After supper, Lin Chung escorted her to the head of the staircase where she detained him with a hand on his arm.

‘Thank you for your support tonight,’ she said. ‘You drive very well.’

The bronze face inclined gravely. ‘It was my pleasure, Silver Lady.’

‘Do you know where my room is?’

‘Yes, but I shall deny myself that honour.’

‘Oh?’ Phryne could not believe her ears. ‘Why?’

‘Your reputation, Phryne. I overheard Mr Reynolds just now. An affair with a Chinese is social ruin, he said. He is probably correct. While that remains the case, I would do nothing to injure you.’

‘Hmm.’ Phryne did not have an immediate counter-argument. This needed thinking about and she was tired and worried by Tom’s refusal to take the attack on his employee seriously. ‘Very well. I’ll see you at breakfast. Sleep well.’

‘Ah, Silver Lady,’ he whispered, so that she could only hear him by standing close, ‘not as well as I would with you.’

Phryne breathed in the cool scent of his skin for a moment, then kissed him decorously on the cheek and walked to her room, without looking back.

CHAPTER TWO

We were hinted by the occasion, not catched the

opportunity to write of old things, or intrude upon

the antiquary. We are coldly drawn unto the

discourses of antiquities, who have scarce time to

comprehend new things, or make out learned

novelties.

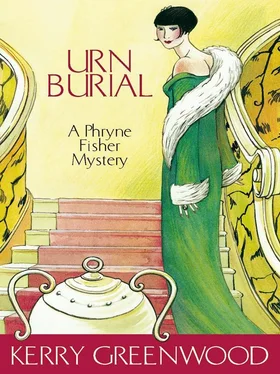

Epistle Dedicatory, Urn Burial , Sir Thomas Browne.

BREAKFAST WAS early; Phryne arrived at nine o’clock and found that most of the guests had eaten and gone. This was all to the good. She had slept well but alone, and that never improved her temper. She had only one companion: a youngish man with a very self-conscious tie and long straight dark-brown hair falling over his face, who was eating as though he did not expect to ever see bacon and eggs again – the famous surrealist poet, Tadeusz Lodz, whom she recognised at once. He was good-looking in an unwashed bohemian fashion, and as soon as he saw her he laid down his cutlery, rose to his feet and bowed over her hand, which Phryne thought was courtly above the call of duty, considering how hungry he evidently was.

She poured herself a cup of coffee and gathered some toast and a poached egg from the steaming silver dishes lined up on the buffet. The coffee was cold and she rang a small silver bell for more.

A scrubbed and bouncing housemaid, cap askew, took the order and came back in a very short time with a fresh pot. Phryne drank some of the inky beverage. It was scalding and mostly composed of chicory. She grimaced. There seemed to be some sort of idea amongst Australian cooks, amounting to a religious conviction, that the combination of lukewarm water and Grocer’s Best Ground constituted the drink which Parisians called café and wrote songs about. The poet cleared his plate, took a gulp of tea and said, ‘I am delighted to meet you, Madame. Would you care for some ham – some bacon – more toast?’

His voice was delightful, a dark-brown toffee-coloured voice, with a marked accent which turned his W into a V and made his vowels lush and prolonged.

‘No, nothing more, thank you. Well, perhaps a sliver of ham. Mr Lodz, may I ask you a strange question?’

‘Madame?’ incongruously blue eyes lit with interest.

‘Did you hear a shot last night?’

‘Do you know, the whole time I have been in this Australia, no one has asked me such a question. Remarkable. But I regret, Madame, I was struggling with some lines which would not become absurd – they remained, no matter what I did with them, ridiculously banal – and I heard nothing. Why? Who was shot?’

‘No one. A maid was attacked, though, and I certainly heard a shot.’ Phryne ate her toast. ‘Tell me, Mr Lodz, your natural habitat must be a cafe – I have never known a poet, especially a surrealist, to move far from his café au lait – what brings a town-dweller like you to the country?’

