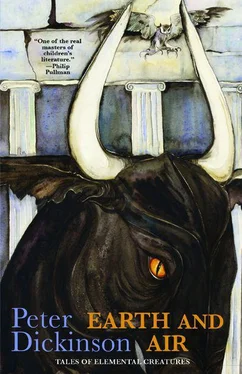

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They wrangled on, deliberately trying to keep Steff amused, he guessed. He tried to pay attention in a dazed kind of way. All he knew was that he had to go and look at the cave, if only to get rid of the dream. It couldn’t be helped that it was on Mentathos land. There’d always been bad blood between Deniakis and Mentathos, and it had been worse since the troubles after the war, when some of the young men had fought on opposite sides, and terrible things had been done. Papa Alexi made the point himself.

“Don’t you go trying it, Steff,” he said. “It’s not only Mentathos being a hard man, which he is, and he’d be pretty rough with you if you were found. He’d make serious trouble with your uncle. His father sold the mineral rights to a mining company. They came, and cleaned out any silver there was to be had. On top of that they’ve still got the rights, fifty-odd years. No wonder he’s touchy about it. Last thing he needs is anyone finding silver again.”

“Steff just wants to look,” said Aunt Nix. “It’s to do with your dream, isn’t it, Steff? Tartaros. I bet you that’s where it came from, your dream. Eurydice, after all. You remember the story, Steff . . .”

He barely listened.

Of course he knew the story, because of the name, though he hadn’t thought about it till now. Ridiki had already been named when he’d got her, so in his mind that’s who she was, and nothing to do with the old Greek nymph she was named from. But that didn’t stop Aunt Nix telling him again what a great musician Orpheus had been in the days when Apollo and Athene and the other gods still walked the earth; and how he’d invented the lyre, and the wild beasts would come out of the woods to listen enchanted to his playing; and how when his wife Eurydice had died of a snakebite he’d made his way to the gates of the underworld and with his music charmed his way past their terrible guardian, the three-head dog Cerberus, and then coaxed Charon, the surly ferryman who takes dead souls across the river Styx into Tartaros, the underworld itself; and how at last he’d stood before the throne of the god Dis, the iron-hearted lord of the dead, the one living man in all that million-peopled realm, and drawn from his lyre sounds full of sunlight, and the sap of plants and trees, and the pulse of animal hearts, and the airs of summer.

“Then Dis’s heart had softened just the weeniest bit,” said Aunt Nix, “and he told Orpheus that he’d got to go back where he belonged, but Eurydice could follow him provided he didn’t look back to make sure she was there until he stood in the sunlight, or she’d have to go back down to the underworld and he’d never see her again. So back Orpheus went, across the Styx, past the three snarling heads of Cerberus, until he saw the daylight clear ahead of him. But then he couldn’t bear it any more, not knowing whether Eurydice was really there behind him, and he looked back over his shoulder to check, and there she was, plain as plain, but he wasn’t yet out in the sunlight, and so as he turned to embrace her she gave a despairing cry and faded away into the darkness and he never saw her again.”

“I really don’t think . . .” said Uncle Alexi.

“Nonsense,” said Aunt Nix. “Steff only wants to look. He can do that from above. Like we did, Lexi. You go up the track toward the monastery and turn right at the old sheepfold, and then . . .”

Steff listened with care to her directions.

“Really, this isn’t a good idea,” said Papa Alexi when she’d finished.

“Please,” said Steff. “It’s not just I want to. I . . . I’ve got to.”

Papa Alexi looked at him and sighed.

“All right,” he said. “Start early. It’s a long way, and it’ll be hot. Take enough water. There’s a stream a little after you turn off at the sheepfold—you can refill your bottle there. You probably won’t be back till after dark. Scratch on my shutter when you’re home.”

He spent the evening writing his Sunday letter to his mother. She lived in Athens, with her new family. He didn’t blame her, or even miss her most of the time. She had a little shop selling smart, expensive clothes to rich women. That was what she’d been doing when she’d met his father, who’d worked for the government in the Foreign Ministry. Athens was where she belonged.

Steff didn’t remember his father. When he was still a baby some terrorists had tried to set off a bomb under the Foreign Minister’s car, but they’d got the wrong car, the one Steff’s father had been in, so he didn’t remember him at all. He’d no idea what he had thought about things. But he’d been a Deniakis, so Steff was pretty sure he’d felt much the same as he himself did, that he belonged on the farm.

Though he’d spent most of his first five years in Athens, his earliest memory was of sitting on a doorstep holding a squirming puppy he’d been given to cuddle and watching chickens scrattling in the sunlit dust. And then of a shattering, uncharacteristic tantrum he’d thrown on being taken out to the car to go back to Athens. He’d had a stepfather by then, Philip, and a stepsister soon after. Everyone had done their best to make him feel part of this new family, but he hadn’t been interested. Time in Athens was just time to be got through somehow. Two or three months there were nothing like as real for him as a few days on the farm, being let help with the animals, harvesting fallen olives, tagging round after his cousins.

By the time he was six his mother was driving him up there at the start of the school holidays, and fetching him when they were over. It had been his idea that he should live there most of the time, going to the little school in the town. She’d come up to see him for a few days at a time, fetch him to Athens for Christmas, take him on the family summer holiday. He got along all right with his steps, and was fond of his mother. She took trouble and was fun to be with. He guessed that she felt much the same as he did, a bit guilty about not minding more.

So he was surprised now to find how much he wanted to tell her about Ridiki. He’d always put something about her in his weekly letters, and she always asked, but this time everything seemed to come pouring out—what had happened, how he’d searched for her, found her, buried her, his misery and despair and utter loneliness. And the dream—Ridiki glancing over her shoulder and vanishing, and him not even being able to say good-bye. He had said good-bye to her once, in the real world, at her graveside. But if he was ever going to let go of her completely he had to do it again in the dream world where she had gone. He mustn’t keep anything. He would take her collar, and the shepherd’s pipes he’d used to train her, and find somewhere inside the cave to hide them, where they’d never be found, and call his good-byes into the darkness, and go. Then it would be over.

All this he wrote down, hardly pausing to think or rest. He fetched his supper up to his room and wrote steadily on. It was as if his mother was the one person in all the world he needed to tell. Nobody else would do. When he’d finished he hid the letter, unsealed, in his clothes-chest, got everything ready that he’d need for the morning, and went to bed, willing himself to wake when the cocks crew.

Of course he woke several times before that, certain he must have missed their calls, but he didn’t when at last they came. He stole down the stairs, put on the clothes that he’d hidden beneath them with his satchel, and left. Hero, the old watchdog, rose growling at his approach, but recognised Steff’s voice when he called her name, and lay back down. It was still more dark than light when he set out towards the monastery, making the best speed he could through the dewy dawn air.

He reached the ridge around noon. The last several miles he had sweated up goat paths under a blazing sun. But so far so good. He had started to explore these hillsides as soon as he’d been old enough to follow his cousins around, so he’d found his way without trouble among the fields and vineyards and olive groves on the lower slopes, the rough pastures above them where he, with Nikos’s help, had taught Ridiki the business of shepherding, and then, above those, up between the dense patches of scrub that was the only stuff that would grow there.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.