Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It’s not hard to imagine something, not hard to picture in your mind a person or gesture, or something that doesn’t exist. It’s not even complicated to imagine your own death. It’s far more difficult to imagine the economy in all its aspects: the finances, profit percentages, negotiations, debts, and investments. There are no faces to visualize, nothing precise to fix in your mind. You may be able to picture the impact of the economy, but not its cash flows, bank accounts, individual transactions. If you try to imagine it all, you risk shutting your eyes to concentrate and racking your brains till you start seeing those psychedelic distortions painted on the backs of your eyelids.

I kept trying to construct in my mind an image of the economy, something that could convey the idea of its process and production, its buying and selling. But it was impossible to come up with a flow chart, something of precise iconic compactness. Perhaps the only way to represent the workings of the economy is to understand what it leaves behind, to follow the trail of parts that fall away, like flaking of dead skin, as it marches onward.

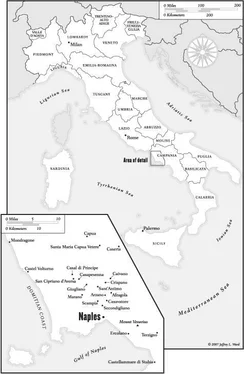

The most concrete emblem of every economic cycle is the dump. Accumulating everything that ever was, dumps are the true aftermath of consumption, something more than the mark every product leaves on the surface of the earth. The south of Italy is the end of the line for the dregs of production, useless leftovers, and toxic waste. If all the trash that, according to the Italian environmental group Legambiente, escapes official inspection were collected in one place, it would form a mountain weighing 14 million tons and rising 47,900 feet from a base of three hectares. Mont Blanc rises 15,780 feet, Everest 29,015. So this heap of unregulated and unreported waste would be the highest mountain on earth. This is how I came to imagine the DNA of the economy, its commercial transactions and profit dividends, the additions and subtractions of accountants. It is as if this mountain had exploded and scattered over the south of Italy, in particular in Campania, Sicily, Calabria, and Puglia, the regions with the greatest number of environmental crimes. These same regions head the list for the largest criminal associations, the highest unemployment rate, and the greatest number of volunteers for the military and police forces. Always the same list, eternal and immutable. In the last thirty years, the area around Caserta, between the Garigliano River and Lake Patria—the land of the Mazzoni clan—has absorbed tons of ordinary and toxic waste.

Hardest hit by the cancer of traffic in poisons are the outskirts of Naples—Giugliano, Qualiano, Villaricca, Nola, Acerra, and Marigliano—and the nearly 115 square miles comprising the towns of Grazzanise, Cancello Arnone, Santa Maria La Fossa, Castelvolturno, and Casal di Principe. On no other land in the Western world has a greater amount of toxic and nontoxic waste been illegally dumped. In the last five years the trash business has shown an overall increase of 29.8 percent, a growth comparable only to that of the cocaine market. The Camorra clans became the European leaders in waste disposal in the late 1990s; together with their middlemen, they have lined their pockets with 44 billion euros in proceeds in four years. In 2002 the parliamentary report from the minister of the interior noted a shift from rubbish collection to a pact among certain insiders in the business, aimed at exercising full control over the entire cycle. Waste management has become such big business that, despite continuous tensions, the two branches of the Casalesi clan, headed by Sandokan Schiavone and Francesco Cicciotto di Mezzanotte Bidognetti, have managed to share the vast market and avoid a head-on collision. But the Casalesi are not alone. The Mallardo clan of Giugliano distributes an immense quantity of refuse throughout its territory and swiftly apportions its revenues. An abandoned quarry in the area was discovered to be completely overflowing with trash—the equivalent of twenty-eight thousand tractor trailers. Imagine a line of trucks, bumper to bumper, that runs from Caserta all the way to Milan.

