Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A net filled with boxes dropped jerkily from the ship’s pulley. Every time the bundle knocked against our boat, it pitched so severely that I was sure I would fall into the water. The boxes weren’t that heavy, but after stacking thirty or so in the stern, my wrists were sore and my forearms red from the corners jabbing them. Our boat took off and veered toward the coast just as two others drew up alongside the ship to collect more boxes. They hadn’t left from our jetty, but all of a sudden there they were in our wake. I felt it in the pit of my stomach every time the bow slapped the surface of the water. I rested my head against the boxes and tried to guess their contents from their smell, to make out what was inside from the sound. A sense of guilt crept over me. Who knows what I’d taken part in, without making a decision, without really choosing. It was one thing to damn myself intentionally, but instead I’d ended up unloading clandestine goods out of curiosity. For some reason one stupidly thinks a criminal act has to be more thought out, more deliberate than an innocuous one. But there’s really no difference. Actions know an elasticity that ethical judgments are ignorant of. When we got back to the jetty, the North Africans climbed out of the boat with two cartons each on their shoulders, but I had a hard enough time standing without wobbling. Xian was waiting for us on the rocks. He selected a huge carton and sliced the packing tape with a box cutter. Sneakers. Genuine athletic shoes, the most famous brands, the latest models, so new they weren’t yet for sale in Italy. Fearing a customs inspection, Xian preferred unloading them on the open sea. That way the merchandise could be put on the market without the burden of taxes, and the wholesalers wouldn’t have to pay import fees. You beat the competition on price. Same merchandise quality, but at a 4, 6, 10 percent discount. Percentages no sales rep could offer, and percentages are what make or break a store, give birth to new shopping centers, bring in guaranteed earnings and, with them, secure bank loans. Prices have to be lower. Everything has to move quickly and secretly, be squeezed into buying and selling. Unexpected oxygen for Italian and European merchants. Oxygen that enters through the port of Naples.

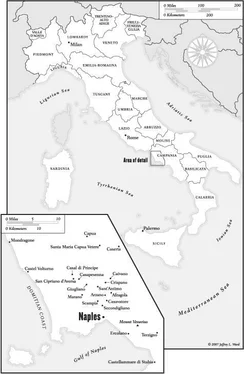

We loaded the boxes into vans as other boats docked. The vans headed toward Rome, Viterbo, Latina, Formia. Xian had us driven home.

Everything had changed in the last few years. Everything. Suddenly and unexpectedly. Some people sense the change without understanding it. Up till ten years ago, bootleggers’ boats plowed the Bay of Naples every morning, carrying dealers out to stock up on cigarettes. The streets were packed, cars were filled with cartons to be sold at corner stalls. The battles were played out among the Coast Guard, customs, and the smugglers. Tons of cigarettes in exchange for a botched arrest, or an arrest in exchange for tons of cigarettes stashed in the false bottom of a fleeing motorboat. Long nights, lookouts, whistles warning of a suspicious car, walkie-talkies ready to sound the alarm, lines of men quickly passing boxes along the shore. Cars speeding inland from the Puglia coast, or from the hinterlands to Campania. The crucial axis ran between Naples and Brindisi, the route of cheap cigarettes. Bootlegging was a booming business, the Fiat of the south, the welfare system for those the government ignored, the sole activity of twenty thousand people in Puglia and Campania. It was also what triggered the great Camorra war of the early 1980s.

The Puglia and Campania clans were smuggling cigarettes into Europe to get around government taxes. They imported thousands of crates from Montenegro every month, with a turnover of 500 million lire—roughly $330,000—on each shipment. Now all that has broken up. It’s no longer worth it for the clans to deal in contraband cigarettes. But Antoine Lavoisier’s maxim holds true: nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed. In nature, but above all in the dynamics of capitalism. Consumer goods have replaced the nicotine habit as the new contraband. A cutthroat price war is developing, as discounts mean the difference between life and death for agents, wholesalers, and merchants. Taxes, VAT, and tractor-trailer maximums are the deadwood of profit, the real obstacles hindering the circulation of merchandise and money. To take advantage of cheap labor, the big companies are shifting production to the east, to Romania or Moldavia, or even farther—to China. But that’s not enough. The merchandise is cheap, but it enters a market where more and more consumers with unstable incomes or minimal savings keep track of every cent. As unsold merchandise piles up, new items—genuine, false, semifalse, or partly real—arrive. Silently, without a trace. With less visibility than cigarettes, since there’s no illegal distribution. As if they’d never been shipped, as if they’d sprouted in the fields and been harvested by some unknown hand. Money doesn’t stink, but merchandise smells sweet. It doesn’t give off the odor of the sea it crossed or the hands that produced it, and there are no grease stains from the machinery that assembled it. Merchandise smells of itself. Its only smell comes from the shopkeeper’s counter, and its only endpoint is the buyer’s home.

