He took a drink of kumis —fermented mare’s milk—and got down to business.

“Forgive me for being forward,” he said. “But I understand you and your wife were in a Chinese detention center in Baijiantan.”

Aisulu leaned forward, grease dripping off her fingers from the beshbarmak . “Someone reported that Kambar was studying Russian. The authorities said that meant we were thinking about leaving China, so they put us in a camp to remind us that the grass is not greener in Kazakhstan.”

Kambar shrugged. “If I am being honest, we were studying Russian so we could leave. Kazakhstan is the best country in the world. No offense meant to Taiwan.”

“What business is that of theirs if we leave China?” his wife snapped. “We are Kazakh. We should be able to come home if we wish.”

“I agree with you,” Yao said. “If I may ask, were you treated harshly in Baijiantan?”

“We were fed,” Kambar said. “Our heads were shaved and I was separated from my wife. We attended many classes, sang songs about the Motherland, told we should love and respect President Zhao, things of that nature. I was not beaten, if that is what you mean, but I saw it happen many times.”

Mrs. Usenov covered her mouth with an open hand as she chewed a large bite of fried dough. She swallowed. “Same for me. But you do not have to be beaten to be mistreated …”

“I am sure,” Yao said. “I would like to return to the conditions inside at another time, perhaps when we are not in the middle of such a delicious meal.”

Kambar looked heavenward while he chewed, remembering. “Though they never beat me, it was the worst time of my life. One day, after two months, they let us go. It took two days, but I was eventually reunited with Aisulu. She was so frail and gaunt, and both of us had terrible coughs—everyone in the camps did.”

“But they came back,” Yao prompted. “The Chinese authorities, and arrested you again?”

Usenov nodded, heaving a great sigh. “I have no idea why. Maybe they needed more numbers for their quota. Maybe they felt they were in error letting us go the first time.”

“But you escaped?”

Mrs. Usenov rocked back and forth on her cushion, excited at the memory. “Kambar and I were in the back of the same van. The van stopped so quickly it threw us all forward. We heard shouting, then gunfire—and then the van began to move again. We drove for a long time, hours maybe. I fell asleep so I do not know.”

“I, too, slept,” Mr. Usenov said, nodding for his wife to continue the story.

“I felt my ears begin to pop, so I knew we were going up into the mountains. I thought maybe they were taking us far away to kill us, but one of the other men said that the Chinese were in charge. If they wanted to kill us, they would not have to drive out of their way to do it. Finally, the van stopped and the doors opened. A man in dark clothing motioned us out, unlocked our shackles, and pointed us toward the Kazakh border.”

“Who rescued you?”

“They wore hoods,” Usenov said. “They did not say it, but I believe they were Wuming.”

“Wuming.” Yao took another drink of fermented mare’s milk.

“You have heard of them?” Mrs. Usenov asked. “They are angels, I think. Allah’s helpers here on earth. Most in the van had thought to grab a blanket or put on a coat. Kambar made sure I had a jacket, but the policeman dragged him out before he could retrieve his own. It was bitter cold, snowing, and Kambar was in his shirtsleeves. One of the Wuming saw this and gave my husband his coat.”

“I would love to interview a member of the Wuming,” Yao said.

Mrs. Usenov exhaled softly. “I do not know how that would happen. Surely that would be much too dangerous for them. The Chinese government would kill them all if they could.”

“That’s true.” Yao shrugged. “They sound like incredibly good people, giving you their own coat.”

“I still have it,” Usenov said proudly. “It is the best coat I have ever owned.” He scrambled to his feet, belying his age. “I will show you.”

Yao wiped his hands with a towel Mrs. Usenov gave him and stood, stepping back from the low table to look at the puffy down ski jacket Kambar Usenov brought out from the bedroom.

“Very nice.” Yao opened it to read the tag, knowing he wouldn’t find a name, but checking nonetheless.

Usenov reached into the pocket and showed him something almost as good.

Yao called Leigh Murphy on his secure mobile.

Excited at the prospect of a lead, he began to speak as soon as she picked up. “Tell me again what Beg said about the woods.”

“Hello to you, too,” Murphy said. “You must have something.”

“Maybe,” Yao said. “So go over Beg’s statement again. The part about the Wuming disappearing.”

“He said they would disappear into the forest, that they could slip over many borders to escape—if they exist at all. Why, what do you have?”

“Not sure,” Yao said. “Maybe nothing. There were some ticket stubs in the pocket of a coat that may have come from a member of the Wuming. They’re only partial stubs, but they’re for a boat tour. It’s something about a monster fish.”

“Lake Kanas?” Murphy said.

“It’s not on the ticket, but I assume the boat tour could be on a lake.”

“The tickets are Chinese, right?” Murphy asked.

“Correct.”

“Then Kanas Lake makes sense,” Murphy said. “They have their own version of the Loch Ness Monster.” She paused.

“You still there?” Yao asked.

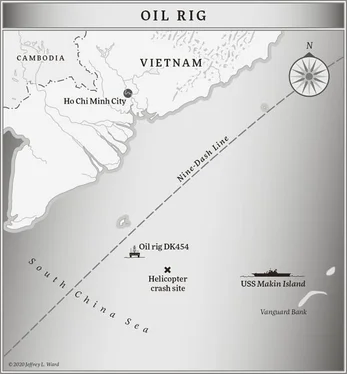

“Yup. Just checking a map. This looks promising, Adam. Lake Kanas is north of Urumqi, tucked into a little thumb of land that is surrounded by Kazakhstan, Russia, and Mongolia … It’s extremely rural, with many borders over which to escape—and lots of forest—just like Urkesh Beg said.”

“That’s thin,” Yao said. “But it’s a hell of a lot more than I had an hour ago. I appreciate this.”

“No prob,” Murphy said. “When are you coming to Albania so I can show you around? We need somebody with a brain to be our station chief. Rask chewed my ass for interviewing Beg without his blessing. I told him I wasn’t allowed to tell him who asked me, which really pissed him off.”

“Sorry about that,” Yao said. “I’ll make a couple of calls and get you top cover. In the meantime, don’t mention the Lake Kanas connection to anyone. Okay?”

“You got it, Chief.”

“Don’t,” Adam said and chuckled. “I’m not chief material.”

“Don’t be a stranger,” Murphy said. “It’s hard to find good friends.”

“In this outfit?”

Murphy sighed. “Anywhere, Adam.”

CIA Station Chief Fredrick Rask hunched over his keyboard, fuming, fingers blazing as he typed a cable. No, this could not be allowed to stand. Leigh Murphy was forgetting her place in the food chain.

A mentor had once told him to get up and go to the restroom before sending a cable or e-mail when you were angry. Good advice, to be sure, if you wanted to be civil, but Rask wanted a piece of somebody’s ass. He was either the station chief or he wasn’t. No one had the right to run an op on his turf without at least letting him know. And he’d be damned if he was going to let some secret-squirrel shithead from Langley sneak into his bailiwick and task one of his case officers without asking his permission. Not to mention the task in question was to chat up the former U.S. detainee about his continued association with Uyghur separatists. The guy had already been interrogated for four and a half years. This kind of shit had the propensity to blow up in your face. The media, Congress, his bosses in D.C.—they’d be all over him if they found out one of his people was harassing a guy they’d let go.

Читать дальше

![Александр Ирвин - Tom Clancy’s The Division 2. Фальшивый рассвет [litres]](/books/417744/aleksandr-irvin-tom-clancy-s-the-division-2-falsh-thumb.webp)