization and could not have been produced by any other culture. They are of different degrees of abstractness and, accordingly, we can say that Western culture exists in a fifth dimension, the dimension of abstraction.

This is the same dimensionas the gamut of human needs to which we previously referred. However, it is wider than this gamut. It may be similarly divided into six levels, in a rough and approximate fashion. These divisions are arbitrary and imaginary, and even the order in which we list the levels is partly a matter of taste. These levels are, from the more abstract to the more concrete: (1) intellectual, (2) religious, (3) social, (4) economic, (5) political, and (6) military. Each of them could, if necessary, be subdivided into innumerable sublevels, as, for example, the economic into agriculture, commerce, and industry or into production, distribution and consumption. Such varied divisions and subdivisions are made possible by the fact that the reality is much more subtle and complex than are the categories of our thinking processes.

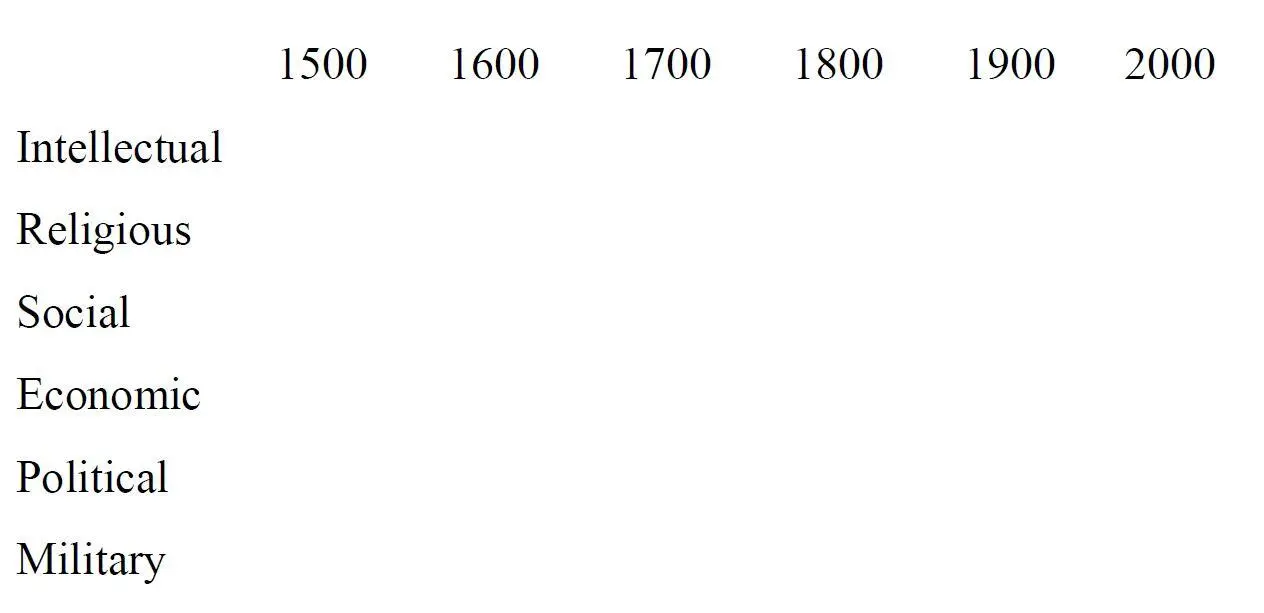

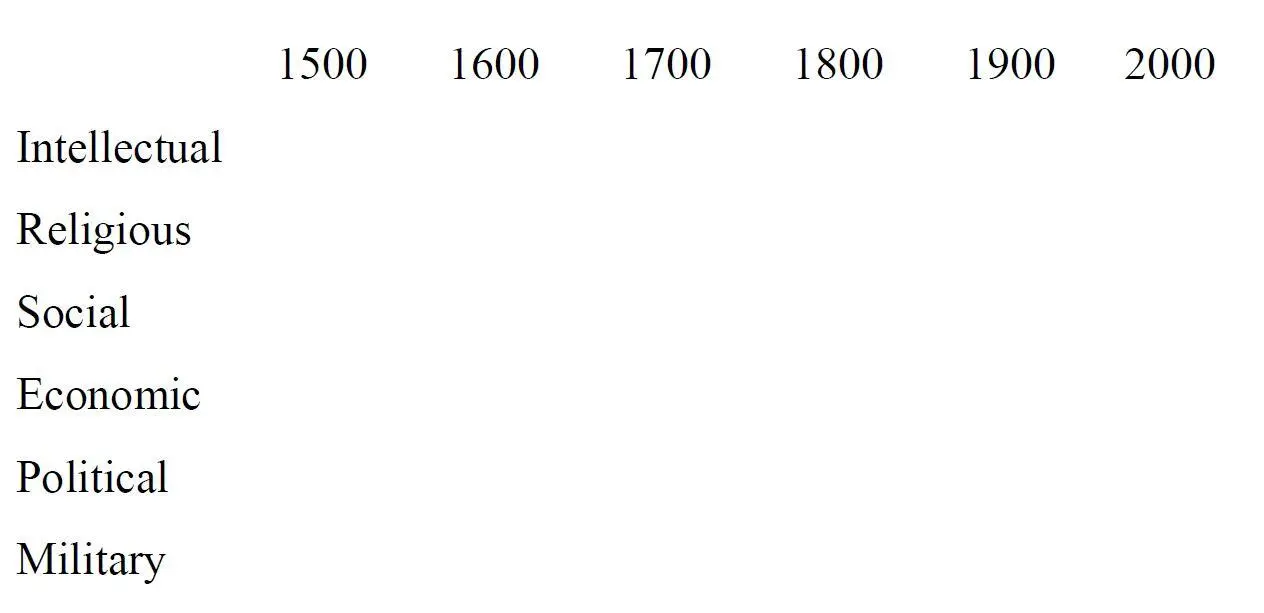

Assuming such a sixfold division of culture, it becomes possible to make a rough diagram of the history of any cultureby letting the vertical axis represent the dimension of abstraction and the horizontal axis (from left to right) represent the passage of time. Thus:

In the above diagram we have represented the changes in culture from 1500 to 2000. The changes that take place in any single level (however we divide it or subdivide it) we shall call "development." Thus we may speak, for example, of the "intellectual development" or of the "military development" of a culture. The process of change on any single level we shall speak of as "historical development" (always remembering that the divisions between levels are arbitrary and imaginary and that we can make as many or as few as we like, because the levels really merge into each other).

Since the levels of culture arise from men's efforts to satisfy their human needs, we can say that every level has a purpose. Assuming the sixfold division we have made, we can speak of six basic human needs: (1) the need for group security, (2) the need to organize interpersonal power relationships, (3) the need for material wealth, (4) the need for companionship, (5) the need for psychological certainty, and (6) the need for understanding. To satisfy these needs, there come into existence on each level social organizations seeking to achieve these. These organizations, consisting largely of personal relationships, we shall call "instruments" as long as they achieve the purpose of the level with relative effectiveness. But every such social instrument tends to become an "institution." This means that it takes on a life and purposes of its own distinct from the purpose of the level; in consequence, the purpose of that level is achieved with decreasing effectiveness. In fact, it can be stated as a rule of history that "all social instruments tend to become institutions." The meaning of this rule will appear as we discuss its causes.

