Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

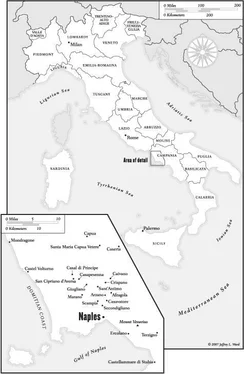

Every foot of land has its own type of trash. A dentist friend of mine once told me that a group of boys had brought him some skulls. Real human skulls. They wanted him to clean the teeth. Like so many little Hamlets, each boy held a skull in one hand and a wad of money to pay for the dental work in the other. The dentist threw them out of his office and then called me, agitated. “Where the hell do they get those skulls? Where do they find them?” He was imagining apocalyptic scenes, satanic rites, boys initiated in the language of Beelzebub. I just laughed. It wasn’t hard to figure out. I once got a flat tire passing Santa Maria Capua Vetere on my Vespa; I’d run over what looked like a sharp stick. First I thought it was a buffalo femur, but it was too small. It was a human femur. Cemeteries periodically perform exhumations, removing what younger gravediggers call the superdead, those buried for more than forty years. The cemetery directors are supposed to call specialized firms to dispose of the bodies, caskets, and everything else, down to the votive lamps. Removal is expensive, so the directors bribe the gravediggers to throw everything together on a truck: dirt, rotting caskets, and bones. Great-great-grandparents and great-grandparents, ancestors from who knows where, were piling up in the Caserta countryside. In February 2006 the Caserta NAS—the branch of the carabinieri in charge of monitoring food adulteration and protecting public health—discovered that so many dead had been dumped in Santa Maria Capua Vetere that people crossed themselves when they passed by, as if it were a cemetery. Young boys would steal the rubber gloves from their mothers’ kitchens and dig with hands and spoons for skulls and intact rib cages. Flea market vendors pay up to 100 euros for a skull with white teeth. A rib cage with all the ribs in place could bring up to 300 euros. There’s no market for shin, thigh, or arm bones; hands, yes, but they decompose easily in the soil. Skulls with blackened teeth are worth 50 euros. There’s not much of a market for them; potential buyers are not repulsed by the idea of death, apparently, but by tooth enamel that eventually starts to decay.

The clans manage to drain all sorts of things from north to south. The bishop of Nola called the south of Italy the illegal dumping ground for the rich, industrialized north. Dross from the thermal metallurgy of aluminum; smoke-abatement dust from the steel and iron industry; derivatives from thermoelectric plants and incinerators; paint dregs; liquids contaminated with heavy metals; asbestos; polluted soil from reclamation projects that then pollutes other, previously uncontaminated soil; toxic waste from old petrochemical companies such as the old Enichem of Priolo; sludge from tanning factories near Santa Croce sull’ Arno; and sediment from the purifiers of primarily publicly owned companies in Venice and Forlí.

Large companies as well as small businesses eager to rid themselves cheaply of material from which they can no longer extract anything except costs are the first step in illegal disposal. Next come the warehouse owners who shuffle the documents and collect the waste; often they dilute the toxic concentration by mixing it with regular trash, thereby registering the whole as below the toxic level set by the CER, the waste catalog of the European Community. Chemicals are essential for rebaptizing toxic waste as innocuous trash. Many operators supply false identification forms and deceptive analytic codes. Then there are the carriers who haul the waste to the selected dump site. Finally there are the people who allow for disposal: managers of authorized landfills or compost facilities where waste is turned into fertilizer, as well as owners of abandoned quarries or farmlands given over to illegal dumping. Any space with an owner can become a dump site. Fundamental to the success of the whole operation are public officials and employees who do not check or verify procedures or who allow people clearly involved in organized crime to manage quarries or landfills. The clans do not need to make blood pacts with politicians or ally themselves with political parties. All it takes is one official, one technician, one employee—one individual who wants to add to his salary. And so the business is conducted, with extreme flexibility and quiet discretion, and turns a profit for every party involved. But its architects are the stakeholders; they are the real criminal geniuses of illegal toxic-waste management. The best Italian stakeholders are shaped here, in Naples, Salerno, and Caserta. Stakeholders in business jargon are entrepreneurs who are involved in an economic project in such a way as to directly or indirectly influence its outcome. Toxic-waste stakeholders have come to constitute a regular managerial class. During the stagnant stretches of my life when I was out of work, I’d often have someone say to me, “You have a college degree and the skills, why don’t you become a stake?”

In southern Italy, at least for college graduates whose fathers are not lawyers or accountants, becoming a stakeholder is a sure path to enrichment and professional satisfaction. Educated and presentable, they study environmental policy in the United States or England for a few years and then become middlemen. I knew one. One of the first. One of the best. His name was Franco. Before listening to him and watching him work, I understood nothing of the treasure trove of trash. I met him on the train on the way back from Milan. He had graduated from the Bocconi—Italy’s most prestigious business school—and in Germany had become an expert in environmental renewal policy. One of the stakeholder’s prime skills is knowing the European Community’s waste catalog by heart and understanding how to maneuver within it, so as to work around the regulations and to find hidden shortcuts into the business community. Franco was originally from Villa Literno, and he wanted to involve me in his trade. The first thing he told me about his work was the importance of physical appearance, the dos and don’ts of the successful stakeholder. If you have a receding hairline or a bald spot, it is strictly forbidden to wear a toupee or grow your hair long to comb it across your scalp. For a winning image, you should shave your head, or at least keep your hair short. According to Franco, if a stakeholder is invited to a party, he must avoid skirt-chasing and always be accompanied by a woman. If he doesn’t have a girlfriend or a suitable date, he should hire an escort, a companion of the elegant, deluxe sort.

Stakeholders approach owners of chemical plants, tanneries, and plastics factories and show them their price list. Waste removal is an expense that no Italian businessman feels is necessary. The stakes all say exactly the same thing: “The crap they shit is worth more to them than trash, which they have to drop heaps of money to get rid of.” Stakeholders must never give the impression that they are offering a criminal service, however. They put the industrialists in touch with the clans’ trash disposers, then coordinate every step of the process from a distance.

There are two types of waste producers: those whose only objective is to save on price and who have no concern for the trustworthiness of the removal companies, considering their responsibility complete as soon as the poison leaves their premises; and those directly implicated in the operations, who illegally dispose of the waste themselves. Yet in both cases stakeholder mediation is necessary to guarantee transportation and identify a dump site, and for help in contacting the right person to declassify the waste. The stakeholder’s office is his car, and he moves hundreds of thousands of tons of waste with a phone and a portable computer. He earns a percentage on the contracts relative to the number of kilos slated for removal. His prices vary. For example, thinners, when handled by a stakeholder with ties to the clans, go for from 10 to 30 eurocents a kilo. Phosphorus sulfide is 1 euro a kilo. Street sweepings 55 cents; packaging with traces of hazardous substances, 1.40 euros; contaminated soil up to 2.30 euros; cemetery remains 15 cents; fluff, or nonmetallic car parts, 1.85 euros, transportation included. The clients’ needs and the difficulty of transport are factored into the prices. The quantities handled by stakeholders are enormous, their profit margins exponential.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.