"I suppose it is." Lucanus looked impressed. "It's certainly the most time-honoured. You can't buy that kind of security. And that reminds me," he went on, "speaking of buying, did you bring money?"

I turned to smile at him. "Aye, I brought money. Gold. It's in the quartermaster's wagon. Why?"

"Why not? The rest of the world still uses it, presumably, and we are going to pass through Londinium."

That sobered me. "We are indeed, Lucanus. We are indeed. I wonder what it will be like?"

He looked at me in puzzlement. "What? Londinium? Why should you wonder that? You've been there before, haven't you?"

I shook my head. "No, never. You have, I suppose?"

"Of course I have. I was there with your father, when Publius Varrus was brought there in chains by your grandfather."

"When they met Stilicho, you mean?"

"Yes."

"Luke, that was years before I was born! It has been thirty years since Stilicho went back to Rome."

"So? What does that have to do with anything, other than the compound fact that you're little more than a babe in arms and I'm not as young as I used to be?"

I shrugged. "It seems to me a lot might happen to a city in thirty years, without the Army there to keep order."

He dismissed that out of hand. "Nonsense, Caius. And anyway, the Army was there for at least a decade after Stilicho left. God, man, you're talking about the administrative centre of the Province, not some small hamlet filled with ignorant peasants. The civil authorities would have taken over immediately, when the Armies left. The curiales and the local magistracies and the Regional Councils. They were more than capable of maintaining order."

I ducked my head, conceding ignorance. "Well, you may be right, and I hope you are. But I remember what my father said about trying to enforce the law without the strength of the Army to back you up. Anyway, we'll find out in a matter of days. Three days, four at the most, if we can keep up this pace."

We had ridden forty miles that day, heading north from the Colony towards Aquae Sulis, but striking eastward at the intersection of the two main roads some thirty miles south of the town. We would spend the night here, in open meadowland beside a low-walled site that had been a march camp for centuries, and we would reach Sorviodunum, the first town on our route, by mid-afternoon. Our outward journey would take us north-east via Sorviodunum, the town the Celts called Sarum, to Silchester, then to Pontes, and on to Londinium. From there we would head straight north to Verulamium along the oldest road in all of Britain. We would return along a westerly route, by way of Alchester, Corinium and Aquae Sulis, completing a rough circle and showing our presence across the entire interior of South Britain while keeping well clear of the coastal areas where there were rumoured to be heavy concentrations of entrenched Saxons.

Lucanus put his helmet back on his head. "The lads are keen," he said, nodding down to the meadow. "They're in good spirits."

He was right. The camp was already taking shape below us, as the troopers finished stringing their harnessing lines and tethered their horses in rows, leaving enough room between animals for each rider to work unhampered by his neighbours on either side as he unsaddled his mount and looked to the animal's needs.