An instrument is a social organization that is fulfilling effectively the purpose for which it arose. An institution is an instrument that has taken on activities and purposes of its own, separate from and different from the purposes for which it was intended. As a consequence, an institution achieves its original purposes with decreasing effectiveness. Every instrument consists of people organized in relationships to one another. As the instrument becomes an institution, these relationships become ends in themselves to the detriment of the ends of the whole organization. When people want their society to be defended, they create an organization called an army. This army consists of many persons with different duties. Each person takes as his purpose the fulfilling of his duties, but this soon leaves no one in the organization with the purpose of the organization as his primary purpose. The purpose of the organization—in this case, to defend the society—becomes no more than a secondary aim for everyone in the organization. Defense becomes secondary to discipline, keeping authority in channels, feeding and paying the troops, providing supplies or intelligence, and keeping visiting congressmen, or the people as a whole, happy about the army, the personal comforts of the soldiers, and so on. Moreover, as a second reason why every instrument becomes an institution, everyone in such an organization is only human and has human weakness and ambitions, or at least has the human proclivity to see things from an egocentric point of view. Thus, in every organization, persons begin to seek their own advancements or to act for their own advantages: seeking promotions, decorations, increases in pay, better or easier assignments; these begin to absorb more and more of the time and energies of the members of an organization. All of this reduces the time and energy devoted to the real goal of the organization and injures the general effectiveness with which an organization achieves its purposes. Finally, as a third reason why every instrument becomes an institution, the social conditions surrounding any such organization change in the course of time. When this happens the organization must be changed to adapt itself to the changed conditions or it will function with decreased effectiveness. But the members of any organization generally resist such change; they have become "vested interests." Having spent long periods learning to do things in a certain way or with certain equipment, they find it difficult to persuade themselves that different ways of doing things with different equipment have become necessary; and, even if they do succeed in persuading themselves, they have considerable difficulty in training themselves to do things in a different way or to use different equipment.

Читать дальше