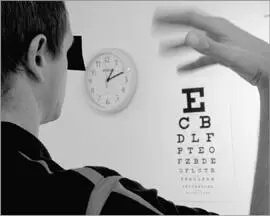

Wave to the side, above, and below your strong eye. Make sure that the strong eye does not see any letter on the chart. (If you close your weaker eye, the paper should block the central vision of your strong eye, and your strong eye would not be able to see the chart.) When you wave your hand to the side of your strong eye and you look with your weaker eye, you wake up the macula and strengthen it. This strengthens the nerve impulses and the muscles of the weaker eye, and it feels good!

Just as you did with the larger print, look at the smaller print while imagining that you are drawing the shapes of the letters. Many people then see the small print better. Look at the lowest line that you can see (which could be the third, fourth, or fifth line on the chart) as you wave your hand to the side. Now look three lines below and look at the spaces between the letters. If you cannot see the spaces between the letters three lines below, look two lines below; if you cannot see the space between the letters two lines below, look one line below. Always look below your comfort zone at spaces between the print, even though you cannot read the print. Close your eyes and say to yourself, “The ink is black and the page is white,” while imagining that your hand is waving on the other side. Saying this makes your brain engage with much smaller spaces from the distance that you can comfortably see the eye chart, whether its five, ten, or twenty feet, depending on your vision.

Figure 2.20. Put the piece of paper on the bridge of your nose to block the central vision of your strong eye.

You will then get engaged with that particular distance, and that engagement gets you to see well from that distance. Keep waving your hand on the side of your strong eye while looking at the print that you cannot really see. After looking from point to point in that print, look back at the line that you could see. Fully half of my workshop participants and private clients can see that line clearer, and some of them could even see an extra line, or a few letters of the extra line, clearer.

One particular optometrist, who attended a workshop of mine, told me this was “eye-opening” for him (no pun intended). And indeed it was. When you take the paper off, you experience that with both eyes you can see a couple of lines below the ones that you saw before, for the two maculae are working together without one suppressing the other. The effort of looking is then diminished, the desire to look increases, and the other exercises that you started to do will work better for you. When you look from a distance, you will make no effort to look at details. They will come and go; slowly and gradually, you will see more and more of them, as far as the horizon and as close as forty yards away.

Look at Details One More Time

As I said earlier, the motivation to look at details is so important. It is nice to see adults wanting to look at something trivial, something that isn’t necessary for life, like an animal walking, a beautiful garden, a sunset, or cloud formations. You can’t pay your bills with gorgeous skies, but when you look at them in a meaningful way, you’re engaging in something significant. When we were kids, we didn’t judge anything because we were not capable of earning a living then. We looked at everything out of curiosity—and, indeed, childhood vision is precious and great.

When we lose our curiosity, we lose much of our vision. Through inhibition and the requests of life, we learn to look at letters in order to gain content from them, and sometimes to see a page at a time, without looking at one single dot on that page. We observe other people only in order to understand what their expression means to us for a particular purpose or endeavor. By looking at a food shelf without paying attention to all that’s on that shelf, but just looking at the specific item that we need, we soon cut out 90 to 95 percent of the details that the world presents to us. The reason is that we know what we want way too well.

The problem is that we suppress the work of central vision and of the whole eye mechanism. The visual mechanism (the brain) does not pay attention to most details. The eye does the same thing. Many muscles get frozen: the ciliary muscles of the lens get frozen; the iris muscles of the pupils get frozen; and some of the external muscles get frozen as well, since they are not being used. Much of the retina is not working.

I will never forget a time when I saw a father and his daughter looking at some print. She was fifteen and he was in his midforties. She could see print much smaller than he could. He could see down to the fifth-print level, and she could see down to the eighth. I said to him, “At your age, you could see exactly what she sees.” After seeing hundreds of kids and how excellent their vision can be compared to the “normal” vision of adults, I could understand that childhood vision, even if it is less than normal, is much better than most adults’ vision. The father said to me, “What have I done all my life? I’ve missed out on something very important.” He had done very important things in his life: he was a surgeon, he had operated on people and saved lives, and he read books, but he did not pay attention to his own visual system; day by day, second by second, it decayed. It was clear to him and to me that if he could begin to be vigilant about his visual system and work with it, he could learn to improve his sight. Even after decreasing his visual acuity as much as he had, he was able to gain a lot of acuity that day and saw better.

In the cases of people who have lost retinal cells, renewing an interest and appreciation of details can help them gain back much of their lost vision. Your curiosity and need to look at details increases with these exercises, and you will feel more alive. You will feel that you breathe better and meditate clearer as you go along in life.

Our work, therefore, is to wake ourselves up to look at details and to revive the dormant centers in our brain. Much of the potential we possess is latent and asleep. It’s hidden from us because we adopt bad habits that we incorrectly think will work for us.

There is a continuous debate these days about vision. One side believes that simply having normal vision function is sufficient. The other side believes that paying attention to your vision function and working on it constantly is just as important as its functioning. The second group of people is still a minority, but that minority is growing. If you are reading this book and practicing the exercises, you are in the minority that believes we should always work on improving our vision. If you are in the minority, you also believe in vitalizing our vision and giving it life.

These eye exercises and those that follow can help you to see better and to feel better. Make time to do these exercises daily. The most important thing in life is to pay attention to the universe. The universe begins with you and your body. When you pay attention to your eyes, you’ll be in better contact with the whole world. You’ll also bring more circulation to your eyes, and you’ll feel better. Then you can help your own life and will find it is easier for you to help the world.

Sometimes an exercise will work perfectly fine one day, and not the same way the next day. There could be many reasons why this happens. For example, palming will work better if your shoulders are relaxed and worse if they have retained tension. Shifting will work much better if you are refreshed. Blinking (discussed in the next section) will work much better if you have a good night’s sleep and if you are relaxed at the time.

Читать дальше