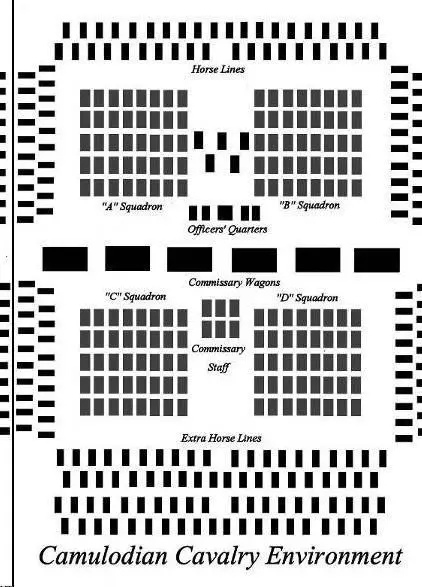

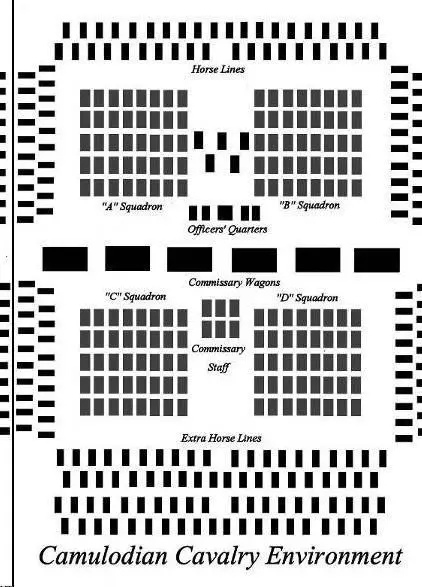

Some of the herd boys had begun to move among them, carrying bins of oats from one of the commissary wagons, while others were replenishing the water wagon's tank from the nearby brook and preparing to distribute the animals' drinking water. The remainder were attending to the tethering of the spare mounts, in the protected area directly to the south of the central crossway, closest to the road. Each horse carried its own nose-bag and leather water bucket in its saddlebags. The commissariat had been set up in the central space, equidistant from each of the four squadron encampments, with enough space surrounding it for the men to spread out and eat on the grass in comfort, if the weather was fine, or to deploy into formation around it rapidly, in the event of an emergency, without undue confusion.

I remembered the night my father had designed the layout, emphasising the need for both disciplined formality and adaptable elasticity. His original design had been for a camp of four squadrons of forty men and horses. Lesser numbers could be accommodated at individual commanders' discretion, but any force greater than three squadrons in strength could begin to present problems in disposition, dispersal and discipline.

My father's new camp formation permitted expansion to accommodate any number of squadrons, and was based on a checkerboard scheme, with the commanders quartered between the First and Second Squadrons, and the commissary staff between the Third and Fourth. I could see it clearly taking shape in the space beneath our perch on the hilltop, and I can still visualize it today. It was a shape that was famed in this land, but that has not been seen in decades and may never be seen again.

Later that night I lay awake in my cot, listening to the voices of my men, still grouped around their fires, and to the infinitely varied noises of the camp. I was pleasantly tired, but far from sleepy, and as I lay there, enjoying the comfort and the peace, my thoughts drifted through a review of everything that had happened in the past few months since the night my aunt had convinced me that Camulod should attend the Verulamian Debate in grand style.

Once convinced her advice was valid, I had not procrastinated. I thought carefully about what I had to say, and brought the results of my deliberations to the first full meeting of the Council that followed. I had argued my case eloquently, I thought at the time, and had convinced everyone of the merit of Aunt Luceiia's contentions. The vote in favour of my recommendations was unanimous, and we began making preparations immediately.

It was natural, I suppose, that everyone who heard about it, from Councillors to trainee troopers, wanted to join the excursion, but the criteria governing the expedition and its personnel were decreed absolute from the outset: this was to be a military delegation, in all of its aspects. The main objective of the exercise, apart from the obvious one of representing the concerned but cohesive and self-sufficient Christian community in the far west, was to demonstrate our military capabilities to everyone with eyes to see it. For that reason, no civilian supernumeraries would accompany the expedition. I alone would represent Camulod as Commander and spokesman. For exactly the same reason, reinforced by the solid, enlightened thinking of the Legate Titus, every trooper and every officer in the train had to earn his place.

Four brand-new, elite cavalry squadrons would be formed from the mass of Camulod's forces, and only the best in their own categories would qualify. That, we decided, was fair, since it provided the opportunity for every man, from the rawest recruit to the most seasoned veteran, to vie for a place of honour in an appropriate squadron.

Since competition among officers for the same type of honours would have been infra dignitatem, the squadron and troop commanders were selected by lot in Council and announced with much fanfare. Titus, Flavius and I myself saw to it that only the names of the very finest of our commanders were submitted, so we were sure that the chosen officers would be well received.

The competition that began immediately for inclusion in the ranks of the four squadrons did wonders for the flagging morale that had threatened us after Lot's near-capture of the fortress. Old rivalries were revived and new ones came into being overnight. The dust clouds over the great plain below the hill never settled, as squadrons and mounted troopers in twos and threes drilled, wheeled and manoeuvred at all hours until, eventually, the ranks of the new squadrons were filled and the squadron colours decided on and distributed.

Читать дальше