We left the sea behind and headed home. The van barely gave us time to get out before it returned to the port to collect more cartons, more merchandise. I nearly fainted getting into the elevator. I took off my sweatshirt, soaked with sea and sweat, and threw myself on my bed. I don’t know how many boxes I’d carried and stacked, but I felt as if I’d unloaded shoes for half of the feet of Italy. I was exhausted, as if it were the end of a long, hard day. My apartment mates were just waking up. It was still early morning.

ANGELINA JOLIE

In the days that followed, Xian took me along to his business meetings. He seemed to enjoy my company as he went about his day or ate his lunch. I either talked too much or too little, both of which he liked. I followed how the seeds of money are sown and cultivated, how the economy’s terrain is allowed to lie fallow. We went to Las Vegas, an area to the north of Naples. Las Vegas: that’s what we call it around here, for several reasons. Just like Las Vegas, Nevada, which is built in the middle of the desert, the urban agglomerations here seem to spring up out of nothing. And you have to cross a desert of roads to reach the place. Miles of tar, wide thoroughfares that whisk you away from here, propelling you toward the highway, to Rome, straight to the north. Roads built not for cars but for trucks, not to move people but clothes, shoes, purses. As you arrive from Naples, these towns appear out of nowhere, planted in the ground one after another. Lumps of cement. Tangles of streets. A web of roads on which the towns of Casavatore, Caivano, Sant’Antimo, Melito, Arzano, Piscinola, San Pietro a Patierno, Frattamaggiore, Frattaminore, Grumo Nevano, endlessly rotate. Places so indistinguishable they seem to be one giant metropolis, with the streets of one town running into another.

I must have heard the area around Foggia called Califoggia a hundred times, the southern part of Calabria referred to as Calafrica or Saudi Calabria, Sala Consilina Sahara Consilina, or an area of Secondigliano (which means “second mile”) called Terzo Mondo, Third World. But this Las Vegas really is Las Vegas. For years, anyone who wanted to try his hand at business could do it here. Live the dream. Use his severance pay, savings, or a loan to open a factory. You’d bet on a company: if you won, you’d reap efficiency, productivity, speed, protection, and cheap labor. You’d win just the way you win by betting on red or black. If you lost, you’d be out of business in a few months. Las Vegas. No regulations, no administrative or economic planning. Shoes, clothes, and accessories were clandestinely forced onto the international market. The towns didn’t boast of this precious production; the more silently, the more secretly the goods were manufactured, the more successful they were. For years this area produced the best in Italian fashion. And thus the best in the world. But they didn’t have entrepreneurs’ clubs or training centers; they had nothing but work, nothing but their sewing machines, small factories, wrapped packages, and shipped goods. Nothing but the endless repetition of production. Everything else was superfluous. Training took place at the workbench, and a company’s quality was demonstrated by its success. No financing, no projects, no internships. In the marketplace it’s all or nothing. Win or lose. A rise in salaries has meant better houses and fancy cars. Yet this is not wealth that can be considered collective. This is plundered wealth, taken by force from someone else and carried off to your own cave. People came from all over to invest in businesses making shirts, jackets, skirts, blazers, gloves, hats, purses, and wallets for Italian, German, and French companies. Las Vegas stopped requiring permits, contracts, or proper working conditions in the 1950s, and garages, stairwells, and storerooms were transformed into factories. But lately the Chinese competition has ruined the ones producing midrange-quality merchandise. There’s no more room for workmanship. Either you do the best work the fastest or someone else will figure out how to do average work more quickly. A lot of people found themselves out of work. Factory owners were crushed by debt and usury. Many absconded.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.