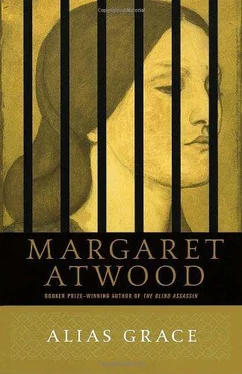

Margaret Atwood - Alias Grace

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Margaret Atwood - Alias Grace» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Alias Grace

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Alias Grace: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Alias Grace»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Alias Grace — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Alias Grace», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He hadn’t expected the collapse of his father, and also of his father’s textile mills — which came first he’s never been sure. Instead of an amusing row down a quiet stream, he’s been overtaken by a catastrophe at sea, and has been left clinging to a broken spar. In other words he has been thrown back on his own resources; which was what, during his adolescent arguments with his father, he claimed to most desire. The mills were sold, and the imposing house of his childhood, with its large staff of domestics — the chambermaids, the kitchen maids, the parlour maids, that ever-changing chorus of smiling girls or women with names like Alice and Effie, who cosseted and also dominated his childhood and youth, and whom he thinks of as having somehow been sold along with the house. They smelled like strawberries and salt; they had long rippling hair, when it was down, or one of them did; it was Effie, perhaps. As for his inheritance, it’s smaller than his mother thinks, and much of the income from it goes to her. She sees herself as living in reduced circumstances, which is true, considering what they have been reduced from. She believes she is making sacrifices for Simon, and he doesn’t want to disillusion her. His father was self-made, but his mother was constructed by others, and such edifices are notoriously fragile. Thus the private asylum is far beyond his reach at present. In order to raise the money for it he would have to be able to offer something novel, some new discovery or cure, in a field that is already crowded and also very contentious. Perhaps, when he has established his name, he will be able to sell shares in it. But without losing control: he must be free, absolutely free, to follow his own methods, once he has decided exactly what they are to be. He will write a prospectus: large and cheerful rooms, proper ventilation and drainage, and extensive grounds, with a river flowing through them, as the sound of water is soothing to the nerves. He’ll draw the line at machinery and fads, however: no electrical devices, nothing with magnets. It’s true that the American public is unduly impressed by such notions — they favour cures that can be had by pulling a lever or pressing a button — but Simon has no belief in their efficacy. Despite the temptation, he must refuse to compromise his integrity. It’s all a pipe dream at present. But he has to have a project of some sort, to wave in front of his mother. She needs to believe that he’s working towards some goal or other, however much she may disapprove of it. Of course he could always marry money, as she herself did. She traded her family name and connections for a heap of coin fresh from the mint, and she is more than willing to arrange something of the sort for him: the horse-trading that’s becoming increasingly common between impoverished European aristocrats and upstart American millionaires is not unknown, on a much smaller scale, in Loomisville, Massachusetts. He thinks of the prominent front teeth and duck-like neck of Miss Faith Cartwright, and shivers.

He consults his watch: his breakfast is late again. He takes it in his rooms, where it arrives every morning, carried in on a wooden tray by Dora, his landlady’s maid-of-all-work. She sets the tray with a thump and a rattle on the small table at the far end of the sitting room, where, once she has gone, he seats himself to devour it, or whatever parts of it he guesses to be edible. He has adopted the habit of writing before breakfast at the other and larger table so he may be seen bent over his work, and will not have to look at her.

Dora is stout and pudding-faced, with a small downturned mouth like that of a disappointed baby. Her large black eyebrows meet over her nose, giving her a permanent scowl that expresses a sense of disapproving outrage. It’s obvious that she detests being a maid-of-all-work; he wonders if there is anything else she might prefer. He has tried imagining her as a prostitute — he often plays this private mental game with various women he encounters — but he can’t picture any man actually paying for her services. It would be like paying to be run over by a wagon, and would be, like that experience, a distinct threat to the health. Dora is a hefty creature, and could snap a man’s spine in two with her thighs, which Simon envisions as greyish, like boiled sausages, and stubbled like a singed turkey; and enormous, each one as large as a piglet.

Dora returns his lack of esteem. She appears to feel that he has rented these rooms with the sole object of causing trouble for her. She fricassees his handkerchiefs and overstarches his shirts, and loses the buttons from them, which she no doubt pulls off routinely. He’s even suspected her of burning his toast and overcooking his egg on purpose. After plumping down his tray, she bellows, “Here’s your food,” as if calling a hog; then she stumps out, closing the door behind her just one note short of a slam. Simon has been spoiled by European servants, who are born knowing their places; he has not yet reaccustomed himself to the resentful demonstrations of equality so frequently practised on this side of the ocean. Except in the South, of course; but he does not go there.

There are better lodgings than these to be had in Kingston, but he doesn’t wish to pay for them. These are suitable enough for the short time he intends to stay. Also there are no other lodgers, and he values his privacy, and the quiet in which to think. The house is a stone one, and chilly and damp; but by temperament — it must be the old New Englander in him — Simon feels a certain contempt for material self-indulgence; and as a medical student he became habituated to a monkish austerity, and to working long hours under difficult conditions.

He turns again to his desk. Dearest Mother, he begins. Thank you for your long and informative letter. I am very well, and making considerable headway here, in my study of nervous and cerebral diseases among the criminal element, which, if the key to them may be found, would go a long way towards alleviating…

He can’t go on; he feels too fraudulent. But he has to write something, or she will assume he has drowned, or died suddenly of consumption, or been waylaid by thieves. The weather is always a good subject; but he can’t write about the weather on an empty stomach.

From the drawer of his desk he takes out a small pamphlet that dates from the time of the murders, and which was sent to him by Reverend Verringer. It contains the confessions of Grace Marks and James McDermott, as well as an abridged version of the trial. At the front is an engraved portrait of Grace, which could easily pass for the heroine of a sentimental novel; she’d been just sixteen at the time, but the woman pictured looks a good five years older. Her shoulders are swathed in a tippet; the brim of a bonnet encircles her head like a dark aureole. The nose is straight, the mouth dainty, the expression conventionally soulful — the vapid pensiveness of a Magdalene, with the large eyes gazing at nothing. Beside this is a matching engraving of James McDermott, shown in the overblown collar of those days, with his hair in a forward-swept arrangement reminiscent of Napoleon’s, and meant to suggest tempestuousness. He is scowling in a brooding, Byronic way; the artist must have admired him. Beneath the double portrait is written, in copperplate: Grace Marks, alias Mary Whitney; James McDermott. As they appeared at the Court House. Accused of Murdering Mr. Thos. Kinnear & Nancy Montgomery. The whole thing bears a disturbing resemblance to a wedding invitation; or it would, without the pictures.

Preparing himself for his first interview with Grace, Simon had disregarded this portrait entirely. She must be quite different by now, he’d thought; more dishevelled; less self-contained; more like a suppliant; quite possibly insane. He was conducted to her temporary cell by a keeper, who’d locked him in with her, after warning him that she was stronger than she looked and could give a man a devilish bite, and advising him to call for help if she became violent.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Alias Grace»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Alias Grace» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Alias Grace» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.