Mas clenched his hands in frustration. ‘What the devil is going on over there? What is Miranda playing at?’

‘Send a boat across,’ La Valette ordered. ‘I want a report at once.’

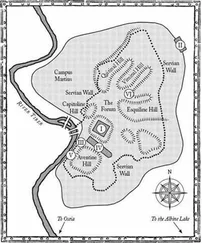

‘Yes, sir,’ Mas nodded and hurried out of the study. The others continued to watch in growing despair as the enemy emerged from the ditch all along the front of the wall and began to plant their scaling ladders against the scarred exterior of the fort. Sunlight glittered off the armour and weapons of the men defending the parapet until flame and smoke obscured the view. Then only the fierce burst of incendiaries and the swirling blaze of fire hoops were briefly visible through the smoke and dust cloaking the fort.

Below, in the deep blue water of the harbour, Thomas saw a boat striking out across the light swell towards the small landing stage below the fort. The Maltese oarsmen rowed strongly and the boat surged forward. It was over halfway across the placid expanse of water before it drew the attention of the Turks. A handful of Janissary snipers turned their long barrels from the fort and trained them on the boat. Small spurts of water erupted in the sea ahead and to the side of the boat. Those watching from St Angelo shouted their encouragement and willed their comrades on. The enemy’s shots grew more accurate as the boat neared the opposite shore. Then one struck the prow of the boat and splinters burst into the air. An oarsman clasped his arm and his oar blade dropped, dragging the boat round until the man on the tiller corrected the course and bellowed at the injured man to take up his oar. Miraculously the small craft passed out of sight of the snipers as it drew close to the landing at the foot of a low cliff. The rowers slumped over their oars as the officer Mas had ordered to report on the attack clambered from the bows and raced up the steps cut into the rock and made for the entrance at the rear of the fort, close to the cavalier tower.

The small drama was over and Thomas puffed his cheeks in relief. La Valette ordered his advisers to follow him and led them out of the study and up on to the tower above the keep from where they would have a better view of the attack on St Elmo. The sun climbed into the sky and a breeze blew in from the north, thinning the dense bank of smoke that clung to the front of the fort. As it cleared, the dreadful struggle for the ravelin and the walls was revealed. Bodies lay heaped in front of the wall, mingled with the wreckage of destroyed ladders. On the walls, more bodies were slumped on the parapet and crimson streaks ran down the pitted stonework. Above the carnage the standard of the Order still flew and the distant figures of the knights gleamed as they urged their men on, defying the enemy as they stood in clear view of the snipers firing from the shelter of their trenches, even though they risked hitting their own men.

Stokely wiped the sweat from his brow and shook his head in wonder. ‘How much longer can the Turks endure such punishment?’

‘Let them come,’ La Valette replied in a cold voice. ‘The more men they lose in taking St Elmo, the fewer we shall have to face when they attack Senglea and Birgu. And their morale will have taken a beating as well.’

The words might have been calculating and ruthless, thought Thomas, but the Grand Master was speaking the truth. As long as St Elmo held out, the Turks would throw men against the defences and suffer appalling losses as a result. In between assaults their cannon would use up precious powder and shot from the supplies they had brought with them from Istanbul. Most important of all, Thomas reflected, they would be wasting precious days of the campaign season. When the rain and storms of autumn arrived, there would be little chance of supplies and reinforcements reaching the Turks.

At last, as the bells of the churches in Birgu announced midday, the enemy attack finally began to peter out. They fell back from the walls to their trenches, leavijig the ground before the fort carpeted with the bodies of their comrades. The ravelin, however, remained in their hands and the Turkish engineers already seemed to be improving its defences by building up the height. As the last of the enemy withdrew, the guns on the ridge opened fire once more, pounding the defences. Along the walls the defenders disappeared from view as they scurried back into cover.

La Valette turned away from the grisly spectacle and Thomas saw that he looked weary, and yet there was the same unyielding determination in his eyes as he met Thomas’s gaze. ‘Thanks be to God. We have won ourselves another day.’

At midday Thomas took Richard to one side as they ate a quick lunch of bread and cheese, washed down by a sharp, vinegary local wine. Thomas quietly related what had been discussed at the morning meeting. Richard listened in silence.

‘At least you have what you came for,’ Thomas concluded. ‘I trust that it is worth risking our lives for.’

‘Taking such risks is in the nature of the game,’ Richard replied. ‘That is why you are not fit for the work that I do.’

Thomas shook his head sadly. ‘And it is why you are not fit to serve as a knight, Richard. Such skulduggery is not honourable.’

‘Really? You knights kill for your cause, and I do what I must for my country. Would you care to explain - justify - which is the more ethical path?’ He gave Thomas a searching look and then smiled thinly. ‘I thought not.’

Thomas looked at him with the frustration of one who knows he is in the right but is too weary to explain the matter. For some reason he felt an obligation to guide Richard, as if he was a real squire, or an errant son. At length Thomas sighed. ‘I trust that you have put your prize somewhere safe.’

‘It’s as well hidden as I can manage under the circumstances.’

‘Good. Then your mission is all but complete. All that remains is to survive the siege,’ he added with an ironic smile. ‘Let us bend our efforts towards rendering good service to La Valette and the Order. Until the siege is over, I serve the Grand Master only, and you serve as my squire and set aside your obedience to Walsingham and his schemes. Agreed?’

Richard thought for a moment and nodded. ‘Until the siege is over.’

The young man turned his attention back to his food, bit off a chunk of cheese and chewed hard as he gazed across the harbour towards St Elmo.

Dusk was settling over the island by the time the officer Colonel Mas had sent to St Elmo returned to make his report. He entered the Grand Master’s study and stood before the table, a bloodied dressing tied about his head. It took a moment before Thomas recognised him as Fadrique, the son of Don Garcia. They exchanged a brief nod of recognition.

‘Do you want a chair?’ La Valette asked him.

‘No, sir.’ Fadrique drew himself up proudly. ‘I will stand.’

‘Very well then. Make your report. What happened at the ravelin?’

‘Captain Miranda is not certain, sir. It seems that one of the sentries on duty in the ravelin was shot dead by a sniper. The men on duty on the exposed parts of the wall have taken to lying flat in order not to present the enemy with a clear target. This morning, it appears that the dead man’s comrades assumed he was alive and keeping watch. That was why the Turks were able to put a ladder up against his section of the ravelin and get a party of Janissaries on to it before our men were aware of the danger. By the time they reacted, it was too late and the ravelin was seized by the Turks.’

‘That is damned careless,’ Colonel Mas said bitterly. ‘Did Miranda attempt to recapture it?’

‘Yes, sir. Twice. The second time I joined the counter-attack. The Turks had fortified the ravelin and packed it full of their men. They shot us down as we tried to force our way back inside. We lost three knights and several men before we even reached the ravelin. Then it was hand-to-hand. Captain Miranda managed to get inside with three men, but was forced back and obliged to retreat into the fort.’

Читать дальше