Holmes turned back to the fireplace. “And I cannot imagine the codex will mind. For it is better to lose a few pages than to lose one’s soul.”

Watson took the chair next to Holmes. “For a man who has just solved an extremely unusual case, you seem rather down. You must not hold yourself responsible for the death of the priest.”

“When Father Twitchell hurled himself from the tower, I plunged with him … into the depths of despair.”

“But why, Holmes?”

“You were planning to ask me how the windows were shattered. No,” Holmes smirked, “it was not one of my little experiments taken flight. When I burned that remaining evil signature an astonishing phenomenon occurred.” He closed the collar of his dressing gown and hugged himself. “A black plume billowed from the fireplace. It was not smoke, but rather something more solid, something slick and oily in appearance. It behaved like a giant snake. I now wonder if it was not similar to the material referred to among spiritualists as ectoplasm .”

“That’s incredible!”

“Yes, but I have had the misfortune of seeing it.”

Holmes walked to one of the shattered windows. Below him, Baker Street clattered and hummed with the activities of London life; a confusion of men and women, carriages and horses, all bustling to and fro across the soot-grey cobbles. “The damned thing bifurcated before exiting through these closed windows.”

“You’ve grown pale,” said Watson.

“I have a strong constitution, but I admit the sight of it has unnerved me.”

“You have clearly had a shocking experience. Come and sit down. I will ask Mrs. Hudson to bring up some breakfast.”

“Not just yet. There is something I wish to say first.”

Holmes went back to the fireplace and dropped into his armchair. “A significant part of me plunged with that accursed tome … and was dashed against the pavement below: a bit of my philosophy, perhaps; certainly my spirits. Remember the horrible depression through which I suffered in the Spring of ‘87?”

“We came through it.”

“I feel there are even blacker depths waiting to engulf me now. Which is why I am going away.”

“Going away, Holmes?”

“These last few days I have witnessed many strange things — otherworldly phenomena which I cannot explain.” He shuddered. “I have come to realize there is a significant tear in my logic. I must set myself to mending this tear before the entire fabric of my reason is rent asunder. To accomplish this I need time to think. I need a change of scenery; as cozy and as safe as they are, I feel the need to temporarily escape the confines of these rooms.”

“But where will you go?”

“The Continent,” said Holmes, gazing at the mezzotint hanging above the mantel: a reproduction of the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland. He seemed to lapse into deep thought.

“Perhaps Tibet,” he said at length, “to visit the Dalai Lama.”

“But what of your work?”

“I have always felt it my duty to use my unusual talents for the public good, and in all the years you have known me, and before then, I have never forsaken that responsibility. But now…” He shrugged. “I am in need of a very long holiday.”

“And what of all the people who have come to rely upon you? What will I tell them when they come calling and learn that their champion has disappeared, leaving them with no one to whom they can turn? That you are on holiday? Sightseeing? They will never understand.”

“Tell them whatever you wish.” Holmes grunted. “Tell them I am dead, for all I care.”

“I am not very good at fabricating lies!”

“Come now, Watson!” laughed Holmes. “You underestimate your abilities as a fabulist. You have yet to chronicle a single case of mine where you have not played fast and loose with the facts.”

The following day, after leaving Victoria Station where he had seen Holmes off to the Continent, Watson returned to Baker Street to contemplate those empty rooms. Later, while a glazier set about repairing the shattered windows, Watson sat at his friend’s desk and started writing what he felt might very well be the last story in which he would ever record the singular gifts that had distinguished the best and wisest man he had ever known.

* * * * *

TOM ENGLISH is an environmental chemist for a US defense contractor. As therapy he runs Dead Letter Press and writes curious tales of the supernatural. His recent fiction can be found in the anthology Dead Souls (edited by Mark Deniz for Morrigan Books) and issues of All Hallows (The Journal of the Ghost Story Society). He also edited Bound for Evil, a 2008 Shirley Jackson Award finalist for Best Anthology, featuring stories about strange, often deadly books. Tom resides with his wife, Wilma, and their Sheltie, Misty, deep in the woods of New Kent, Virginia.

