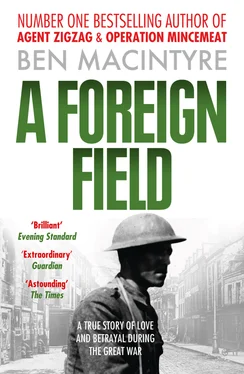

A FOREIGN FIELD

A True Story of Love and Betrayal in the Great War

BEN MACINTYRE

In memory of Angus Macintyre

Title Page A FOREIGN FIELD A True Story of Love and Betrayal in the Great War BEN MACINTYRE

Note on Sources Note on Sources This is a true story. It is based on official documents, letters, diaries, newspaper articles and contemporary writings by the participants. It would have been impossible to tell without the admirable, and peculiarly French, habit of bureaucratic history-hoarding, which prompted local officials to amass quantities of first-hand evidence from ordinary people, describing their experiences in the region behind the lines between 1914 and 1918. This information, collected immediately after the war, was carefully stored in municipal, departmental and academic archives and then almost entirely forgotten. The story has also emerged from hundreds of hours of conversation with scores of people who were directly touched by the events described, or who learned of them from their parents, grandparents and neighbours. Their accounts are inevitably partial, in every sense, but also surprisingly consistent. Recollections of a remote time can never be perfectly accurate, but they were offered with simple honesty and I have tried to record them faithfully. What follows, then, is partly an excavation from a distant war, but also a collective memoir of a community, an attempt to reconstruct a forgotten fragment of the past through reminiscence and oral history.

Prologue

Chapter One - The Angels of Mons

Chapter Two - Villeret, 1914

Chapter Three - Born to the Smell of Gunpowder

Chapter Four - Fugitives

Chapter Five - Behind the Trenches

Chapter Six - Battle Lines

Chapter Seven - Rendezvous

Chapter Eight - Aren’t Those Things Flowers?

Chapter Nine - Sparks of Life

Chapter Ten - The Englishman’s Daughter

Chapter Eleven - Brave British Soldier

Chapter Twelve - Remember Me

Chapter Thirteen - The Somme

Chapter Fourteen - The Wasteland

Chapter Fifteen - Villeret, 1930

EPILOGUE - Villert, 1999

Acknowledgements

Select Bibliography

Notes

About the Author

Also by the Author

Index

Copyright

About the Publisher

This is a true story. It is based on official documents, letters, diaries, newspaper articles and contemporary writings by the participants. It would have been impossible to tell without the admirable, and peculiarly French, habit of bureaucratic history-hoarding, which prompted local officials to amass quantities of first-hand evidence from ordinary people, describing their experiences in the region behind the lines between 1914 and 1918. This information, collected immediately after the war, was carefully stored in municipal, departmental and academic archives and then almost entirely forgotten.

The story has also emerged from hundreds of hours of conversation with scores of people who were directly touched by the events described, or who learned of them from their parents, grandparents and neighbours. Their accounts are inevitably partial, in every sense, but also surprisingly consistent. Recollections of a remote time can never be perfectly accurate, but they were offered with simple honesty and I have tried to record them faithfully. What follows, then, is partly an excavation from a distant war, but also a collective memoir of a community, an attempt to reconstruct a forgotten fragment of the past through reminiscence and oral history.

The glutinous mud of Picardy caked on my shoe-soles like mortar, and damp seeped into my socks as the rain spilled from an ashen sky. In a patch of cow-trodden pasture beside the little town of Le Câtelet we stared out from beneath a canopy of umbrellas at a pitted chalk rampart, the ivystrangled remnant of a vast medieval castle, to which a small plaque had been nailed: ‘Ici ont été fusillés quatre soldats Britanniques.’ Four British soldiers were executed by firing squad on this spot. The band from the local mental institution played ‘God Save the Queen’, excruciatingly, and then someone clicked on a boom box and out crackled a reedy tape-recording of French schoolchildren reciting Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

An honour guard of three old men, dressed in ragged replica First World War uniforms – one English, one Scottish, one French – clutched their toy rifles and looked stern, as the drizzle dripped off their moustaches. A pair of passing cattle stopped on their way to milking and stared at us.

The day before, I had received a call from the local schoolmaster at The Times’s offices in Paris: ‘It would mean a great deal to the village to have a representative of your newspaper present when we unveil the plaque,’ he said. I had hesitated, fumbling for the polite French excuse, but the voice was pressing. ‘You must come, you will find it interesting.’

Reluctantly I set off from Paris, driving up the Autoroute du Nord past signposts – Amiens, Albert, Arras – recalling the First World War, the war to end all wars, and the very worst war, until the one that came after. Following the teacher’s precise directions, I turned off towards Saint-Quentin, across the line of the Western Front, over the River Somme, through land that had once been no-man’s and headed east along a bullet-straight Roman road into the battlefields of the war’s grand finale. No place on earth has been so indelibly brutalised by conflict. The war is still gouged into the landscape, its path traced by the ugly brick houses and uniform churches thrown together with cheap cement and Chinese labour in 1919. It is written in the shape of unexploded shells unearthed with every fresh ploughing and tossed on to the roadside, and in the cemeteries, battalions of dead marching across the fields of northern France in perfect regimental order.

Early for my meeting with the schoolteacher, I stopped beside the British graveyard at Vadancourt and wandered among the neat Commonwealth War Graves headstones with their stock, understated laments for the multitudinous dead: some known, some unknown, and the briskly facile ‘Known Unto God’, one of the many official formulations for engraved grief worked up by Rudyard Kipling. The cemetery is a small one, just a few hundred headstones, a fraction of the 720,000 British soldiers slain, who in turn made up barely one tenth of the carnage of that barbaric war, fought by highly civilised nations for no clear ideological reason.

The schoolteacher, solemn of manner and strongly redolent of lunchtime garlic, was waiting for me by the Croix d’Or restaurant in Le Câtelet, where a group of about thirty people huddled under the eaves, like damp pigeons. I was introduced as ‘Monsieur, le rédacteur du Times,’ an exaggeration of my position that made me suspect he had forgotten my name. My general greeting to the assembled was met with unsmiling curiosity, and again I wondered why I had come to a ceremony for four entirely obscure soldiers, a tiny droplet in the wave of war blood, Known Unto Nobody.

The asylum band, set up in the field behind the restaurant, now broke into a hearty, rhythm-defying rendition of something French and appropriately martial. The three amateur soldiers came to attention, of sorts, as two cars pulled up. Out of the first emerged the mayor of Le Câtelet, the préfet of the region, and his wife; from the second an elderly white-haired woman was extracted, placed in a wheelchair, and trundled across the field to the rampart wall.

Читать дальше