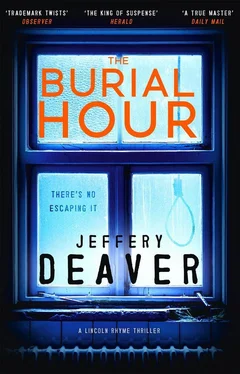

Jeffery Deaver

The Burial Hour

To the memory of my friend Giorgio Faletti.

The world misses you.

The winter wind blows and the night is dark;

Moans are heard in the linden-trees.

Through the gloom, white skeletons pass,

Running and leaping in their shrouds.

— Henri Cazalis, ‘Danse Macabre’

While the Italian law enforcement agencies I refer to in this novel are real, I do hope the fine members of these organizations, many of whom I’ve met and whose company I’ve enjoyed, will forgive the minor adjustments I’ve made to their procedures and locales, which have been necessary for the timing and plotting of the story.

And I wish to offer my particular thanks to musician and writer, translator and interpreter extraordinaire Seba Pezzani, without whose friendship, and diligence and devotion to the arts, this book could not have been written.

I

The Hangman’s Waltz

Monday, September 20

‘Mommy.’

‘In a minute.’

They trooped doggedly along the quiet street on the Upper East Side, the sun low this cool autumn morning. Red leaves, yellow leaves spiraled from sparse branches.

Mother and daughter, burdened with the baggage that children now carted to school.

In my day...

Claire was texting furiously. Her housekeeper had — wouldn’t you know it? — gotten sick, no, possibly gotten sick, on the day of the dinner party! The party. And Alan had to work late. Possibly had to work late.

As if I could ever count on him anyway.

Ding .

The response from her friend:

Sorry, Carmellas busy tnight.

Jesus. A tearful emoji accompanied the missive. Why not type the goddamn ‘o’ in ‘tonight’? Did it save you a precious millisecond? And remember apostrophes?

‘But, Mommy...’ A nine-year-old singsongy tone.

‘A minute, Morgynn. You heard me.’ Claire’s voice was a benign monotone. Not the least angry, not the least peeved or piqued. Thinking of the weekly sessions: Sitting in the chair, not lying back on the couch — the good doctor didn’t even have a couch in his office — Claire attacked her nemeses, the anger and impatience, and she had studiously worked to avoid snapping or shouting when her daughter was annoying (even when she behaved that way intentionally, which, Claire calculated, was easily one-quarter of the girl’s waking hours).

And I’m doing a damn good job of keeping a lid on it.

Reasonable. Mature. ‘A minute,’ she repeated, sensing the girl was about to speak.

Claire slowed to a stop, flipping through her phone’s address book, lost in the maelstrom of approaching disaster. It was early but the day would vanish fast and the party would be on her like a nearby Uber. Wasn’t there someone, anyone , in the borough of Manhattan who might have decent help she could borrow to wait a party? A party for ten friggin’ people! That was nothing. How hard could it be?

She debated. Her sister?

Nope. She wasn’t invited.

Sally from the club?

Nope. Out of town. And a bitch, to boot.

Morgynn had slowed and Claire was aware of her daughter turning around. Had she dropped something? Apparently so. She ran back to pick it up.

Better not be her phone. She’d already broken one. The screen had cost $187 to fix.

Honestly. Children.

Then Claire was back to scrolling, praying for waitperson salvation. Look at all these names. Need to clean out this damn contact list. Don’t know half these people. Don’t like a good chunk of the rest. Off went another beseeching message.

The child returned to her side and said firmly, ‘Mommy, look—’

‘Ssssh.’ Hissing now. But there was nothing wrong with an edge occasionally, of course, she told herself. It was a form of education. Children had to learn. Even the cutest of puppies needed collar-jerk correction from time to time.

Another ding of iPhone.

Another no.

Goddamn it.

Well, what about that woman that Terri from the office had used? Hispanic, or Latino... Latina . Whatever those people called themselves now. The cheerful woman had been the star of Terri’s daughter’s graduation party.

Claire found Terri’s number and dialed a voice call.

‘Hello?’

‘Terri! It’s Claire. How are you?’

A hesitation then Terri said, ‘Hi, there. How’re you doing?’

‘I’m—’

At which point Morgynn interrupted yet again. ‘Mommy!’

Snap. Claire spun around and glared down at the petite blonde, hair in braids, wearing a snug pink leather Armani Junior jacket. She raged, ‘I am on the phone ! Are you blind? What have I told you about that? When I’m on the phone? What is so f—’ Okay, watch the language, she told herself. Claire offered a labored smile. ‘What’s so... important , dear?’

‘I’m trying to tell you. This man back there?’ The girl nodded up the street. ‘He came up to another man and hit him or something and pushed him in the trunk.’

‘What?’

Morgynn tossed a braid, which ended in a tiny bunny clip, off her shoulder. ‘He left this on the ground and then drove away.’ She held up a cord or thin rope. What was it?

Claire gasped. In her daughter’s petite hand was a miniature hangman’s noose.

Morgynn replied, ‘ That ’s what’s so—’ She paused and her tiny lips curled into a smile of their own. ‘ Important. ’

‘Greenland.’

Lincoln Rhyme was staring out the parlor window of his Central Park West town house. Two objects were in his immediate field of vision: a complicated Hewlett-Packard gas chromatograph and, outside the large nineteenth-century window, a peregrine falcon. The predatory birds were not uncommon in the city, where prey was plentiful. It was rare, however, for them to nest so low. Rhyme, as unsentimental as any scientist could be — especially the criminal forensic scientist that he was — nonetheless took a curious comfort in the creatures’ presence. Over the years, he’d shared his abode with a number of generations of peregrines. Mom was here at the moment, a glorious thing, sumptuously feathered in brown and gray, with beak and claws that glistened like gunmetal.

A man’s calm, humorous voice filled the silence. ‘No. You and Amelia cannot go to Greenland.’

‘Why not?’ Rhyme asked Thom Reston, an edge to his tone. The slim but sturdy man had been his caregiver for about as long as the line of falcons had resided outside the old structure. A quadriplegic, Rhyme was largely paralyzed south of his shoulders, and Thom was his arms and legs and considerably more. He had been fired as often as he’d quit but here he was and, both knew in their hearts, here he would remain.

‘Because you need to go someplace romantic . Florida, California.’

‘Cliché, cliché, cliché. Might as well go to Niagara Falls.’ Rhyme scowled.

‘What’s wrong with that?’

‘I’m not even responding.’

‘What does Amelia say?’

‘She left it up to me. Which was irritating. Doesn’t she know I have better things to think about?’

‘You mentioned the Bahamas recently. You wanted to go back, you said.’

‘That was true at the time. It’s not true any longer. Can’t one change one’s mind? Hardly a crime.’

‘What’s the real reason for Greenland?’

Rhyme’s face — with its prominent nose and eyes like pistol muzzles — was predatory in its own right, much like the bird’s. ‘What do you mean by that?’

Читать дальше