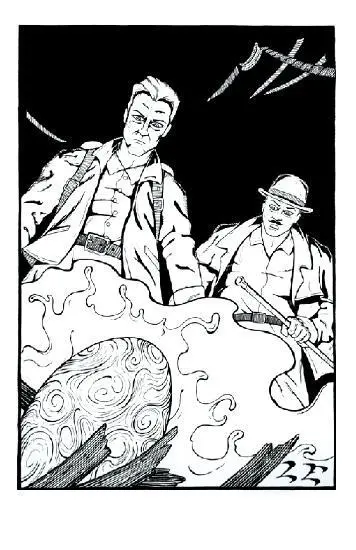

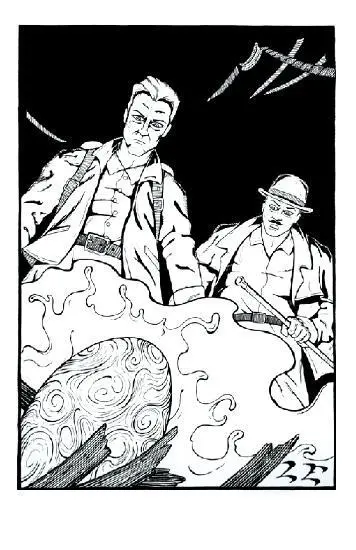

“The Color That Came To Chiswick” by William Meikle

Illustration by Luke Eidenschink

The Color That Came To Chiswick

by William Meikle

I hoped that my friend Sherlock Holmes would be more settled when I called on him that evening in May of ‘87. His recovery from his travails in France, and the subsequent excitement in Reigate, meant that a period of house rest was prescribed. As ever, he paid little attention to my ministrations and pleadings, and over the course of the previous fortnight had driven poor Mrs. Hudson to despair with a series of petty requests.

On my last visit she had pleaded with me to do my best to calm my patient . Indeed, she had worked herself into such a state that I do believe had any longer time passed it would have been her, and not Holmes, who would be coming under my ministrations.

It was Holmes himself who greeted me as I entered the house in Baker Street.

“Come in Doctor Watson,” he said in a near perfect impression of Mrs. Hudson’s Scots brogue. “You’ll be wanting some tea?”

He laughed, and fair bounded up the stairs to his apartment. I had not seen him in such good humour for several months.

I discovered why on entering his rooms … he had a new case. Several sheaves of paper lay scattered on his desk, his brass microscope was in use off to one side, and a glass retort bubbled and seethed above a paraffin burner. An acrid odor hung in the air, thick, almost chewable. The whole place reeked of it, despite the fact that the windows were all open to their fullest extent.

Holmes noticed my discomfort.

“It is nothing,” he said.

“I doubt Mrs. Hudson will agree,” I said.

“Do not worry Watson,” Holmes said. “Our esteemed landlady has gone to Earls Court with the widow Murray.”

“The Wild West show? Yes, I have seen the posters around town. It is said it will be a great spectacle.”

I had wished to inquire as to Holmes’ opinion on the authenticity of Mr. Cody’s show, but it was obvious that his mind was already elsewhere. He stood over the microscope, studying the slide contents intently.

“What have you got there Holmes?”

In answer he passed me a sheet of paper.

“This came in several hours ago.”

It was a note on letter-headed paper, from the Fullers Brewery in Chiswick, and addressed to Sherlock Holmes, Consulting Detective at this Baker Street address. The note proved to be short and to the point.

“Dear Mr. Holmes,” it began. “In the past three days we have encountered several problems with our brewing processes in our main Tuns. We suspect sabotage, but are unable to prove the cause, and our own chemists have drawn a blank. I have sent a sample from our latest fermentation, and would appreciate some of your time in its study. I shall be happy to discuss your remuneration by return of post.”

Читать дальше