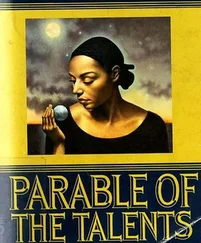

Butler, Octavia - Parable of the Sower

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Butler, Octavia - Parable of the Sower» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Parable of the Sower

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Parable of the Sower: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Parable of the Sower»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Parable of the Sower — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Parable of the Sower», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Should we let her stay?” I asked them.

Both girls nodded. “I think she’ll be a pain in the ass for a while, though,” Allie said. “Like Natividad says, she’ll steal. She won’t be able to stop herself. We’ll have to watch her real good. That little kid will steal too. Steal and run like hell.”

Zahra grinned. “Reminds me of me at that age.

They’ll both be pains in the ass. I vote we try them. If they have manners or if they can learn manners, we keep them. If they’re too stupid to learn, we throw them out.”

I looked at Travis and Harry, standing together.

“What do you guys say?”

“The next one might.” I leaned toward her. “The world is full of crazy, dangerous people. We see signs of that every day. If we don’t watch out for ourselves, they will rob us, kill us, and maybe eat us.

It’s a world gone to hell, Jill, and we’ve only got each other to keep it off us.”

Sullen silence.

I reached out and took her hand. “Jill.”

“It wasn’t my fault!” she said. “You can’t prove I— ”

“Jill!”

She shut up and stared at me.

“Listen, no one is going to beat you up, for heaven sake, but you did something wrong, something dangerous. You know you did.”

“So what do you want her to do?” Allie demanded.

“Get on her knees and say she’s sorry?”

“I want her to love her own life and yours enough not to be careless. That’s what I want. That’s what you should want, now more than ever. Jill?”

Jill closed her eyes. “Oh shit!” she said. And then, “All right, all right! I didn’t see them. I really didn’t. I’ll watch better. No one else will get by me.”

I clasped her hand for a moment longer, then let it go. “Okay. Let’s get out of here. Let’s collect that scared woman and her scared little kid and get out of here.”

The two scared people turned out to be the most racially mixed that I had ever met. Here’s their story, put together from the fragments they told us during the day and tonight. The woman had a Japanese father, a black mother, and a Mexican husband, all dead. Only she and her daughter are left. Her name is Emery Tanaka Solis. Her daughter is Tori Solis.

Tori is nine years old, not seven as I had guessed. I suspect she has rarely had enough to eat in her life.

She’s tiny, quick, quiet, and hungry-eyed. She hid bits of food in her filthy rags until we made her a new dress from one of Bankole’s shirts. Then she hid food in that. Although Tori is nine, her mother is only 23. At 13, Emery married a much older man who promised to take care of her. Her father was already dead, killed in someone else’s gunfight. Her mother was sick, and dying of tuberculosis. The mother pushed Emery into marriage to save her from victimization and starvation in the streets.

Up to that point, the situation was dreary, but normal. Emery had three children over the next three years— a daughter and two sons. She and her husband did farm work in trade for food, shelter, and hand-me-downs. Then the farm was sold to a big agribusiness conglomerate, and the workers fell into new hands. Wages were paid, but in company scrip, not in cash. Rent was charged for the workers’

shacks. Workers had to pay for food, for clothing-new or used— for everything they needed, and, of course they could only spend their company notes at the company store. Wages— surprise!— were never quite enough to pay the bills. According to new laws that might or might not exist, people were not permitted to leave an employer to whom they owed money. They were obligated to work off the debt either as quasi-indentured people or as convicts.

That is, if they refused to work, they could be arrested, jailed, and in the end, handed over to their employers.

.

Either way, such debt slaves could be forced to work longer hours for less pay, could be “disciplined” if they failed to meet their quotas, could be traded and sold with or without their consent, with or without their families, to distant employers who had temporary or permanent need of them. Worse, children could be forced to work off the debt of their parents if the parents died, became disabled, or escaped.

Emery’s husband sickened and died. There was no doctor, no medicine beyond a few expensive over-the-counter preparations and the herbs that the workers grew in their tiny gardens. Jorge Francisco Solis died in fever and pain on the earthen floor of his shack without ever seeing a doctor. Bankole said it sounded as though he died of peritonitis brought on by untreated appendicitis. Such a simple thing.

But then, there’s nothing more replaceable than unskilled labor.

Emery and her children became responsible for the Solis debt. Accepting this, Emery worked and endured until one day, without warning, her sons were taken away. They were one and two years younger than her daughter, and too young to be without both their parents. Yet they were taken.

Emery was not asked to part with them, nor was she told what would be done with them. She had terrible suspicions when she recovered from the drug she had been given to “quiet her down.” She cried and demanded the return of her sons and would not work again until her masters threatened to take her daughter as well.

She decided then to run away, to take her daughter and brave the roads with their thieves, rapists, and cannibals. They had nothing for anyone to steal, and rape wasn’t something they could escape by remaining slaves. As for the cannibals…well, perhaps they were only fantasies— lies intended to frighten slaves into accepting their lot.

“There are cannibals,” I told her as we ate that night.

“We’ve seen them. I think, though, that they’re scavengers, not killers. They take advantage of road kills, that kind of thing.”

“Scavengers kill,” Emery said. “If you get hurt or if you look sick, they come after you.”

I nodded, and she went on with her story. Late one night, she and Tori slipped out past the armed guards and electrified fences, the sound and motion detectors and the dogs. Both knew how to be quiet, how to fade from cover to cover, how to lie still for hours. Both were very fast. Slaves learned things like that— the ones who lived did. Emery and Tori must have been very lucky.

Emery had some notion of finding her sons and getting them back, but she had no idea where they had been taken. They had been driven away in a truck; she knew that much. But she didn’t know even which way the truck turned when it reached the highway. Her parents had taught her to read and write, but she had seen no writing about her sons.

She had to admit after a while that all she could do was save her daughter.

Living on wild plants and whatever they could “find”

or beg, they drifted north. That was the way Emery said it: they found things. Well, if I were in her place, I would have found a few things, too.

A gang fight drove her to us. Gangs are always a special danger in cities. If you keep to the road while you’re in individual gang territories, you might escape their attentions. We have so far. But the overgrown park land where we camped last night was, according to Emery, in dispute. Two gangs shot at each other and called insults and accusations back and forth. Now and then they stopped to shoot at passing trucks. During one of these intervals, Emery and Tori who had camped close to the roadside had slipped away.

“One group was coming closer to us,” Emery said.

“They would shoot and run. When they ran, they got closer. We had to get away. We couldn’t let them hear us or see us. We found your clearing, but we didn’t see you. You know how to hide.”

That, I suppose was a compliment. We try to disappear into the scenery when that’s possible.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Parable of the Sower»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Parable of the Sower» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Parable of the Sower» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.