The bosses have had no qualms about saturating their towns with toxins and letting the lands that surround their estates go bad. The life of a boss is short; the power of a clan, between vendettas, arrests, killings, and life sentences, cannot last for long. To flood an area with toxic waste and circle one’s city with poisonous mountain ranges is a problem only for someone with a sense of social responsibility and a long-term concept of power. In the here and now of business, there are no negatives, only a high profit margin. Most trafficking in toxic waste runs in just one direction: north to south. Eighteen thousand tons of toxic waste from Brescia have been dumped around Naples and Caserta since the late 1990s, and a million tons ended up in Santa Maria Capua Vetere over four years. Refuse from northern treatment facilities in Milan, Pavia, and Pisa has been shipped to Campania. The public prosecutor’s offices in Naples and Santa Maria Capua Vetere, led by Donato Ceglie, discovered that in 2003 more than sixty-five hundred tons of refuse from Lombardy arrived in Trentola Ducenta near Caserta over the space of forty days.

The countrysides around Naples and Caserta are veritable maps of garbage, litmus tests of Italian industry. The destiny of countless Italian industrial products can be seen in the local landfills and quarries. I’ve always liked riding my Vespa along the dumps, on country roads that have been cemented over to facilitate truck traffic. I feel I’m moving among the remains of civilization or the strata of commercial transactions, flanking pyramids of production or the record of distances traveled; here the geography of things creates a varied and multiform mosaic. Every scrap of production, the leftovers from every activity, end up here. One day a farmer was plowing a newly purchased field on the line between Naples and Caserta when all of a sudden the tractor motor stalled, as if the earth were unusually compact in that spot. Bits of paper started sprouting up on either side of the plow. Money. Thousands, hundreds of thousands of bills. The farmer threw himself from his tractor and began frenetically collecting the loot hidden by some unknown thief, the fruit of some unknown heist. But it was merely shredded and faded scraps. Minced money from the Banca d’Italia, bales of consumed currency, now out of circulation. The temple of the lira had ended up underground, the bits of old paper currency leaching lead into a cauliflower field.

Near Villaricca the carabinieri identified a piece of land where paper towels from hundreds of dairy farms in the Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, and Lombardy had been dumped: towels used for cleaning cow udders. Farmhands have to clean the udders constantly—two, three, four times a day—every time they attach the suction cups of the automatic milker. As a result the cows often develop mastitis and similar diseases and begin to secrete pus and blood. They’re not allowed to rest, however. Their udders are simply cleaned every half hour so that the pus and blood do not get into the milk and ruin an entire can. Maybe it was just my imagination, or perhaps the heaps of yellowish udder paper distorted my senses, but they smelled like sour milk. The fact is that the trash, accumulated over decades, has reconfigured the horizons, created previously nonexistent hills, invented new odors, and suddenly restored lost mass to mountains devoured by quarries. Walking in the Campania hinterlands, one absorbs the odors of everything that industry produces. Seeing the earth mixed with the arterial, poisonous blood from an entire region of factories, I am reminded of a Play-Doh ball, the kind children make, using every available color. For decades the city of Milan’s trash was dumped near Grazzanise; all the trash collected in the city’s garbage bins or swept up each morning by the street cleaners was shipped here. Eight hundred tons of waste from the province of Milan end up in Germany every day, yet the total trash production is thirteen hundred tons. Five hundred tons are missing from official records. Where they end up is unclear, but it’s highly probable that this phantom refuse is scattered about the south of Italy. Printer toner also fouls the land, as the 2006 operation coordinated by the Santa Maria Capua Vetere public prosecutor’s office and entitled Madre Terra —Mother Earth—discovered. At night, trucks officially transporting compost or fertilizer were dumping toner from Tuscan and Lombard offices in Villa Literno, Castelvolturno, and San Tammaro. Every time it rained, a strong, acid smell blossomed: the land had become saturated with hexavalent chromium. Once inhaled, it lodges in the red blood cells and hair and causes ulcers, respiratory and kidney problems, and lung cancer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.