It took less than two minutes for Moon to recount what she’d heard and where she’d heard it, after which she glanced at Commander Forestall’s tablet. “Are the audio files I sent you on that?”

The room listened to a series of whistles and grunts and buzzing sounds, illustrated by a dancing bar graph on the computer screen that rose and fell with the pitch and volume of the sounds.

“That’s a recording of an Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua ,” she said, before opening a second file on the heels of the first. It was hollow, eerie, and haunting. “This one is uguruq bearded seals, recorded from my father’s boat.” She tapped the tablet and a green graph appeared, superimposed over the red lines that depicted the seal song. “Now we add the ice.” The whistles, screams, and chattering groans sounded incredibly human.

She tapped the screen again. “We’ll mute the ice and the biologics, but leave up the visual graphs while we add the recording in question.”

The room sat enthralled by the distinct splash as the hydrophone slipped beneath the surface and the burble as it descended into the deep. A wailing whistle, somewhere in the distance, overlaid significantly with a red graph—the bearded seal. The screech of the ship’s hull against floating ice closely matched the green. Ryan had listened to the file before, but heard it differently now.

The new yellow graph suddenly jumped as new sounds came over the tablet’s tiny speakers. The room sat in rapt silence as the sounds blanked out and then reappeared a few moments later when the hydrophone cable was retrieved.

Ryan took it all in, impressed with the young woman’s forthright demeanor—folksy, from a life lived close to the land, yet bolstered by science.

Moon folded the cover over the tablet screen and gave a somber nod. “This is not fish flatulence, Mr. President, as some of my fellow scientists have suggested. And I do not believe it is ice. I’ve spent my life listening to ice talk and sing. I know what it sounds like.”

Ryan gave a contemplative nod. “I agree.”

Moon’s eyebrows inched up, just a hair, but enough that Ryan noticed. That might be the most emotional outburst he was going to get from this stoic woman.

“It is interesting,” Ryan continued, “that the voices you recorded appeared and then disappeared as the hydrophone went deeper. I’m assuming that you’re working with some sophisticated equipment. I’ve listened to your recording and it sounds almost like the flip of a switch, as if someone turns off the voices and turns them back on again. Why would they not fade away as the hydrophone grew more distant?”

“I’ve thought about that,” Moon said. “There’s still a lot we don’t know about the Arctic Ocean and surrounding seas. For years—decades, really—phantom shoals have appeared on some charts, but not others. One Navy sonar picks up a submerged reef that looks as though it should rip the keel off the ship, while another steams by with nothing between them and the bottom but three hundred fathoms of cold water. Some say these are caused by rising biologics—schools of fish, plankton clouds, even giant squid. Others believe there is a magnetic anomaly and the charts are simply wrong. The point is, Mr. President, the Arctic is a mysterious place. That’s why I’m there, doing what I do. There’s a good chance we’re more familiar with the surface of the moon than we are with what’s down under the ice. Subs are gathering more and more data every day, but it’s a big place, with lots of secrets. What we do know is that the area around the Chukchi Borderland is toothy. There are all sorts of ridges and ledges jutting up from the seabed. A couple of them reach within a few fathoms of the surface. I suspect that whatever … whoever … made the sounds I recorded was located on the opposite side of one of those ridges. Sound waves travel long distances through water, but they are easily attenuated by solid rock, at least as far as my hydrophones are concerned.”

Ryan nodded slowly, picturing the scene.

“So,” he said. “For the sake of illustration, whatever is making voices is on one side of a ridge, say, a hundred meters below the peak, and you lowered your hydrophone on the opposite side. The sounds would be picked up as the hydrophone descended, and then blocked by the underwater mountain when the equipment went below the top, in the rock shadow, so to speak.”

“Exactly, sir,” Moon said.

Forestall put up his hand. “If I may, sir.”

“Go ahead, Robbie.”

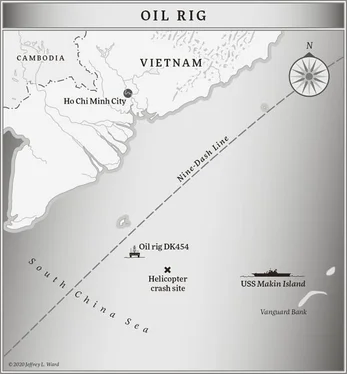

“Given this scenario,” Forestall said, “knowing that the sounds came from the direction of the ridge in relation to the hydrophone, we may be able to triangulate on the signal strength as the instrument descended and the known depth. In theory, that could get us a general location from which the sounds emitted.”

“He’s right,” Dr. Moon said, turning Forestall’s tablet around so Ryan had a good view. The others leaned in. The screen depicted a cross-sectional view of the seabed with the research vessel Sikuliaq on the surface. A series of knifelike ridges rose from the bottom, one almost directly beneath the ship. She tapped the screen and a small box representing the hydrophone appeared beneath the surface. “I began picking up the sounds here,” she said, “as soon as the instrument made it below all the surface clutter—ice, ship noise, et cetera. Then lost it here.”

Foley leaned closer, adjusting her reading glasses. “The hydrophone is still above the ridgetop,” she said. “Not in the shadow yet.”

“Ah,” Dr. Moon said. “But it would be in the shadow if the sounds emanated from this point.” She tapped the screen again, bringing up the red triangle, five hundred feet down, resting on a ledge on the opposite side of the ridge as the hydrophone. “Any sounds coming from here would travel upward, spreading out just enough to allow me to pick them up for a few meters. But if the sounds are coming from here, close to the wall, the shadow starts much higher, before the instrument passes the ridgetop.”

Ryan looked around the room. “Anyone else have questions for Dr. Moon?”

No one did. The matters they had to discuss would take place out of her presence.

“Very well.” Ryan got to his feet. “Thank you for dropping everything for this trip.”

Moon worked her way around the room, shaking hands.

“I wonder,” Ryan said. “Would you mind staying around D.C. for a couple of days?”

“Of course,” she said. “But I’ve already told you everything I know. My field of study is relatively narrow. I’m not sure what help I could offer.”

“You’re smart,” Ryan said, “and you stick up for what you know when peers and superiors try to wave you off. It’s only a request, mind you. If you have something pressing, I understand, but I would appreciate it if you could stay. Commander Forestall will get you set up at the Willard and see that you get a few bucks in per diem.” Ryan walked with her to the door, struck with a sudden idea. “The First Lady is accompanying me to Fairbanks day after tomorrow, where I’m hosting some meetings with the polar nations. You could fly up on Air Force One as my guest, and then I’ll get someone from Wainwright or Eielson to get you back to your ship. If this is what I think it is, things are likely to develop fast, and I’d like to have you around.”

Moon’s brow inched up again. “And what do you think it is, Mr. President?”

Ryan opened the door for her. “The same thing you do. A Chinese submarine that has gotten itself into trouble.”

29

It seemed a simple assignment. Pick three names, one of which would be randomly selected for a suicide mission.

Wan Xiuying sat alone in his quarters, curtain drawn, listening to the terrified sobs of the young crew, smelling the stench of melted metal and the cloyingly sweet odor of cooked flesh. Hunched over his small, fold-out writing desk, the thirty-one-year-old executive officer of the PLAN nuclear ballistic submarine Long March #880 clutched at his forelock with one hand while he tapped his pencil on the blank sheet of paper.

Читать дальше

![Александр Ирвин - Tom Clancy’s The Division 2. Фальшивый рассвет [litres]](/books/417744/aleksandr-irvin-tom-clancy-s-the-division-2-falsh-thumb.webp)