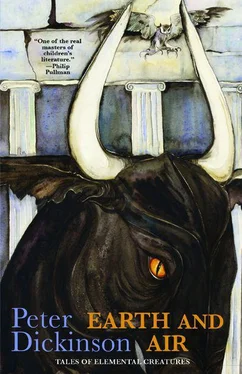

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He stopped to eat and rest in the last of their shade, looking west over the heat-hazed distances of the coastal hills. The main mass of Sunion rose on his right. It wasn’t enormous, but it was a true mountain, steep, and for half the year capped with snow that fed the fields and pastures of the valleys below. Even on this southern side the last white streaks had melted from its gullies only a few weeks back. The ridge on which he was sitting climbed towards that peak. Its crest, only fifty paces above him, had been a frontier between the homeland and enemy territory in the long, imaginary history his cousins had constructed for their wars and adventures; and in the real, everyday world that was almost true. The legal ownership of these uncultivatable uplands might be vague, but despite that the ridge was an ancient boundary, well understood by all, between Deniakis and their neighbours and dependants and those of Mentathos. Even in their wildest feats of daring, Paulo, Steff’s elder cousin, had never let any of them set foot beyond it. Now he had no choice.

An unpleasant thought came to him. He should have considered it before he ever set out. If Mentathos didn’t want anyone going into the mine to look for silver, he had probably barricaded the entrance. Well, it was too late now. Having come this far he might as well see the thing through. With a gloomy sigh he rose to his feet and started up the ridge.

He was now on a spur of the main mountain. On its eastern side it fell away even more steeply than on the side he had climbed, flanking a deep and narrow valley with the next spur beyond. At the bottom a river tumbled over a series of rapids with the remains of an old rail track running beside it.

For a while he scrambled up the ridge, mainly on the Deniakis side of the actual crest, and only when the going became too difficult, moving a few paces over onto Mentathos land. Out there he felt exposed and vulnerable, almost on the skyline in this forbidden territory. The bleak, bare valley below seemed full of hidden watchers. He reached his goal with astonishing suddenness.

There was no mistaking it. This was Tartaros. There had to be a story about such a place. It was exactly as Aunt Nix had described it.

He had found his way blocked both sides of the ridge by an immense gash slicing into the spur, clean through the crest and into the southern slope, as if the mountain had been split apart by a single, unimaginably powerful stroke. Craning over the edge he saw that the two opposing cliffs reached almost down to the level of the valley floor. There were places where it seemed obvious that one cliff must once have fitted snugly against the other. And there, at the bottom of the opposite cliff and some way to his right, lay the entrance of Tartaros. It was simply a dark hole in the vertical rock. The rail track he had seen in the valley turned up into the cleft and turned again into the opening. He could see no sign of a barrier. That settled it. He would go on.

Easier said than done. Some of the rocks that composed the plunging slope were as large as a house, and he had to find ways either down or round them. And then, when he had almost reached the bottom, a secondary cliff forced him some way back along the valley before he could at last scramble down to the river.

He started warily up the rail track. The sleepers were mostly rotten and the rails were thick with rust, but in one place a swarm of flies buzzed around a pile of recent mule droppings—yesterday’s, or the day’s before, he thought. Alarming, but only half his mind was on the obvious dangers of what he was doing. The other half was trying to decide if what he was now seeing was at all like any of the shifting landscapes of his dream. Had one of them had a rail track running beside a river? Surely he would have remembered that, but no.

He came to the cleft and turned into it, left. It had been right in the dream, hadn’t it? And of course no rail track. He’d been following Ridiki along a goat track. And those last dreadful moments, when he’d been toiling after her up the slope as she danced ahead . . . Here only a mild gradient led to the dark entrance of Tartaros.

He reached it and his heart sank. What he was looking at was no deeper than the cave on the way to Crow’s Castle. Its back wall was formed by a solid-looking timber barrier. The rail track ran on through it beneath double doors with a heavy padlock hanging across the join.

Well, it would have to do. He would find somewhere to hide or bury the collar and pipes, and then call his second farewell through a crack in the door. Gloomily he entered the cave. It wasn’t very promising. A natural cave might have had projections and fissures, but this had been shaped with stonecutters’ tools to an even surface. A small cairn then, piled into one of the far corners . . .

Without any hope at all he checked the lock, and everything changed. It was locked sure enough, but only into one of the pair of shackles, one in each door, through which it was meant to run. Somebody must have deliberately left it like that, closing the door either from inside or outside in such a way that it looked from any distance as if it were properly fastened. For instance, they might have lost the key inside the mine. Or they might be inside now. Someone had been here not long ago. Those mule droppings . . .

And the lock looked fairly new. Nothing like as old as the rails.

It didn’t make any difference. He was still going to do what he’d come for. With a thumping heart he eased the door open, first just a crack, and then far enough for him to slip through.

Darkness. Silence, apart from the drumming of his own blood. No. From somewhere ahead the rustle of moving water. He waited, listening, before closing the door and taking his hand torch out of his satchel. Shading the light with his left hand, he switched it on. Cautiously he allowed a crack of light to seep between his fingers.

The rails stretched away into the dimness along a tunnel whose walls were partly natural, partly shaped with tools. Only a few paces along, low in the right-hand wall, he made out what he was looking for, a vertical crack in the rock, as wide as his clenched fist at the bottom and tapering to a point at about knee height. Having checked, and found it was deep enough, he laid the collar and pipes ready, collected some fragments of rock to seal them in with, knelt beside the crack, and picked up the collar, and straightened.

No need to shout. If Ridiki could hear him, it would not be with earthly ears, and suppose whoever had left the door unlocked was somewhere ahead down there, he would be nearer the source of the water-noises, which should be enough to mask a quiet call from the distance.

“Good-bye, Eurydice. Good-bye, Ridiki. Be happy where you are.”

He was answered twice, first by the echo and then, drowning that out, by the bark of a dog, a sharp, triple yelp, a pause, and then the same again. And again. The alert call that every Deniakis dog was trained to give to attract its master’s attention to something he might need to be aware of. It could have been Ridiki. (No, for course it couldn’t. She was dead.) Out on the open hillside he would have known her voice from that of any other dog in Greece, but the echoing distances of the place muffled and changed it.

The call died away into uncertainty, as if the dog wasn’t sure it was doing the right thing. Steff found he had sprung to his feet, tense with mixed terror and excitement. The pipes were still on the floor where he had left them. He stuffed the collar in his pocket and picked them up, but continued to stand there, strangely dazed. Whatever the risk, it was impossible to turn away. To do so would haunt him for the rest of his days. He had to be sure. Shielding the torch so that it lit only the patch of floor immediately in front of his feet, he stole on. The daze continued. He felt as if he carried some kind of shadow of himself inside himself, its hand inside the hands that held the pipes and torch, its heart beating to the beat of his heart, its feet walking with shadow feet inside his feet of flesh and bone but making a separate soft footfall.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.