Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Saviano - Gomorrah - A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But no. It’s not like that. There’s no apparent confusion. The ships all come and go in orderly fashion, or at least that’s how it looks from dry land. Yet 150,000 containers pass through here every year. Whole cities of merchandise get built on the quays, only to be hauled away. A port is measured by its speed, and every bureaucratic sluggishness, every meticulous inspection, transforms the cheetah of transport into a slow and lumbering sloth.

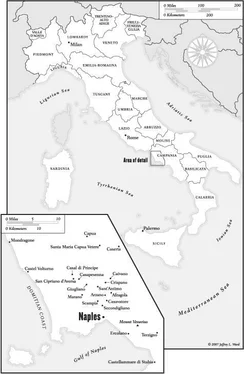

I always get lost on the pier. Bausan pier is like something made out of LEGO blocks. An immense construction that seems not so much to occupy space as to invent it. One corner looks like it’s covered with wasps’ nests. An entire wall of bastard beehives: thousands of electrical outlets that feed the “reefers,” or refrigerator containers. All the TV dinners in the world are crammed into these icy containers. At Bausan pier I feel as if I’m seeing the port of entry for all the merchandise that mankind produces, where it spends its last night before being sold. It’s like contemplating the origins of the world. The clothes young Parisians will wear for a month, the fish sticks that Brescians will eat for a year, the watches Catalans will adorn their wrists with, and the silk for every English dress for an entire season—all pass through here in a few hours. It would be interesting to read someplace not just where goods are manufactured, but the route they take to land in the hands of the buyer. Products have multiple, hybrid, and illegitimate citizenship. Half-born in the middle of China, they’re finished on the outskirts of some Slavic city, refined in northeastern Italy, packaged in Puglia or north of Tirana in Albania, and finally end up in a warehouse somewhere in Europe. No human being could ever have the rights of mobility that merchandise has. Every fragment of the journey, with its accidental and official routes, finds its fixed point in Naples. When the enormous container ships first enter the gulf and slowly approach the pier, they seem like lumbering mammoths of sheet metal and chains, the rusted sutures on their sides oozing water; but when they berth, they become nimble creatures. You’d expect these ships to carry a sizable crew, but instead they disgorge handfuls of little men who seem incapable of taming these brutes on the open ocean.

The first time I saw a Chinese vessel dock, I felt as if I were looking at the production of the whole world. I was unable to count the containers, to keep track of them all. It might seem absurd not to be able to put a number on things, but I kept losing count, the figures were too big and got mixed up in my head.

These days the merchandise unloaded in Naples is almost exclusively Chinese—1.6 million tons annually. Registered merchandise, that is. At least another million tons pass through without leaving a trace. According to the Italian Customs Agency, 60 percent of the goods arriving in Naples escape official customs inspection, 20 percent of the bills of entry go unchecked, and fifty thousand shipments are contraband, 99 percent of them from China—all for an estimated 200 million euros in evaded taxes each semester. The containers that need to disappear before being inspected are in the first row. Every container is duly numbered, but on many the numbers are identical. So one inspected container baptizes all the illegal ones with the same number. What gets unloaded on Monday can be for sale in Modena or Genoa or in the shop windows of Bonn or Munich by Thursday. Lots of merchandise on the Italian market is supposedly only in transit, but the magic of customs makes transit stationary. The grammar of merchandise has one syntax for documents and another for commerce. In April 2005, the Antifraud unit of Italian Customs, which had by chance launched four separate operations nearly simultaneously, confiscated 24,000 pairs of jeans intended for the French market; 51,000 items from Bangladesh labeled “Made in Italy”; 450,000 figurines, puppets, Barbies, and Spider-men; and another 46,000 plastic toys—for a total value of approximately 36 million euros. Just a small serving of the economy that was making its way through the port of Naples in a few hours. And from the port to the world. On it goes, all day, every day. These slices of the economy are getting bigger and bigger, becoming enormous slabs of the commercial cash cow.

The port is detached from the city. An infected appendix, never quite degenerating into peritonitis, always there in the abdomen of the coastline. A desert hemmed in by water and earth, but which seems to belong to neither land nor sea. A grounded amphibian, a marine metamorphosis. A new formation created from the dirt, garbage, and odds and ends that the tide has carried ashore over the years. Ships empty their latrines and clean their holds, dripping yellow foam into the water; motorboats and yachts, their engines belching, tidy up by tossing everything into the garbage can that is the sea. The soggy mass forms a hard crust all along the coastline. The sun kindles the mirage of water, but the surface of the sea gleams like trash bags. Black ones. The gulf looks percolated, a giant tub of sludge. The wharf with its thousands of multicolored containers seems an un-crossable border: Naples is encircled by walls of merchandise. But the walls don’t defend the city; on the contrary, it’s the city that defends the walls. Yet there are no armies of longshoremen, no romantic riffraff at the port. One imagines it full of commotion, men coming and going, scars and incomprehensible languages, a frenzy of people. Instead, the silence of a mechanized factory reigns. There doesn’t seem to be anyone around anymore, and the containers, ships, and trucks seem animated by perpetual motion. A silent swiftness.

I used to go to the port to eat fish. Not that nearness to the sea means anything in terms of the quality of the restaurant. I’d find pumice stones, sand, even boiled seaweed in my food. The clams were fished up and tossed right into the pan. A guarantee of freshness, a Russian roulette of infection. But these days, with everyone resigned to the taste of farm-raised seafood, so squid tastes like chicken, you have to take risks if you want that indefinable sea flavor. And I was willing to take the risk. In a restaurant at the port, I asked about finding a place to rent.

“I don’t know of anything, the houses around here are disappearing. The Chinese are taking them …”

A big guy, but not as big as his voice, was holding court in the center of the room. He took a look at me and shouted, “There still might be something left!”

That was all he said. After we’d both finished our lunch, we made our way down the street that runs along the port. He didn’t need to tell me to follow him. We came to the atrium of a ghostly apartment house and went up to the fourth floor, to the last remaining student apartment. They were kicking everyone out to make room for emptiness. Nothing was supposed to be left in the apartments. No cabinets, beds, paintings, bedside tables—not even walls. Only space. Space for cartons, space for enormous cardboard wardrobes, space for merchandise.

I was assigned a room of sorts. More of a cubbyhole, just big enough for a bed and a wardrobe. There was no talk of monthly rent, utility bills, or a phone hookup. He introduced me to four guys, my housemates, and that was that. They explained that this was the only apartment in the building that was still occupied and that it served as lodging for Xian, the Chinese man in charge of “the palazzi,” the buildings. There was no rent to pay, but I was expected to work in the apartment-warehouses on the weekends. I’d gone looking for a room and ended up with a job. In the morning we’d knock down walls, and in the evening we’d clean up the wreckage—chunks of cement and brick—collecting the rubble in ordinary trash bags. Knocking down a wall makes unexpected sounds, not of stones being struck but of crystal being swept off a table onto the floor. Every apartment became a storehouse devoid of walls. I still can’t figure out how the building where I worked remained standing. More than once we knowingly took out main walls. But the space was needed for the merchandise, and there’s no contest between saving walls and storing products.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.