The pleasure of looking at details is a form of unity with the world that nature gave us. The more we look on a regular basis, the less casual life is for us. Everything in life becomes interesting as we see all the differentiation within it.

I remember a biker who came to one of my classes in the 1980s. He rode his motorcycle from the Peninsula, a forty-minute ride to our school. After studying for two and a half hours in a vision class, he went straight to Golden Gate Park just to watch the beautiful flowers in the Arboretum, one by one. He looked at their petals and at their veins. He looked at their stems and at their leaves. Smaller and smaller details he continued to find. The class had stimulated him to want to look at beauty.

I used to ask my daughter, Adar, to go to the beach with me. I would take along an eye chart, some tennis balls, and her glasses, which had an obstruction for her left eye—it was her stronger eye—to give her right eye a chance to work more. Since she almost always resisted going, I had to tempt her by suggesting that I would put her on my shoulders. Fortunately, she remembered that she had enjoyed being on my shoulders from the time she was a baby, so she would agree. When we arrived at the beach, she would do eye exercises as she looked at the waves and into the distance. Eventually, Adar began to notice that her reading of the chart had become much better and would always say, “Daddy, why did I oppose coming to the beach? It’s just so nice to be here.”

On our way to the beach we would stop from time to time, and I’d get her to look at signs. At times, we would stop at a flowerbed right near the beach, and I’d ask her to count two hundred petals with her weak right eye. As she counted, I would look at my watch and find the count had taken between fifty-five and fifty-nine seconds. This always surprised me because it seemed too quick. I also remember another time during her adolescence, while massaging and relaxing her in a dark room, I asked, “Adar, how many petals can you count in one minute?”

She answered that she could count between thirty-five and forty.

So I said, “Adar, I have timed you and found that you can count two hundred of them in less than one minute.”

Upon that, she replied, “But, Daddy, I can’t follow my count.”

“That is the exact point,” I answered. “What happened was that you had counted automatically, and by exceeding normal speed with your counting, you engaged the macula in a function it already knows how to perform. You directed your macula to look.”

So, my daughter, whose lens was removed, and whose cornea is small, was able to exceed all expectations about her vision by connecting her brain and her macula. Everyone can do the same, either with a healthy eye or with an eye that has some defect. Like my daughter, you too can make the connection between your brain and your macula. You can move from detail to detail rapidly, and as a result your vision can become as sharp as my daughter’s vision had.

Find a lovely place to sit and look at beauty, to look from detail to detail of a beautiful thing. Once you gain this desire, the world will look beautiful to you, and you will want to mobilize yourself. It is so important that you retain curiosity about details. As children, we have it naturally; as adults, we have to make an effort to give it our attention and our souls. It is wrong to be childish, because that is immature and taxes you, but it is wonderful to be childlike, to be unfrozen and in a state of perpetual awe.

If you were born with macular degeneration or have an inclination toward it, looking at details will slow it down and may even reverse it. Looking from detail to detail is the work of the macula. Your macula becomes activated as many millions of cells start to come alive; their activity triggers activity in the brain. This activity in turn creates more synapses between the macula and the brain, and between the brain and the macula. It’s amazing how a small part of our body, the macula of the eye, can energize the whole body. It’s also important that all of us strengthen our macula so we will be able to see well for the hundred or more years that we could live.

Shifting is one of the best habits to get into.

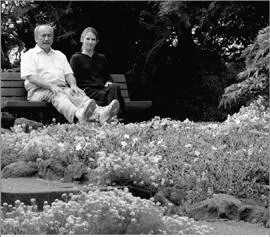

Figure 2.16. Find a lovely place to sit and look at beauty.

Read the Fine Print

People used to look at raindrops on leaves. They used to look at fruit that matured on the tops of trees. Nowadays, people tend to look just at the big picture. We learn to try and look at whole paragraphs of pages, just to grab their contents without looking at details.

In the past, we used to revere the written word. We used to read poetry. People used to look at every word and find something to respect. People used to read the same poem over and over again and find new meaning each new time they read it. Those times are over. These days, every poet who would try to live off poetry may just as well apply for welfare because there’s no way that he or she can make enough money by selling it. On the other end, suspense stories and prose with low-level content sell, and because they’re not extremely interesting when you look at them page by page, people don’t mind skimming through a whole novel to get the gist of it. This only weakens the activity of the macula. It’s the tragedy of the modern world that we don’t really engage with great presence in whatever we’re looking at.

This next exercise, therefore, is a good push in the opposite direction. Look at the page in this book with different sized paragraphs of print. Look at the third print size, which is the size of normal print.

No one has

perfect vision

all the time, and

our eyesight

varies.

Figure 2.17. Look at each letter slowly, in detail,

as if you were writing it with your mind.

Bates checked hundreds of thousands of eyes

human and animal, young and old.

While his subjects slept, ate, got sick, underwent anesthesia,

posed for photos, did arithmetic, gazed at stars, played ball, and sewed on buttons,

Bates tagged after them and measured their vision.

The results surprised him.

Bad vision got worse, got a little better, had flashes of perfect vision.

Sleep often produced worse vision.

Normal eyes went nearsighted every time the subject told a lie.

Look at each letter slowly, in detail, as if you were writing it with your mind. Follow each part of each letter with your eyes, point by point, line by line. For example, if you see a Z, you can look at the lower line of the letter; then notice the middle line, and gradually take in the top line. Look even closer to see many different points in the bottom line, many points in the middle line, and many points in the upper line. Try to distinguish between parts of the Z, even though it is just one letter. Then continue to look at all the other different letters in this same way. Look at each different part of each letter as if you were writing them slowly with dark ink

This way of looking utilizes the macula, the center of the retina, in the exact way you looked at the details in the world when you were an infant. At first, you may not have seen them well. But once you looked at whichever details you could see, you woke up the connection between the brain and the macula.

Now look at the first print size: the large print. Look from point to point on each letter in the large print. Then look back at the smaller print size and find whether you see them better than before. You can do this same exercise from two perspectives. You can start with small print and then look at larger print, or vice versa. In both ways, you should be able to reach the same results. You are training your brain to look at smaller areas than your normal tendency.

Читать дальше