‘But who else but my host? He is to publish a small book of mine, a little volume.’ He made a dismissive gesture. ‘Nothing really, but Reynolds brought me here to finish it. If I am in the town, I have too many good companions. I drink, I talk . . . and nothing gets written. Thought, argued over, dreamed, discussed, considered, certainly – but written, no. You would know this, Madame, you who have known many poets, in Paris, perhaps? And this grotesque and delightful house is a perfect place for a surrealist – it cries out for a resident poet who can really appreciate its strangeness. Therefore, I am here. I ask the same of you. What brings so sophisticated and beautiful a lady to this rural setting, hmm?’

Phryne was wondering the same thing and enumerated her reasons over a cup of Cave House tea, which was much more palatable than the coffee.

‘Tom Reynolds is an old friend of mine, my adopted daughters are back at school, the house is empty, and I need a rest. I have just concluded a nasty case at the theatre and I felt like a little holiday.’

‘ Bien sûr ,’ agreed the poet affably. ‘Will you introduce me to your Chinese? Such a beautiful face, like a bronze. What is his name?’

‘Lin Chung. They call him Lin.’

‘I wish I could draw,’ lamented the poet. ‘Every time I see a face like that I long to be able to capture the beauty; the cool, aloof beauty in the bones.’

‘Never mind. You capture it in words.’

‘You are very kind.’ The poet smiled, revealing a face containing unexpected humour as well as the strength of character to be seen in all surrealists. It took determination to be really strange. That, or absinthe before breakfast every day.

‘So, gentle lady, a little walk, perhaps?’ He held out his arm and Phryne took it.

They walked out of the breakfast room into a pillared portico lined with enough gargoyles to trouble even a surrealist. Tadeusz winced a little and guided Phryne on to a grassy path which led into a rose garden. The fog had burned away under a cool morning sun.

‘A cigarette?’ She accepted. He opened a battered silver case which had a tarnished outline upon it resembling a rising sun. ‘They are Turkish-Balkan Sobranies which I hope are to your taste. Now, you will want to hear about the house party. You can see most of them from here.’ He escorted her to a garden seat and pointed.

‘There, playing at being civilised, is Major Luttrell – a military bully, a King Boar, I assure you, beautiful lady, along with his much-tried wife.’

She saw a tall stout gentleman leaning over a small figure under the beech tree. ‘He leads her a dog’s life,’ he said flatly. ‘Some women are saints.’

‘Which makes some men devils. If she’d climbed on a chair and flattened him with a poker when he first began to bully, he’d be a lot more amenable and might have some respect for her,’ commented Phryne.

The poet tossed back his hair and said in a faintly astonished tone, ‘As the beautiful lady says.Visible at a distance because of her illuminated gown, she has a gaudy taste, is Miss Cynthia Medenham, the novelist. You have heard of her?’

‘Yes, she writes symbolic, impenetrable prose, which if it wasn’t so hard to understand would probably be banned. But it sells well, I gather,’ said Phryne, who had given up on Silk after chapter three, despite the promising ingredients of a woman who was the reincarnation of an eighteenth-century courtesan, a tiger skin, and a virgin (but virile) boy.

‘Hmm, yes. How much of her rather lush prose arises from personal experience I cannot – alas – say.’ The poet grinned. ‘Playing with a hockey ball and stick is Miss Judith Fletcher, a jolly girl in the English manner – abominable. Do not agree to play tennis with her, she will exhaust you as she exhausted me. She drinks only water, which she calls Adam’s Ale in that intolerably hearty manner, and should marry a . . . a farmer. Instead, her mother,’ he pointed out a middle-aged lady hastening across the ground with a sunhat in her hands, ‘is determined that she should marry Gerald Randall, a flannelled fool, over there.’ Two young men were hitting a cricket ball between them in a rather desultory manner. One was slim and dark, the other tall and blond and both, indeed, were wearing flannel bags and jumpers. ‘His friend Jack Lucas is just such another – no brains at all and no appreciation of poetry. However, Mr Gerald plays the piano, passably, unless he attempts Liszt which cannot be recommended, anyway. He is absolutely passé .’

Читать дальше