Ben Macintyre - A Spy Among Friends

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ben Macintyre - A Spy Among Friends» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, ISBN: 2014, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Spy Among Friends

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:9781408851746

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Spy Among Friends: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Spy Among Friends»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Spy Among Friends — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Spy Among Friends», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

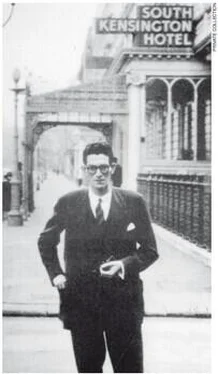

In Berne, Elliott rented a flat on the Dufourstrasse, not far from the British embassy, in which he installed his family, which now included a baby daughter, Claudia. (Elliott had insisted that the baby be born on English soil; had she arrived on her due date, VE Day, 8 May 1945, she would have been christened Victoria Montgomeriana, in patriotic tribute to the British general. Luckily for her, she arrived late.) The baby was the responsibility of ‘Nanny Sizer’, the widow of a sergeant-major, who had enormous feet, drank gin from a bottle labelled ‘Holy Water’ and doubled up as Elliott’s informal bodyguard. Officially, Elliott was second secretary at the British embassy and passport control officer; in reality, at the age of thirty, he was Britain’s chief spy in another espionage breeding ground. In the summer of 1945, after only a few months in post, he was invited to meet Ernest Bevin, the new Foreign Secretary. One of Britain’s earliest Cold Warriors, Bevin remarked over lunch: ‘Communists and communism are vile. It is the duty of all members of the service to stamp upon them at every possible opportunity.’ Elliott never forgot those words, for they mirrored the philosophy he would take into his new role.

*

While Elliott settled in to Switzerland, James Angleton took up residence in neighbouring Italy. In November 1944, the young OSS officer was appointed head of ‘Unit Z’ in Rome, a joint US–UK counter-intelligence force reporting to Kim Philby in London. A few months later, at the age of twenty-seven, he was made chief of X-2 (Counter-espionage) for the whole of Italy, with responsibility for mopping up remaining fascist networks and combating the growing threat of Soviet espionage. With an energy bordering on mania, Angleton set about building a counter-espionage operation of extraordinary breadth and depth. It was said that during the final months of the war he captured ‘over one thousand enemy intelligence agents’ in Italy. Philby kept Angleton supplied with the all-important Bletchley Park decrypts. The American was ‘heavily dependent on Philby for the continuation of his professional success’.

Angleton chatted up priests and prostitutes, ran agents and double agents, and tracked looted Nazi treasures. An ‘enigmatic wraith’ in sharp English tailoring, he ‘haunted the streets of Rome, infiltrating political parties, hiring agents, and drinking with officers of the Italian Secret Service’. At night he was to be found among his files, noting, recording, tracking, plotting, and wreathed in cigarette smoke. ‘You would sit on a sofa across from the desk and he would peer at you through this valley of papers,’ a colleague observed. His fevered approach to his work may have reflected a poetic, if misplaced conviction that he, like Keats, was destined to die of consumption in Rome. He smiled often, but seldom with his eyes. He never seemed to sleep.

Over the coming years, as Soviet intelligence penetrated deeper into Western Europe, James Angleton and Nicholas Elliott worked ever more closely with Philby, the coordinator of Britain’s anti-Soviet operations. Yet the separate sides of Philby’s head created a peculiar paradox: if all his anti-Soviet operations failed, he would soon be out of a job; but if they succeeded too well, he risked inflicting real damage on his adopted cause. He needed to recruit good people to Section IX, but not too good, for these might actually penetrate Soviet intelligence, and discover that the most effective Soviet spy in Britain was their own boss. Jane Archer, the officer who had interrogated Krivitsky back in 1940, joined the section soon after Philby himself. He considered her ‘perhaps the ablest professional intelligence officer ever employed by MI5’, and a serious threat. ‘Jane would have made a very bad enemy,’ he reflected.

As the war ended, a handful of Soviet officials with access to secret information began to contemplate defection, tempted by the attractions of life in the West. Philby was disdainful of such deserters. ‘Was it freedom they sought, or the fleshpots?’ In a way, he, too, was a defector, but he was remaining in place (though enjoying the fleshpots himself). ‘Not one of them volunteered to stay in position and risk his neck for “freedom”,’ he later wrote. ‘One and all, they cut and ran for safety.’ But Philby was haunted by the fear that a Soviet turncoat would eventually emerge with the knowledge to expose him. Here was another conundrum: the better he spied, the greater his repute within Soviet intelligence, and the higher the likelihood of eventual betrayal by a defector.

In September 1945, Igor Gouzenko, a twenty-six-year-old cipher clerk at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, turned up at a Canadian newspaper office with more than a hundred secret documents stuffed inside his shirt. Gouzenko’s defection would be seen, with hindsight, as the opening shot of the Cold War. This trove was the very news Philby had been dreading, for it seemed entirely possible that Gouzenko knew his identity. He immediately contacted Boris Krötenschield. ‘Stanley was a bit agitated,’ Krötenschield reported to Moscow with dry understatement. ‘I tried to calm him down. Stanley said that in connection with this he may have information of extreme urgency to pass to us.’ For the first time, as he waited anxiously for the results of Gouzenko’s debriefing, Philby may have contemplated defection to the Soviet Union. The defector exposed a major spy network in Canada, and revealed that the Soviets had obtained information about the atomic bomb project from a spy working at the Anglo-Canadian nuclear research laboratory in Montreal. But Gouzenko worked for the GRU, Soviet military intelligence, not the NKVD; he knew little about Soviet espionage in Britain, and almost nothing of the Cambridge spies. Philby began to relax. This defector, it seemed, did not know his name. But the next one did.

*

In late August 1944, Chantry Hamilton Page, the vice consul in Istanbul, received a calling card for Konstantin Dmitrievich Volkov, a Soviet consular official, accompanied by an unsigned letter requesting, in very poor English, an urgent appointment. Page discussed this odd communication with the consul, and concluded that it must be a ‘prank’: someone was taking Volkov’s name in vain. Page was still suffering from injuries he had sustained in the bomb attack on the Pera Palace Hotel, and he was prone to memory lapses. He failed to answer the letter, then lost it, and finally forgot about it. A few days later, on 4 September, Volkov appeared at the consulate in person, accompanied by his wife Zoya, and demanded an audience with Page. The Russian couple were ushered into the vice consul’s office. Mrs Volkov was in a ‘deplorably nervous state’, and Volkov himself was ‘less than rock steady’. Belatedly realising that this visit might presage something important, Page summoned John Leigh Reed, first secretary at the embassy and a fluent Russian speaker, to translate. Over the next hour, Volkov laid out a proposal that promised, at a stroke, to alter the balance of power in international espionage.

Volkov explained that his official position at the consulate was cover for his real job, as deputy chief of Soviet intelligence in Turkey. Before coming to Istanbul, he explained, he had worked for some years on the British desk at Moscow Centre. He and Zoya now wished to defect to the West. His motivation was partly personal, a desire to get even after a blazing row with the Russian ambassador. The information he offered was priceless: a complete list of Soviet agent networks in Britain and Turkey, the location of the NKVD headquarters in Moscow and details of its burglar alarm system, guard schedules, training and finance, wax impressions of keys to the files, and information on Soviet interception of British communications. Nine days later Volkov was back, now with a letter laying out a deal.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Spy Among Friends»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Spy Among Friends» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Spy Among Friends» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.