Command wanted the drive and the professor protected if at all possible, but their orders were clear. In the event of an emergency, Long March #880 was not to end up in American—or even Russian—hands. The Mirage drive was Chinese technology, not stolen through tradecraft or purchased from a disgruntled U.S. Navy scientist. It had been developed by China and tested by China, and would eventually be utilized by China. It was a point of national pride—and Beijing wanted it to stay that way.

The self-destruct disks were alarmingly simple to operate. Unlike the nuclear missiles on board, which required the simultaneous use of keys carried by both the captain and the XO to activate the command-and-control system, the self-destruct system could be initiated by the captain alone, or, in his absence, the executive officer.

The captain had met with Wan in private, discussing their options. Tian was no coward. He would detonate the disks if ordered to do so. But he was a patriot and did not want to deprive China of technology that put them ahead in a race that they’d lagged in for so long.

He felt certain command would want to salvage what was left of the drive, and, if possible, nurse Professor Liu back to health. If he destroyed the vessel, the United States would not get it—but, without the professor, China might not be able to re-create it, either.

For years.

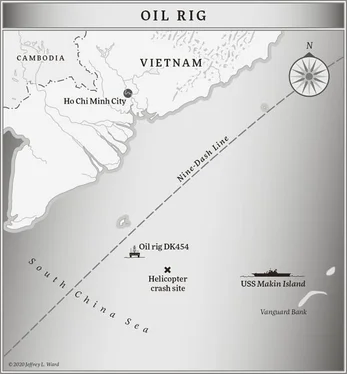

Hydrophones had remained operational. The sonar tech listened to the screws of the surface vessel almost directly overhead. Oblivious to what was occurring five hundred feet below, it departed the area shortly after the accident.

Tian waited four hours, and then, when it became apparent the drive was inoperable, he released the rescue buoy affixed to the exterior of the ship. It was programmed to release after six hours anyway if the timers were not continually reset by each oncoming watch. That way, if all on board were killed in an explosion—or, as in the case of the 61 , died at their stations, China could come and retrieve her submarine.

The distress buoy was attached to the submarine by a long cable that reeled out when it deployed.

Had the buoy made it to the surface, the fleet would have received coded satellite transmissions and then sent someone to rescue the 880 or destroy them. Either way, the captain would have his answer.

But heavy ice had moved in above. The hydrophones picked up the burble of the buoy’s departure, and the unmistakable thud as it impacted the ice. Moving ice tugged at the cable, finally separating it completely and carrying the buoy away without it ever having seen the sky to make its call. A remote underwater autonomous vehicle met the same fate in the unforgiving ice. The Americans had ALSEAMAR SLOT 281s, buoys the size of baseball bats that carried a recorded message to the surface and then scuttled themselves. The 880 was too secret to be equipped with such devices.

The captain decided to try one last option before detonating the self-destruct disks. It was low-tech, and the odds of success were practically nil, but the odds of everyone dying if he did not try were one hundred percent.

He would send a man to the surface.

A torpedo would blast a hole through the ice, hopefully pulverizing a good portion of it. This would almost certainly bring nosy Americans, but he always had the explosive disks as a fallback if that occurred. A volunteer would use the escape trunk to leave the submarine immediately following the fish, rising to the surface in a neoprene escape suit—with a satellite phone in a waterproof bag.

Commander Wan had thought the idea insane, but one did not confide such feelings to a submarine captain. It was either this, the captain had explained, or they all died immediately when the captain initiated the self-destruct mechanism, taking the priceless Mirage drive with them. In time, Wan saw that this was the only way forward—the last way.

And so Wan Xiuying found himself hunched over his desk, clutching his forelock, trying to decide which of his men he would volunteer to climb into the escape trunk, wait for it to fill with water equalizing pressure with the sea, all the while waiting for the horrific banging of the hammer that signaled it was time to open the outer hatch and swim into the cold, dark water … one hundred and seventy meters—five hundred and sixty feet—below the surface.

He used the edge of the desk to carefully tear the paper into three equal pieces—and then wrote his own name on each one.

30

“Your request must be denied out of hand!” Captain Tian snapped, pulling the second, and then the third folded paper out of the cup in Commander Wan’s hand. “I need you here, by my side. These are incredibly important decisions that must be made. If, by some chance, any of us survive this, it should be you. You are the future of our Red Star, Blue Water Navy.”

Wan kept his voice low and even, knowing full well that he would never win an argument with the captain. The man simply did not argue. He would discuss, he would listen to reason, but if for one moment he believed that someone was arguing with him, he would, as the Americans said, pull rank, or, more often than not, simply walk away.

“I understand,” he said. “But if I may, you have said many times that you depend on my counsel. I humbly give you that counsel now. You know how important the Mirage drive is. I am in full agreement with you that if there is any way to save it and Professor Liu, then we should attempt it. Honestly, the chief engineer would have been the best candidate. He was extremely fit, and knew more about the drive than anyone besides the professor. But, sadly, he did not survive the fire. Considering our options dispassionately, I am the next logical choice. I am older than almost any of the submariners, so I am less likely to panic, and in much better physical condition than any of the more mature division chiefs. I swam competitively in secondary school and am a trained scuba diver, accustomed to the water.”

Tian took a long breath, puckering, as if smelling his top lip—it was what he did when he thought and was often copied by the men, though never in his presence.

“This is a suicide mission,” he said. “A one-way trip. No return. One way or another, you will die when you leave this boat. No question about it. In all likelihood, your lungs will rupture during ascent, or you will drown, hopelessly trapped beneath the ice. If you reach the surface alive, there is a better-than-average chance that you will be ground to flotsam by jagged pieces of floating ice. If, by some miracle, you are able to drag your broken body onto the ice and make the call, rescuers may save the ship, but the chances of anyone arriving in time to save you are almost nonexistent.”

“So,” Wan smiled, “there is hope?”

“You will eventually freeze to death.”

“If we do nothing, we all die. It would be my great honor to give my life for the crew and for China.” He shrugged, hoping it looked humble rather than haughty. “And I have heard that dying from cold is not at all unpleasant,” Commander Wan said. “They say one falls asleep.”

“A pleasant way to die indeed, unless your slumber is interrupted by a passing polar bear.” The captain pursed his lips again. “Soviet cosmonauts were issued shotguns to take into space for the eventuality that their capsule landed in Siberia when it returned to earth.” He shivered, trying to shake a memory. “I once saw the body of a man who had been partially eaten by a bear, in Siberia. The beast had broken the poor man’s neck and then eaten his kidneys. I believe he was alive during—”

“With all due respect,” Wan said, smiling, “I would just as soon die as imagine such horrible things.”

The captain took him by both shoulders, tears of pride welling in his eyes, calling him by his given name. “Xiuying, it has been my great honor to serve as your captain …”

Читать дальше

![Александр Ирвин - Tom Clancy’s The Division 2. Фальшивый рассвет [litres]](/books/417744/aleksandr-irvin-tom-clancy-s-the-division-2-falsh-thumb.webp)