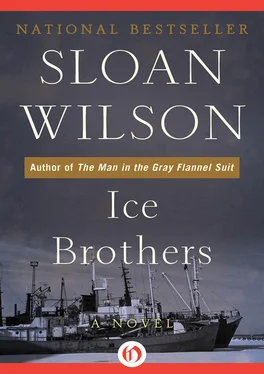

Sloan Wilson

Ice Brothers

A Novel

TO THE MEN OF THE GREENLAND PATROL 1942–1945

Forgotten now and little honored then, but still

They’ll never have to wonder if they’re men.

S.W.

This is fiction based on historical fact. Boston beam trawlers were used by the United States Coast Guard on the Greenland Patrol during World War II. At least one German weather ship was captured by the Coast Guard in Greenland waters. There were many rumors about German weather stations being established on the east coast of Greenland and of German submarines being refueled in the fjords. The author is still not sure how much truth was in them.

I have used the names of real places in this novel, though the characters and their actions are imaginary. The names of the ships except for the Dorchester are also imaginary, although I have made them sound like the Eskimo words which were used by the Coast Guard for trawlers.

Although this is not an autobiographical novel in any narrow sense, I did serve as an ensign aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Tampa on the Greenland Patrol in 1942. A year later I served as executive officer and finally, for a brief time, as commanding officer of the American trawler Nogak on the Greenland Patrol. Our sister ship, the Natsek , was lost with all hands, though near Labrador, not on the east coast of Greenland. The incident of the German officer dropping the liqueur glass was told to me by Gerda Klein, author of “All But My Life.” It happened to her when she was a young girl in Poland in 1939.

The drama in this novel is pure fiction, but I have presented Greenland exactly as I remembered it. It is apparently true that memories of Greenland, like the bodies of people who are buried there, last forever. This book was written in 1979, thirty-six years after I left Greenland, but I did not have to do much research in the libraries.

— Sloan Wilson

CHAPTER 1

The people on Fieldstone Road in Wellesley, Massachusetts, celebrated the bombing of Pearl Harbor with an enormous party. Of course the families there were well aware that war is a terrible thing and they kept saying that to each other, but they were excited, even exalted because hate for a common enemy who is a long way away can make people feel almost ennobled. The radio did not make anything clear, except that the United States had been wantonly attacked and was going to war. “We’re off!” Mark Kettel said, as though the war were a horse race or a long-awaited trip.

The first thing most of the people on Fieldstone Road did was to telephone all their relatives. Families gathered. Neighbors came in, drinks were mixed, and within a few hours the street looked as though a wedding, not a war, were being celebrated in every house.

Paul Schuman drove up to his father-in-law’s house shortly after dark. He had spent that weekend working on his father’s old yawl which was moored off the end of a pier at a deserted shipyard in Quincy. He had not turned on the radio, and at six-thirty that Sunday evening, he was one of the very few people in America who had not heard the big news. Wars between nations were the farthest things from his mind, which was entirely preoccupied with a small, and to him a most mysterious war with his wife, which had caused him to spend a dismal weekend alone. On the drive from Quincy to Wellesley he was trying to make up his mind whether he should just surrender and buy peace with Sylvia at any price, despite the fact that he felt he had been entirely in the right throughout this latest argument.

But wasn’t any man who thought he was entirely in the right during a fight with his wife on dangerous territory? Sylvia was young and pretty and loved parties — certainly he should find no fault with that. Her father was a banker who somehow maintained his modest level of prosperity even in the Depression, and it was hard for her to understand that her young husband didn’t have a dime which he didn’t earn or hustle in some way while trying to get through college. Paul and his brother, Bill, spent a lot of time working on their family’s ancient yawl not just because they loved sailing, but because they were running her as a fairly profitable summer charter boat. And though he was somewhat ashamed of it, Paul spent many evenings playing bridge and poker at fraternity houses and yacht clubs because he had found that it was surprisingly easy for him to make money at cards simply by staying sober.

That all made sense, but the fact remained that Sylvia was not a girl who was accustomed to waiting around home alone, filling her time with vacuuming rugs or reading. She had been going to parties and college dances since her early teens, and as she said, she didn’t think that getting married meant she was supposed to turn into a nun. Her two brothers and Paul’s brother, Bill, often served as her escort when Paul was not available, and what could be wrong with that?

Plenty was wrong with it, Paul reflected darkly, for once she arrived at a party, Sylvia played the familiar part of the belle of the ball as exuberantly as she had before their marriage. He never was sure who brought her home, often in the early hours of the morning, and when he asked questions about what she had been doing, her answers were at best evasive. Her girl friends appeared to be giving a great many very late parties to which no men were invited and there seemed to be a great many very fine old movies which were shown only at midnight.

Paul was a jealous husband and a suspicious one, with or without reason, and he knew that this made him ridiculous, a fact which did not improve his temper. He also worried about his wife because she sometimes drank too much at cocktail parties, and she drove their ancient Ford roadster with the same joyful recklessness which won her so much admiration when she danced. She was, as she boasted, a very skillful driver, just as she was a very good dancer, and this scared him most of all. Sylvia was one of those who just didn’t think accidents could happen, not serious ones, and not to her, anyway.

Sylvia was a handful — her own mother said that, had been saying it for years, and many young men, Paul ruefully thought, had agreed. She was fast and she was wild, had been ever since the age of sixteen, ever since Paul had known her. If he had wanted a nice quiet girl, he should have fallen in love with someone else. He had always known that, but compared to Sylvia, all other women seemed to him to be only half alive.

As she grew older, she would quiet down — he had always been sure of that. And she really wasn’t anywhere near as fast and wild as she liked to pretend and as envious gossips liked to say — he had always been sure of that. Sylvia was Sylvia, and since he could not stop himself from loving her and couldn’t change her, he would have to learn how to live with her in some kind of peace. Lecturing her and trying to lay down the law did not help. The righteous, he had learned, often have to sleep alone.

As he drove through the quiet streets of Wellesley, Paul wished he could buy some flowers as a peace offering for his wife, but all the stores were closed. He needed a gift for her — gifts she always understood better than words, even if they had no real value. Trying to think of something available on a Sunday night, he remembered some new foul weather gear he had bought for the boat at a sale some days before and had left in the trunk of his car. It included a yellow southwester hat, and she always loved headgear of any sort. She would laugh, perch it saucily on the top of her head even if it didn’t fit, and for a little while at least, all their troubles would be forgotten.

Читать дальше