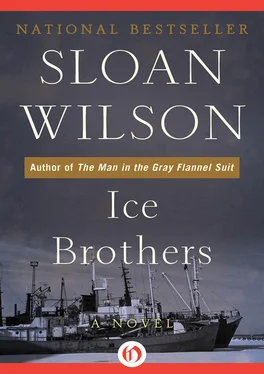

The trawlers were also much more handsome than Paul had expected with the beauty of strength instead of grace. Their high, flared bows looked as though they could punch into the highest seas without danger. Their well deck amidships was only about four feet above the surface of the water, but the sterns were high and handsomely rounded. The only things streamlined about the ships were their short oval smokestacks, which were tilted aft at a rakish angle. They had short stubby masts and heavy freight booms. The ships had been freshly painted with irregular patterns of light blue and white, ice camouflage. There was an air of excitement about them which stemmed from the fact that these little vessels had the ability to live in Arctic seas and ice which would sink thin-skinned destroyers and most of the other ships which towered over them.

The two trawlers were so alike that one resembled a mirror image of the other, but as he walked closer, Paul saw that the inboard vessel already had a stubby cannon on her foredeck, a steel platform for antiaircraft guns amidships and racks of depth charges on the stern which workmen were in the process of adding to the Arluk . Before a wooden gangway that led from the pier to the Nanmak Paul hesitated. There was a whole rigamarole about boarding a Coast Guard or navy ship which he had read about in a copy of the Watch Officers’ Guide , which Chris had given to him and he supposed that he better try it. As he reached the rail of the ship he paused, saluted the quarterdeck (although why he should salute a deck he had no idea), and said to a young seaman who was lounging by the rail, “Request permission to come aboard.”

The seaman looked at him oddly and said, “Come ahead. You want someone aboard here or the Arluk? ”

“The Arluk. ” The decks of the ships were of bright new pine — apparently these vessels had just been built. Picking his way through a tangle of hoses, lines and piles of stores which had not yet been stowed, Paul climbed over the rail to the Arluk . He didn’t bother with saluting the quarterdeck this time, but seeing a short, stout old man in a knitted blue watchcap and a khaki parka, he said, “Permission to come aboard?”

“Why come right ahead,” the man said with a pronounced Maine accent, and his ruddy face broke into a surprisingly sunny, almost childlike smile. “You ain’t our new skipper, be you?”

“I guess I’m supposed to be the executive officer,” Paul said, sounding pompous to himself, and added his name.

“I’m the boatswain — Seth Farmer. We don’t have what you’d call real officers’ quarters aboard here, but I’ll show you your bunk.”

He led the way down a steep companionway near the stern to a dimly lit compartment, all white wood with two bunks on each side and a table in the middle. As they entered, an ensign in his mid-twenties who was lying in the forward, starboard bunk looked up from the book he had been reading. He had a thin, melancholy face, thick glasses and a hooked nose, which gave him an owlish, scholarly appearance.

“This is Mr. Green, our communications officer — he just came aboard about an hour ago,” Farmer said. “Mr. Green, this is Mr. Schuman, our new exec.”

“Pleased,” Green said, and began to climb out of the bunk. Because the deck above the mattress didn’t quite give his tall frame sitting headroom, it was difficult for him to do this gracefully. He bumped his forehead and had difficulty untangling his long legs from a blanket before he stood up, a gaunt, stooped man six feet, two inches tall who had been described as resembling a “Jewish Abe Lincoln.”

“Glad to meet you,” he said, shaking Paul’s hand firmly. “This is my first sea duty. I’m afraid you’ll find I have a hell of a lot to learn.”

“It’s my first day in the Coast Guard,” Paul said with a rueful laugh. “How about you, Mr. Farmer?” He wasn’t quite sure whether to be so formal in the use of names, but the watch officer’s guide had demanded it.

“Well, I wouldn’t say that this is exactly my first sea duty,” Farmer replied, his Maine twang somehow making it obvious that he had spent at least thirty years sailing the oceans of the world, “but I don’t know much about the Coast Gad. I’ve been a fisherman all my life. I sort of came with this vessel, you might say, like the trawl winch. They’re taking off the rest of the fishing gear, but I guess they’re going to leave me aboard.”

“I’m glad that we’ve got somebody who knows what he’s doing,” Paul replied, deciding that honesty must be the best policy. “I’ve been to sea a little, but to tell the truth, I’m just a summer sailor, and I have just about everything to learn about a ship like this.”

Farmer’s smile illuminated his curiously innocent round, ruddy face.

“That’s the way things go in time of war — first you get the job and then you learn how to do it. There will be plenty to keep you busy, but you young fellers look smart enough to catch on fine before long. You want a cup of coffee?”

“That’s just what I want,” Paul said.

“We don’t have a skipper aboard this hooker yet, and we don’t rightly have an engineer, but we got the damnedest, finest cook I ever seen afloat. They say he used to be some kind of a real fancy hotel chef before he joined up, and I believe it. He’s been baking this morning and I can hardly wait to see what he’s going to come up with this time.”

Green said nothing but listened attentively and smiled. As Farmer led the way to the galley in the forecastle, Green followed, hitting his head on the hatch on the way out and laughing ruefully at his own ungainliness.

The forecastle was a low-ceilinged, V-shaped compartment about thirty feet long with three tiers of bunks on each side for the thirty enlisted men who would make up the crew, and a long, V-shaped table in the middle. Around this table about a dozen young seamen now sat, greedily grabbing fresh blueberry muffins from large platters. In the door to the adjoining galley a short man about forty-five years old stood in a white apron. He wore a tall white chef’s hat, which even Paul knew to be outlandish aboard a trawler or a Coast Guard cutter. When he saw the officers he grinned in a curiously obsequious but sly way and in a thick foreign accent said, “What will it be, gentlemen? Blueberry muffins, apple cake or cherry tarts? Don’t tell me. I’ll fix you a selection.”

Without being asked, a seaman poured coffee from a big pot on the table into white mugs for the two ensigns and the warrant boatswain.

“We need more milk, Cookie,” he called.

“Get it yourself,” Cookie replied haughtily as he appeared with a tray of pastries which would have graced the fanciest of restaurants.

“I never seen anything like this aboard any vessel of any description in my whole life,” Farmer marveled as he helped himself to a cherry tart. “Where did you learn to cook like this, Cookie?”

“Where?” Cookie replied, drawing himself up to his full height of five feet, six inches, which bent his chef’s hat against the overhead. “Where did I learn my profession? Why in the best hotels of Switzerland, of course, in the Cordon Bleu in Paris, and at the Ritz-Carlton here in Boston. And after all that, this Coast Guard makes me a third-class cook! ”

“Now don’t you worry about that, Cookie,” Farmer said. “As soon as we get us a skipper aboard here, we’ll all recommend you for a promotion just as quick as the regulations allow. As far as I can see, you ought to be a regular admiral of cooks if they rate them up that high.”

“Thank you, sir,” Cookie replied with an almost Oriental bow. “I shall always try to please.” Still bowing and smiling in his sly, obsequious way, he backed into his galley and disappeared.

Читать дальше