‘Don’t shoot unless you have to. We must conserve our powder,’ shouted Arianz from the quarterdeck. Everyone knew his meaning. The Ta-yin’s men had carried off the kegs that contained the vessel’s reserve stock of gunpowder. All the men had left was whatever they had previously transferred to their powder flasks.

‘They do not look warlike,’ observed Dan. He had joined Hector on the foredeck and was watching the approaching canoes. The Miskito’s dark eyes lit up with approval. ‘Now there is something I would like to try out at home,’ he said. ‘Those side floats are ingenious. They make their craft sit higher, and able to carry more sail, than we would among my people.’

The leading canoe had drawn level with the Nicholas . The canoe’s crew were skilfully spilling wind from the sails to slow down their craft and keep pace with the lumbering visitor. Hector saw Eaton glance farther aft. The remaining canoes were also closing the gap. Soon the Nicholas would be surrounded by a squadron of the strangers.

‘Don’t let any of them come aboard,’ the captain ordered harshly. ‘Make them keep their distance.’

The lead canoe carried four or five men, who stood and shouted.

‘What is it they are calling?’ Jacques asked.

Hector strained to hear. ‘I think they’re calling out “Hierro, hierro”, Spanish for iron.’

‘Well, at least they have a few words of a language we can understand,’ grunted the Frenchman.

One of the canoe men picked up a basket from the bottom of his craft and held it up on show.

‘He wants to trade iron for whatever he has in that basket,’ said Hector.

As usual Dan had the keenest eyesight. ‘They’ve brought out coconuts and other fruit.’

‘Mon Dieu, thank God for that,’ exclaimed Jacques. ‘I’m sick of the men complaining about mouldy salt fish and the maggots in the bread.’

Several of the Nicholas ’ men had begun waving at the other canoes to come closer, but a bellow from Eaton stopped them. ‘Wait until we have found shelter. Then we’ll trade.’

For the next half-hour the Nicholas ran on, the strange spidery canoes keeping pace with ease. The vessel cleared the southern point of the mainland and an obvious anchorage came into view, where a small island offered shelter from the northeast breeze. Slowing, the Nicholas headed for a patch of smooth water. The leadsman cried out that there were twenty fathoms of water, and her helmsman put her sails aback. Even before the anchor was let go, her escort of canoes came clustering forward.

‘Remember, allow no one aboard,’ repeated Arianz.

‘Hierro, hierro,’ the natives shouted.

‘I’ll give them hierro,’ growled a suspicious sailor. ‘Bunch of arse-naked savages.’

Not one of the islanders wore a stitch of clothing. Big, strapping men, their skins were a dark tawny colour with a very slight hint of yellow. They were taller than many on the Nicholas , and had large, square, fleshy faces. Most wore their long, black hair loose, though a few had shaven skulls and topknots. They appeared self-confident and friendly.

‘Have we any spare iron to trade with them?’ asked Jacques.

‘Only odds and ends,’ said Jezreel.

One of Eaton’s men was holding up a couple of broken links of anchor chain for the canoe men. They shook their heads and began making a circular motion with their arms.

‘What are they trying to tell us?’ asked Hector.

Dan clicked his fingers as he worked out the answer. ‘They want iron barrel hoops – most ships would carry them.’

The cooper was sent for, and he reluctantly agreed to dispose of three damaged hoops from his stores. These were waved in the air, and immediately two of the canoes shot closer.

A barter followed. Stolck leaned over the gunwale, acting as negotiator. Eventually, after much sign language and haggling, it was agreed to exchange two iron hoops for five baskets filled with fruit. Then a native on the second canoe pointed to some large gourds lying at his feet, and held up one finger.

‘What is that one trying to sell?’ asked Jacques.

‘Coconut oil, I guess,’ said Dan. The islander mimed wiping the contents of the gourds on his skin and using it to dress his hair.

‘Fresh coconut oil,’ said Jacques eagerly. ‘Let me have that. I will mash up the last of our stale bread and make fried doughboys.’

‘Make sure they don’t cheat us,’ Dan warned Stolck. ‘Get the fruit and oil on board before we part with the iron hoops.’

The two canoes sidled alongside, ropes were lowered and baskets and gourds attached. Only when these were lifted into the ship were the iron hoops relinquished. The crews of the canoes appeared to be very pleased with their trade. Their sheet-handlers tightened their lines. The men in the stern twisted their paddles to act as rudders and the canoes veered away, rapidly gaining speed as they headed back to the distant shore.

Stolck brought the first basket of fruit across to Jacques and laid it on the deck. ‘There you are, Cook. There should be plenty to go round.’ He began to lift out the coconuts. Then he swore. Underneath the top layer of fruit the basket had been filled with rubbish and gravel.

Jacques dipped a spoon into the coconut oil and licked it. ‘Delicious,’ he announced. Then he looked down at the surface of the gourd and frowned. He dipped the spoon again, tasted and spat. ‘Putain!’ he exclaimed. ‘We have been cheated. The coconut oil is only floating on the surface. The rest is sea water.’

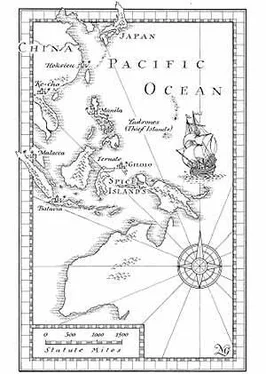

Jezreel threw back his head and gave a huge roar of laughter. ‘Well, now we know for sure that we’re at the Thief Islands.’

IT WAS A disgruntled boat crew who pulled ashore to the small island next morning in the jolly boat. Three men with loaded muskets stood guard on the beach while the rest of the shore party set about climbing the nearest coconut trees and throwing down the fruit. No natives were to be seen, though everyone had the uncomfortable feeling they were being watched. A rivulet spilled out on the beach close to the landing place, and the men dug a cistern trench so that the casks and big earthenware jars could be filled. But the supply of fresh water was little more than a trickle, and it was clear that the Nicholas would be staying several days.

For safety, most of the men stayed on board while the laborious task of watering slowly went forward. They could see many triangular sails of the native craft in the distance. But it was not until the third morning that one of the vessels was seen heading for the anchorage. It came directly to the Nicholas. This time the natives on board were not nude, but wore long, sack-like shirts made of palmetto leaves sewn crudely together. Their leader – a tall, brawny man with an impressive mop of hair – offered up a leather pouch, which was brought to Eaton. Opening it, he pulled out four sheets of paper. After a quick glance he beckoned to Hector.

‘Lynch, come over here. You can make better sense of them.’

Hector took the pages and read through them slowly. ‘All four are the same,’ he said, looking up at Eaton. ‘It’s just that they’re written in Latin, Spanish, Dutch and French.’

‘What do they say?’ asked Eaton.

Hector selected the Spanish version and read out, ‘To the commander of the unknown vessel now lying off Cocos Island. We would know your purpose in coming here. If you are Christians, you will find safe shelter at our port of Aganah. Our messenger will guide you here. Trust him, but not the Chamorro.’

‘Who are the Chamorro?’

‘They must be natives, the indios as the Spanish would call them.’

Читать дальше