Richard Pipes - The Russian Revolution

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Pipes - The Russian Revolution» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Russian Revolution

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Russian Revolution: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Russian Revolution»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Russian Revolution — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Russian Revolution», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Russia immediately violated the terms of the treaty by introducing numerous police and military units into Manchuria and establishing in Kharbin a quasi-independent base of operations. More Russian troops were sent to Manchuria during the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion (1900). In 1898 Russia extracted from China the naval base at Port Arthur on a long-term lease.

With these steps, and despite Nicholas’s desire for peaceful relations and the reservations of some ministers, Russia headed for a confrontation with Japan. In November 1902, high-ranking Russian officials held a secret conference in Yalta to discuss China’s complaints about Russia’s treaty violations and the problems caused by the reluctance of foreigners to invest in Russia’s Far Eastern ventures. It was agreed that Russia could attain her economic objectives in Manchuria only by intense colonization; but for Russians to settle there, the regime needed to tighten its hold on the area. It was the unanimous opinion of the participants, Witte included, that Russia had to annex Manchuria, or, at the very least, bring it under closer control. 24In the months that followed, the Minister of War, A. N. Kuropatkin, urged aggressive action to protect the Trans-Siberian Railroad: in his view, unless Russia was prepared to annex Manchuria she should withdraw from there. In February 1903, Nicholas agreed to annexation. 25

The Japanese, who had their own ambitions in the region, tried to forestall a conflict by agreement on spheres of influence: they would recognize Russian interests in Manchuria in return for an acknowledgment of their interests in Korea. An accord might have been reached along these lines were it not that in August 1903 Nicholas dismissed Witte as Minister of Finance: after that, Russia’s Far Eastern diplomacy began to drift, with no one in charge. It is then that socially prominent speculators, interested in exploiting Korean lumber resources, aggravated relations with Japan.* Persuaded that Russia would not negotiate, the Japanese in late 1903 decided to go to war. Although aware of Japan’s preparations, the Russians did nothing, willing to let her bear the blame for initiating hostilities. They held the Japanese in utter contempt: Alexander III had called them “monkeys who play Europeans,” and the common people joked that they would smother the makaki (macaques) with their caps.

On February 8, 1904, without declaring war, Japan attacked and laid siege to the naval base at Port Arthur. Sinking some Russian warships and bottling up the rest, they secured command of the sea which permitted them to land troops on the Korean peninsula. The battles that followed were fought on Manchurian soil, along the Korean border, far away from the centers of her population and industry, which presented Russia with considerable logistic difficulties. These were compounded by the fact that the Trans-Siberian was not yet fully operational when the war broke out because of an unfinished stretch around Lake Baikal. In every engagement, Japan displayed superior quality of command as well as better intelligence.

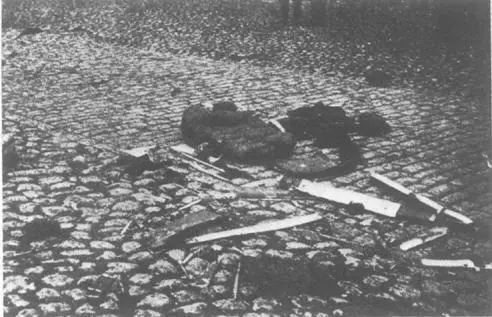

The Socialist-Revolutionary Combat Organization, which directed the party’s terrorist operations, had Plehve at the top of its list of intended victims. The minister took every conceivable precaution, but he felt confident of his ability to outwit the terrorists because he had achieved the seemingly impossible feat of placing one of his agents, Evno Azef, in the combat organization. Azef betrayed to the police an attempt on Plehve’s life, which led to the apprehension of G. A. Gershuni, the terrorist fanatic who had founded and led the group. At Gershuni’s request, Azef was named his successor. In 1903 and 1904 several more attempts were made on Plehve’s life, each of them failing for one reason or another. By then some SRs began to suspect Azef’s loyalty, and to salvage his reputation and very likely his life, Azef had to arrange for the assassination of Plehve. The operation, directed by Boris Savinkov, was successful: Plehve was blown to pieces on July 15, 1904, by a bomb thrown at his carriage.†

4. Remains of Plehve’s body after terrorist attack.

At the time of his death, Plehve was the object of universal hatred. Even liberals blamed his death not on the terrorists but on the government. Peter Struve, who at the time was editing in Germany the main liberal organ, spoke for a good deal of public opinion when he wrote immediately after the event:

The corpses of Bogolepov, Sipiagin, Bogdanovich, Bobrikov, Andreev, and von Plehve are not melodramatic whims or romantic accidents of Russian history. These corpses mark the logical development of a moribund autocracy. Russian autocracy, in the person of its last two emperors and their ministers, has stubbornly cut off and continues to cut off the country from all avenues of legal and gradual political development.… The terrible thing for the government is not the physical liquidation of the Sipiagins and von Plehves, but the public atmosphere of resentment and indignation which these bearers of authority create and which breeds in the ranks of Russian society one avenger after another.… [Plehve] thought that it was possible to have an autocracy which introduced the police into everything—an autocracy which transformed legislation, administration, scholarship, church, school, and family into police [organs]—that such an autocracy could dictate to a great nation the laws of its historical development. And the police of von Plehve were not even able to avert a bomb. What a pitiful fool!

26

Struve and other liberals would come to rue these incautious words, for it would soon become apparent that for the terrorists terrorism was a way of life, directed not only against the autocracy but also against the very “avenues of legal and gradual political development.” But in the excited atmosphere of the time, when politics turned into a spectator sport, the terrorists were widely admired as heroic champions of freedom.

Plehve’s death deeply affected Nicholas: the emotional diary entry on this event contrasts strikingly with the cold indifference with which he would record seven years later the murder of Stolypin, a statesman of incomparably greater caliber but one who happened to believe that Russia no longer could be run as an autocracy. He had lost to terrorist bombs two Ministers of the Interior in two years. Once again he stood between the alternatives of conciliation and repression. His personal inclinations always ran toward repression, and he might well have chosen another die-hard conservative were it not for the uninterrupted flow of bad news from the war front. On August 17, 1904, a numerically inferior Japanese force attacked the main Russian army near Liaoyang, forcing it to retreat to Mukden.

5. Prince P. D. Sviatopolk-Mirskii.

This happened on August 24, and the very next day Nicholas offered the Ministry of the Interior to Prince P. D. Sviatopolk-Mirskii. On the spectrum of bureaucratic politics, Mirskii stood at the opposite pole from Plehve: a man of utmost integrity and liberal temperament, he believed that Russia could be effectively governed only if state and society respected and trusted each other. The favorite word in his political vocabulary was doverie —“trust.” An officer of the General Staff who had served as governor in several provinces and as Deputy Minister of the Interior—that is, head of the police—he represented a type of enlightened bureaucrat more prevalent in late Imperial Russia than commonly thought. He completely rejected the police methods of Sipiagin and Plehve, and rather than serve under them in the Ministry of the Interior, had himself posted as governor-general to Vilno.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Russian Revolution»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Russian Revolution» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Russian Revolution» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.